Beyond Face Value: How Our Brains Recognize Faces

- Published1 Oct 2021

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Our knack for recognizing faces helps us communicate with those around us and learn about our environment. Distinct regions of the brain process others faces, but they have some limitations. We’re better at recognizing faces that are right-side up as opposed to upside-down. So what happens when a global pandemic forces us to cover up half of our faces?

This is a video placed second in the 2021 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

Created by Monica Tschang

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

We're really good at identifying faces. A 2018 study found that the average person can recognize up to 5,000 faces. So why are we so good at it? As social creatures, facial recognition and processing evolved as a survival mechanism. We use faces to recognize other people, identify their mood, and communicate with them. Although this developed before verbal and written language were invented, we still see the unique value of facial expressions on a daily basis when we use our smartphones. Faces also offered a way for us to get information about our surroundings from other people. We learned what to eat and what not to eat from watching others. We also learned to track other people's gaze by watching their eyes.

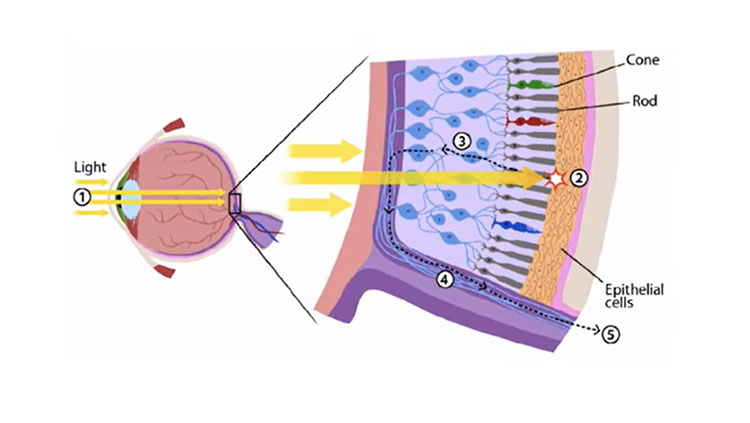

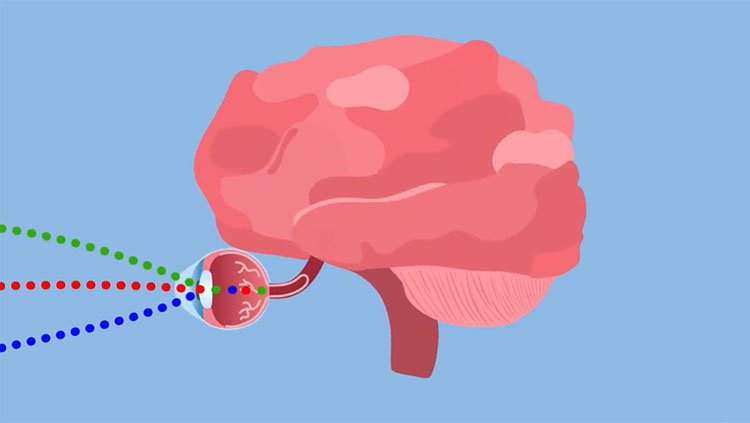

Okay, so we're good at recognizing faces but what's happening in our brains? Visual processing of faces goes through many brain areas including the fusiform face area, the occipital face area, the amygdala, and the frontal lobe.

The fusiform face area activates specifically in response to faces. This area was once thought to be the singular brain area where faces were processed and recognized. While we now know that this isn't the case, we do know that people born blind also activate this area when given sculptures of faces to touch.

The occipital face area is responsible for identifying parts of faces — for example, noses, mouths, and eyes. More recently, it has been found to be involved with higher order processing, such as identity-specific semantic memory. In other words, the OFA is in charge of associating a face to certain parts of that person's identity, like name and occupation.

The emotional evaluation part of facial recognition involves other brain regions such as the amygdala and frontal lobe. We know that these brain regions are important for facial recognition because of fMRI and brain injury studies. People with brain damage in these areas have difficulty recognizing faces, a condition known as prosopagnosia.

While our brains have the machinery to recognize faces, it does have some preferences. For example, we are much better at recognizing faces when they're upright compared to when they're upside down. This is called the inverted face effect. Behavioral studies prove this by asking one group of participants to learn new upright faces and another group to learn upside-down faces. When asked to identify the faces that they just learned, the upside-down group performed worse than the right-side up group.

We not only like right-side up faces but also whole faces. For example, it's easy to recognize that there are two distinct faces being put together here. But it takes longer to recognize the two distinct faces here because our brain is trying to make sense of the image as a whole face.

So what happens when a certain global pandemic forces us to cover half of our faces for over a year? Remember the inverted face effect? When a similar experiment is done on masked faces the decreased ability to recognize faces when they're upside down isn't as large. This suggests that face recognition with a mask on is likely through a different cognitive pathway than face recognition without a mask. This is likely because face processing with a mask can't rely on holistic approaches, so instead focuses on individual features. With vaccines becoming more accessible we are starting to fight back against the coronavirus, and, for some, masks are no longer necessary. However, masks have become a normal part of life for some people and it's likely they'll continue to be used even after the pandemic. Nevertheless, our brains are incredibly adaptable and, while seemingly inconvenient, masks may force us to look beyond face value.

Also In Vision

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org