Anthropomorphism: Seeing the Human in Plants, Pets, and Possessions

- Published4 Nov 2020

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Our love for talking animal cartoons has an evolutionary purpose: assigning human traits to non-humans kept our ancestors wary of potential dangers. Anthropomorphism activates parts of the brain involved in social behavior and drives our emotional connection with animals and inanimate objects.

This video is from the 2020 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

Created by Clodagh Towns

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

Do you find yourself feeling sorry for these flowers? If you do feel sorry for them, well, why do you feel sorry for them? They’re just flowers, they don’t have feelings! You feel sorry for them because you are anthropomorphizing!

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human qualities and internal states to non-human entities such as objects, plants, animals, and even the weather! It is an established component of human cognition. Children begin to anthropomorphize at as young as two years old during pretend play. Examples of anthropomorphism are evident throughout history and across cultures. For example, in storytelling — Frosty the Snowman, Winnie the Pooh, Thomas the Tank Engine, and also in practices such as giving fierce hurricanes human names.

But why do we anthropomorphize?

The anthropologist Stewart Guthrie suggested that we anthropomorphize because it would have been dangerous for our ancestors not to. While feeling sorry for flowers won’t benefit us in any way, failing to suspect malicious intent behind a rustling bush or disembodied eyes in the darkness, would have made our ancestors an easy target for stalking enemies. This theory is supported by observations that the impression of eyes, and motion cues, such as seemingly reactionary or deliberate movement, automatically trigger us to anthropomorphize.

Regarding anthropomorphizing of animals, Caporael and Heyes suggested that because of common behaviors across certain species anthropomorphism may help us to understand and predict animal movements. This is supported by observations that we are more likely to anthropomorphize animals which are more similar to us, or familiar to us. For example, we anthropomorphize vertebrates much more than invertebrates, and pet owners anthropomorphize dogs much more readily than non-pet owners.

So, what is going on in the brain when we anthropomorphize?

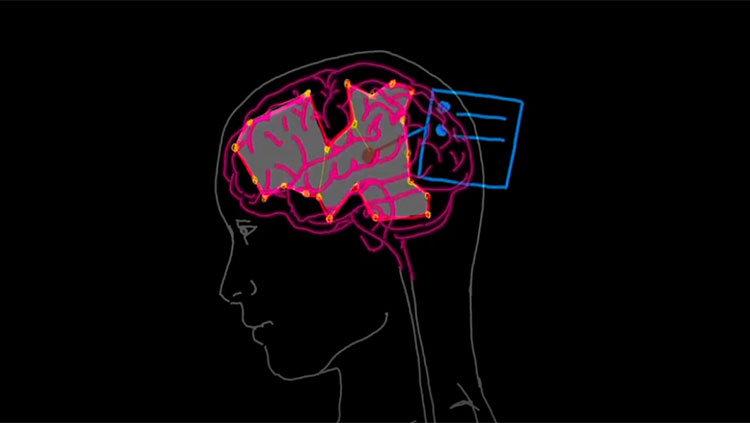

Researchers have found that the parts of the brain that are activated by anthropomorphizing belong to the same brain system, known as the social brain network, that we use to infer the thoughts, emotions, and internal states of other humans.

It has been shown that when people ascribe human dispositions to objects, they activate the superior temporal sulcus and the amygdala. Researchers have also compared peoples’ brain activity while viewing images of human, monkey, and dog facial expressions. They found that the same brain regions were used when making judgements about the emotions of all three! These included the superior temporal sulcus, the medial prefrontal cortex, and the lateral orbitofrontal cortex.

These findings that we use the same social brain network for perceiving thoughts and intentions in objects and animals as we do for other humans have important implications for our understanding of how we interpret and interact with our surrounding world, and provide insight into how and why we build emotional relationships with beloved pets and possessions!

Anthropomorphism also highlights moral and ethical considerations for society. For example, our attitude towards animal rights. We mass farm and slaughter animals that we perceive as being less intelligent, or incapable of feeling, while we pamper others as pets. We happily exterminate insects but have countless foundations for the preservation of vertebrate wildlife.

Another ethical consideration concerns the development of social robots and artificial intelligence. Both are purposefully designed to encourage people to anthropomorphize, as it will make them perceive the robot or AI as a realistic social presence with an inner mind. The ethical concern is whether it’s okay to allow users to believe the illusion of a reciprocal social relationship, which they may wrongly describe as one of mutual love and care.

The use of anthropomorphic prompts in these fields will have to be carefully monitored and the consequences fully considered.

There is still much to be discovered about the neural mechanisms underlying different types of anthropomorphism, and there is much to be learned from the study of anthropomorphism about how we perceive and interact with the world around us.

Also In Thinking & Awareness

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org

.jpg)