The Neurons Responsible for Making a Touch Feel Pleasant

- Published10 Nov 2021

- Author Calli McMurray

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

A small group of neurons in the spinal cord of mice may underlie the pleasant, rewarding feelings associated with touch. Mice born without these neurons become more susceptible to the negative effects of stress. Researchers presented their work, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, at a press conference connected to the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience on November 2.

Our sense of touch profoundly affects our wellbeing. A hug from a loved one can ease the toil of a hard day, and a rub on the back soothes an upset child. “But we don't actually know how touch is experienced as pleasant,” said Melanie Schaffler, a graduate student at the Zuckerman Institute at Columbia University. “Why is a back rub different from sitting back in your chair? Both are touch sensations on your back, but they have a different emotional quality.”

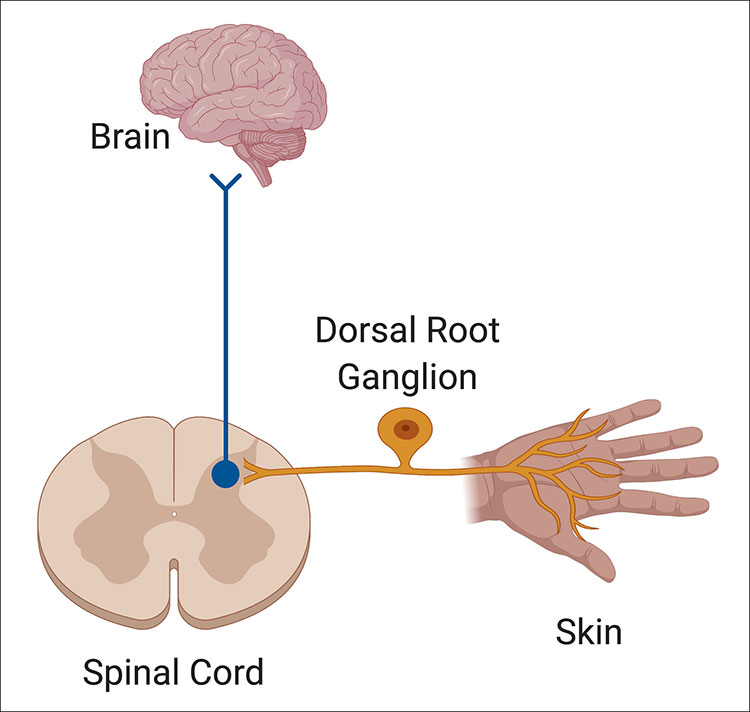

The answer lies somewhere in the circuitry connecting neurons underneath the skin with the brain. Neurons in the peripheral nervous system terminate in different layers of the skin, with receptors in a wide range of shapes and sizes. Some detect itch; others vibration, pressure, or pain. These receptors begin the relay of sensory information from skin to the nerve cell bodies housed in the spinal cord. The signal then travels up to the brain where conscious perception takes place. “We don't know where in this chain we're getting the ‘nice’ feeling,” Schaffler said. “Does it start at the skin?”

The answer may be a type of sensory neuron found in the dorsal root ganglia, a cluster of neurons in the spinal cord. Activating these neurons in mice results in feelings of pleasure and reward. Unlike other neurons in the dorsal root ganglia, these express a gene called MrgprB4. Only two percent of dorsal root ganglia neurons do so.

Schaffler and her lab mates blocked the neurons expressing the MrgprB4 gene, so all the cells died before the mice were four days old. Even though the mice grew up in a normal social environment and had an intact sense of touch, they could not perceive the rewarding aspects of touch.

As adults, the mice behaved the same as controls in an array of anxiety and depression tests; a difference only emerged once the mice experienced stress.

After three days of stress, the mice missing MrgprB4 neurons showed increased depression-like behaviors, including decreased grooming. Growing up without the ability to experience the rewarding aspects of touch may make mice more vulnerable to negative consequences from stress. The next round of research will investigate if activating these neurons makes mice more resilient to stress.

“This [study] is making another significant step forward,” said Francis McGlone, head of the Somatosensory & Affective Neuroscience Group and professor of neuroscience at Liverpool John Moores University. But the work is not over. “What we are really waiting for is the translational evidence [in humans].”

The main contender for an equivalent type of neuron in humans is a group of sensory nerves called C-tactile afferents. This class of nerve fiber responds only to gentle touch. The problem is, they aren’t easily studied. “We have no idea where they are,” McGlone said. “We don’t have a marker for them, [so] we can’t stain for them and identify where they actually terminate in the skin.” Plus, animal models of touch and pain have a history of not directly translating to humans.

Locating and studying these neurons in humans could usher in an era of depression treatments targeting the peripheral nervous system, rather than the brain itself. Current antidepressants offer relief along with a slew of side effects and can take weeks to start working. “Maybe it's time to start looking elsewhere,” Schaffler said.

Activating the right neurons in the skin could also provide the crucial benefits of a soothing touch for people living without it. “If you know that a particular vitamin is necessary for someone’s nutritional health, then you make sure they get that vitamin,” McGlone said. “I say the same thing about C-tactile afferents. It’s like a vitamin that maintains their mental health.” Maybe one day there will be “an emotional IcyHot,” Schaffler said, to give people the same emotional boost as a hug from a loved one.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

What to Read Next

Also In Touch

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org