Reality and our perception of it are not the same. While reality flows continuously, when we sit down to reflect on our day it seems to be organized into neat chapters.

According to event segmentation theory, this subconscious structuring of reality is a side effect of how our brains process perceptions. We constantly predict what will happen next, which is easy while doing a familiar task like making tea. But when we move on to a new task, like writing, what we know about making tea may not be useful in predicting our experiences writing. This failure to predict causes a boundary to form between the two events, creating a perception of neat chapters.

This is a video from the 2024 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

Created by Harry Johnson.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

Hi everyone, I'm Harry Johnson, and I'm a highly decorated cognitive neuroscientist from University College London. And what if I told you that the nature of reality is fundamentally different to our perception of it?

Well you might be thinking, "Oh dear, that isn’t particularly good news." Indeed, being in touch with reality we feel quite important.

But before jumping to conclusions, what even is reality in its unrefined, authentic form? And how is our experience different to it?

Well, reality presents itself as this kind of unyielding stream of change. It unfolds continuously, and it does so right before our very eyes, our ears, the tips of our fingers, our tongues, and our noses.

But it does so without gaps, without pause, and without inherent separability.

However, the talent of human experience is rather different. In the present moment, during perception, we experience reality as this ongoing series of separable events. We're always doing something, and at some point, the content of that something, changes.

For example, just this morning, I wrote the last chapter to my new autobiography, “Cognitive Neuroscience and Me.” After that, I went to the gym, and then I had a nice tea break. And now, I’m here talking to you.

In contrast to reality, which is inherently continuous and boundaryless, my experience, as I described it here, has structure. It consists of events that are somehow meaningfully separate from one another, organized in time.

But how is this possible? How do we get from continuous, dynamic activity to a structured perceptual experience?

Well, one way in which this might be understood is through the scope of Event Segmentation Theory.

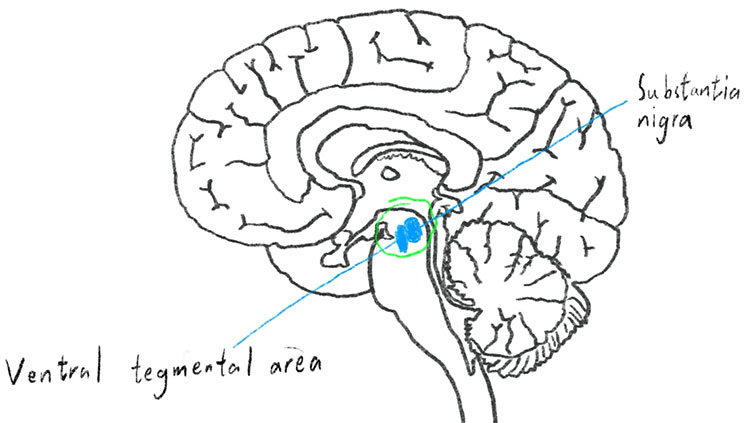

Event Segmentation Theory, or EST, is a theory suggesting that the structure of experience emerges as a byproduct of ongoing perceptual processing. Zacks and colleagues explain how this might occur using a model called the Perceptual Processing Stream.

According to this model, our perceptual systems are continuously formulating predictions about activity in the near future.

In order to facilitate such predictions, it is proposed that we maintain something called event models, which are stable, multisensory representations of what is happening in the present moment.

Event models themselves are guided by something called event schemata, which contain information about the structure and sequence of past events, providing a basis for prediction.

So, event models, guided by event schemata, bias perceptual processing, which yields predictions about activity in the near future.

But how does this relate to event segmentation?

Well, EST suggests that we have a mechanism which constantly compares our predictions of the near future to what actually happens.

If the predictions are accurate, they have high predictive value, which means that the current event model is doing its job and therefore it can be maintained.

However, when predictive value becomes low past a certain threshold, this indicates that the environment has changed, and thus the current event model ought to be updated, so as to regain predictive value.

Now, Zacks and colleagues argue that when transient prediction errors occur, we perceive a boundary. Events, on the other hand, are perceived during periods of stability when predictive value is high.

To use the example of making tea earlier, an event model would have been representing what was going on, whilst doing everything that encompasses making tea — for example, boiling the kettle, pouring water, stirring the milk, and so on.

That event model would have yielded reasonably accurate predictions, because everything I was doing was reasonably predictable in the context of making tea. So, here, I would have perceived an event.

However, when I finished making tea, that model no longer had predictive value because the context had changed. I was no longer making tea, so a boundary would be perceived at this point, constituting the end of making tea, and the beginning of my current event — talking to you.

Also In Thinking & Awareness

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org