How Do Our Brains Recognize Faces?

- Published8 Oct 2021

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Ever lost your friend in a crowd during pre-COVID times and tried to find them amidst a sea of faces? A region in your brain called the fusiform face area may help you do so quickly and easily.

This is a video from the 2021 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

Created by Wilson Lim.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

In our daily lives, we will no doubt encounter numerous faces, be it that of your family members, housemates, or from videos or pictures. Faces provide a rich source of critical information, such as the person’s identity, their age, or their emotion. Although faces do seem quite similar, having 2 eyes, a nose, and a mouth which vary in size, shape, and color, humans are quite good at recognizing them! Otherwise, we would be terrible at social interactions!

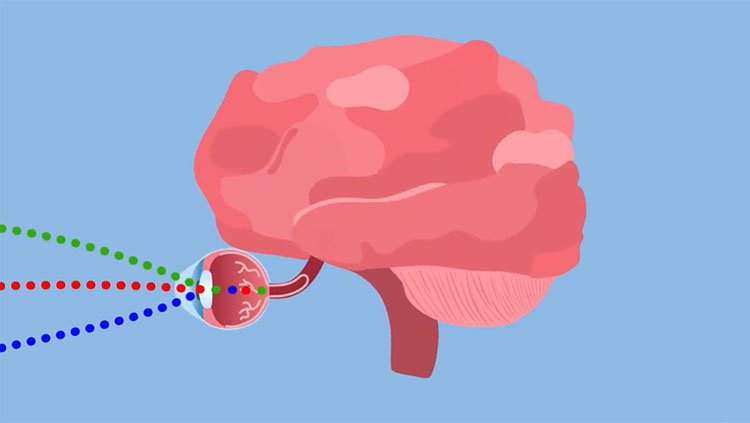

We also seem to recognize faces even when there is none. This perception of a familiar object is called pareidolia, and could explain why you might see a face in all sorts of places. So how do we recognize faces? Well, there is a specialized part of the brain located in the inferior temporal cortex, which is associated with object recognition, called the fusiform face area, or the FFA. In fMRI studies measuring brain activity, activity in the FFA was found to be the strongest when looking at faces, but not objects.

This is further illustrated by a 2012 study which examined a patient with electrodes implanted in his FFA. When the FFA was directly stimulated, his perception of faces was distorted, but not so for other objects in the room. However, there is still debate on whether the FFA is activated just because it is really good at identifying complex objects we see a lot, or is activated because it has evolved to do so when perceiving faces.

These 2 competing hypotheses are termed the expertise hypothesis and the domain specific hypothesis respectively. On one hand, evidence supporting the expertise

hypothesis include studies looking at greebles. These are novel objects created as stimuli for face recognition studies, such that participants would not have any previous experience of identifying these greebles from one another. After participants were trained to recognize and categorize the greebles, the FFA in these participants were just as strongly activated with greebles as with human faces.

On the other hand, evidence supporting the domain-specific hypothesis comes from people with prosopagnosia, or face blindness. These individuals are unable to recognize faces, whilst still being able to recognize objects. Some evidence has found that damage in the FFA seems to impair facial recognition in individuals with a variant of prosopagnosia called apperceptive prosopagnosia.

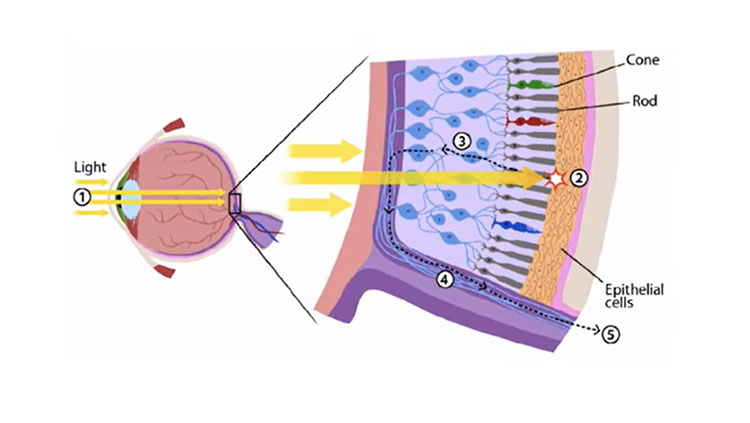

However, the role of the FFA in prosopagnosia is still being examined. It may be the case that the FFA is evolved to recognize faces specifically, but some experience with them is required to shape this selectivity. More research needs to be carried out to determine this. So, how does this brain region help you identify faces? Firstly, we need to understand how we process objects and faces. When we look at objects, we process them in a part-based fashion: we see something that is round, has numbers, and arrows, and combine them together to recognize the object as a clock.

However, when we look at a face, we process it holistically. We recognize the different facial features and are extremely sensitive to how these features are configured in relation to each other, and recognize all of them at once as a face. This configuration of facial features is important as if these features are not in their normal arrangement and orientation, there will be lower levels of FFA activation. This is seen with inverted faces, which are harder to recognize than upright faces.

The holistic processing of faces can also be illustrated through the Thatcher effect. Take a look at these 2 flipped pictures of Margaret Thatcher. It may not be obvious to you that the eyes and mouth are in their normal upright orientation in one of the pictures. However, when you flip them both back to their upright orientation, the changes are now grotesquely obvious. To conclude, although human faces may differ slightly from one another, our brain is able to recognize and identify faces quickly and easily.

So rest assured the next time when you lose your friend in a crowd, whenever that may become a thing again, you will be able to easily recognize them in the sea of faces.

Also In Vision

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org