Seeing Beyond the Visual Cortex

- Published5 Mar 2015

- Reviewed5 Mar 2015

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Research could lead to new rehabilitative therapies when the visual cortex is damaged.

It's a chilling thought —losing the sense of sight because of severe injury or damage to the brain's visual cortex. But, is it possible to train a damaged or injured brain to "see" again after such a catastrophic injury? Yes, according to Tony Ro, a neuroscientist at the City College of New York, who is artificially recreating a condition called blindsight in his lab.

"Blindsight is a condition that some patients experience after having damage to the primary visual cortex in the back of their brains. What happens in these patients is they go cortically blind, yet they can still discriminate visual information, albeit without any awareness." explains Ro.

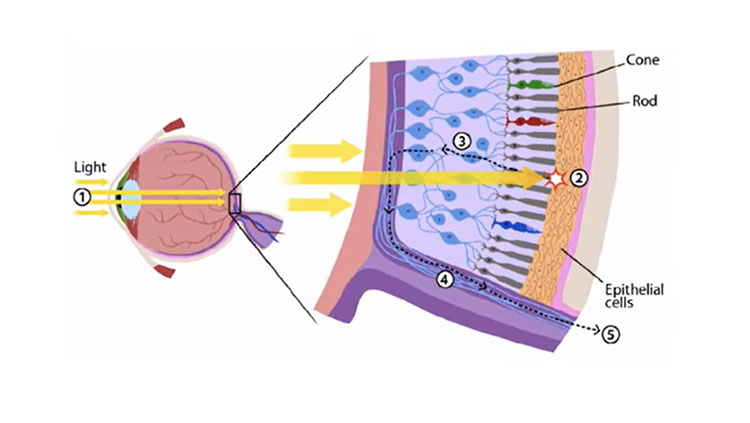

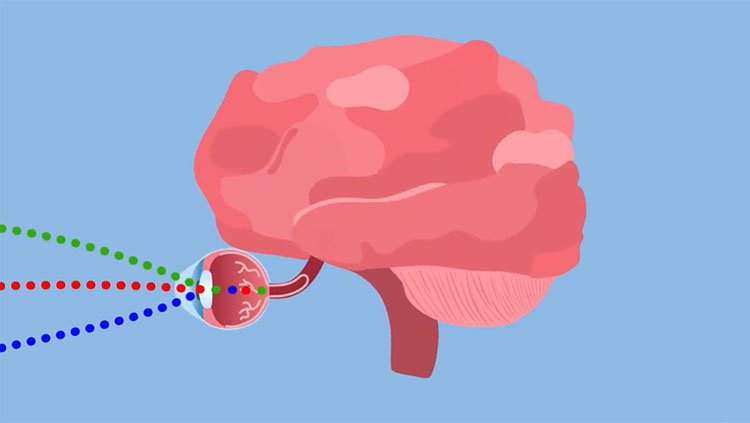

While no one is ever going to say blindsight is 20/20, Ro says it holds tantalizing clues to the architecture of the brain. "There are a lot of areas in the brain that are involved with processing visual information, but without any visual awareness." he points out. "These other parts of the brain receive input from the eyes, but they're not allowing us to access it consciously."

With support from the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences, Ro is developing a clearer picture of how other parts of the brain, besides the visual cortex, respond to visual stimuli.

In order to recreate blindsight, Ro must find a volunteer who is willing to temporarily be blinded by having a powerful magnetic pulse shot right into their visual cortex. The magnetic blast disables the visual cortex and blinds the person for a split second. "That blindness occurs very shortly and very rapidly — on the order of one twentieth of a second or so," says Ro.

On the day of Science Nation's visit to Ro's lab in the Hamilton Heights section of Manhattan, volunteer Lei Ai is seated in a small booth in front of a computer with instructions to keep his eyes on the screen. A round device is placed on the back of Ai's head. Then, the booth is filled with the sound of consistent clicks, about two seconds apart. Each click is a magnetic pulse disrupting the activity in his visual cortex, blinding him. Just as the pulse blinds him, a shape, such as a diamond or a square, flashes onto a computer screen in front of him.

Ro says that 60 to nearly 100 percent of the time, test subjects report back the shape correctly. "They'll be significantly above chance levels at discriminating those shapes, even though they're unaware of them. Sometimes they're nearly perfect at it," he adds.

Ro observes what happens to other areas of Ai's brain during the instant he is blinded and a shape is flashed on the screen. While the blindness wears off immediately with no lasting effects, according to Ro, the findings are telling. "There are likely to be a lot of alternative visual pathways that go into the brain from our eyes that process information at unconscious levels," he says.

Miles O'Brien, Science Nation Correspondent

Jon Baime, Science Nation Producer

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Vision

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org