Nightvision

- Published16 Aug 2018

- Reviewed16 Aug 2018

- Author Charlie Wood

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

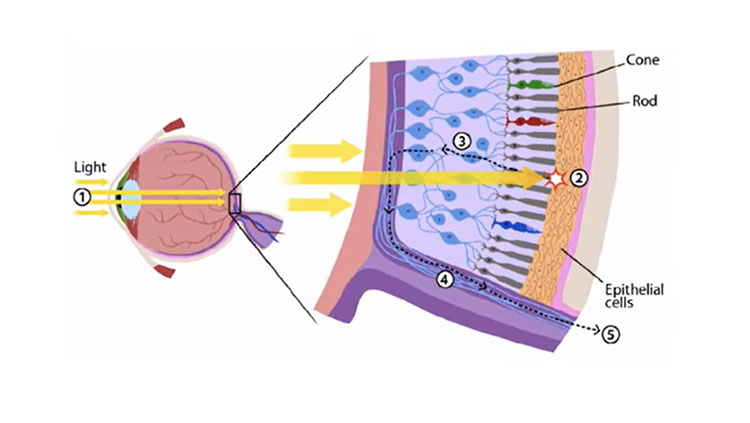

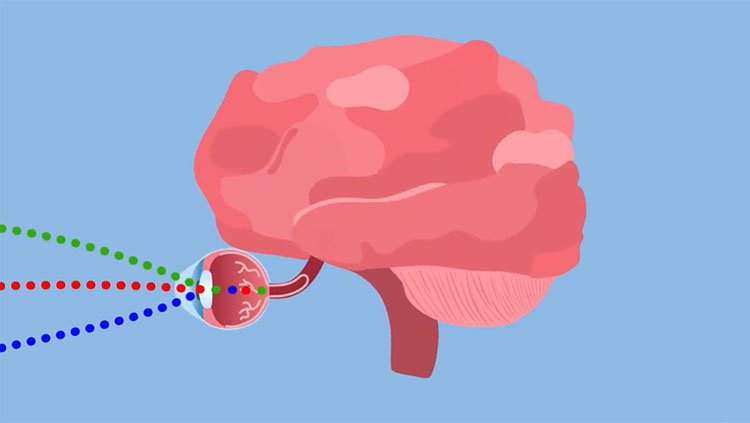

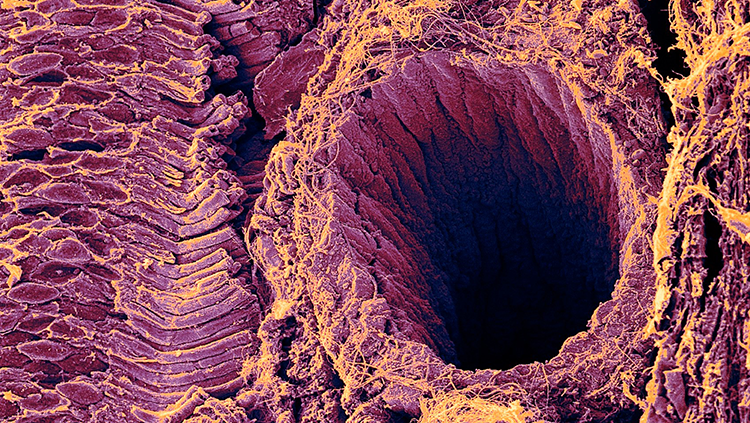

The gaping maw of the blood vessel on the right side of this image may draw the eye, but what really deserves your attention are the tightly stacked tubes on the left. Seen here in a guinea pig’s eye, these rod cells, together with their counterpart cone cells, start your sense of vision. They take in rays of light from the outside world and spit out electrical pulses for your brain to spin into images.

Working in concert, these two types of specialized neurons allow your eyes to work at all times of day. You can see by the light of the sun at noon, and also by the stars and the moon at night . In the evening or in a dark room, cones step aside and let the rods shine. One such cell can detect a single ray of light, which makes them about 100 times more sensitive than the cones. They don’t register color though, and they need longer to recharge after firing, so it can take your eyes half an hour to fully adjust to the dark — and even then you see only shades of gray.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., editors. Neuroscience. 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2001. Functional Specialization of the Rod and Cone Systems. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10850/

Spring, Kenneth R., et al. “Molecular Expressions Microscopy Primer: Physics of Light and Color - Human Vision and Color Perception.” Molecular Expressions Cell Biology: Bacteria Cell Structure, Optical Microscopy at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory., 13 Nov. 2015, 2:18, micro.magnet.fsu.edu/primer/lightandcolor/humanvisionintro.html.

Also In Vision

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org