Does the Brain Process Sign Language and Spoken Language Differently?

- Published9 Oct 2018

- Author Michael W. Richardson

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Signed languages, just like spoken languages, form wherever groups of people require them to communicate. There are more than 130 recognized signed languages worldwide, and American Sign Language (ASL) is the fourth most common language in the United States. But the brain functions behind sign language remain a bit of a mystery. Mairéad MacSweeney, director of the University College London Deafness, Cognition, and Language Research Centre, explains the similarities and differences between signed and verbal communication, and how researchers are beginning to uncover the way the brain processes sign language.

What do we need to know about sign languages to understand how they work in the brain?

The first thing to understand is that signed languages are natural human languages. They evolve naturally wherever a group of deaf people need to communicate. Signed languages are fully capable of the same complexity as spoken languages. They are different based on country — British Sign Language and American Sign Language are very different, for example, even though a deaf American traveling in England would have no trouble reading English. Signed and spoken languages are complex linguistic systems that simply differ in how they are expressed and perceived.

What areas of the brain are used in spoken languages?

When answering this question, we first need to be clear about what aspect of ‘language’ we are talking about. We can speak, listen, read, and write spoken language, all of which entail a large number of complex processing steps.

What we have known for quite a long time is that for the vast majority of people, the left hemisphere is dominant in processing most aspects of language. We know this because people who have suffered damage to the left hemisphere of the brain — through a stroke or traumatic brain injury, for example — are much more likely to have difficulty speaking or understanding spoken language.

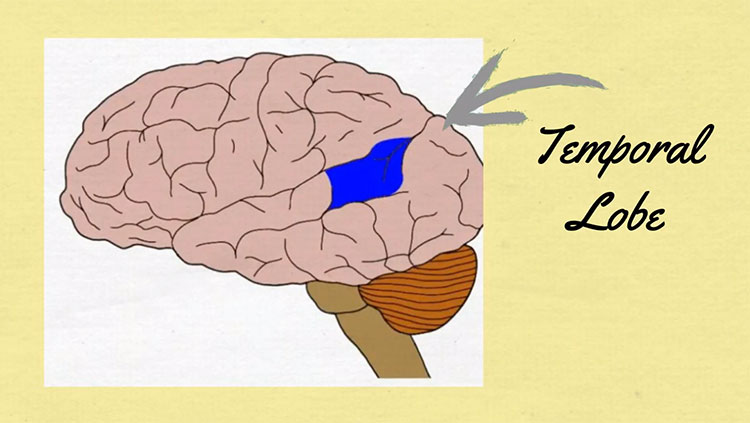

The left hemisphere houses a core language network. Broca’s area (in the front of the brain) is heavily involved in language production, while comprehension requires Wernicke’s area (at the side, towards the back of the brain). These areas were identified in studies of patients in the 1860s, but they are far from the whole story. In the last 20 years neuroimaging research shows that much of the brain is engaged in various aspects of language processing.

Do spoken and signed languages rely on the same areas of the brain?

The parts of the brain active in sign language processing are very similar to those involved in spoken language processing. When we compare the brain scans of deaf people watching sign language and hearing people listening to speech, there is significant overlap, especially in the core areas. This suggests that these areas do not distinguish between information coming in through the eyes or the ears.

There are, of course some differences. Hearing people listening to speech engage the auditory cortex, while deaf people watching sign language have greater activity in the parts of the brain that process visual motion. There are also subtle but significant differences in how the brain processes signed and spoken languages that occur beyond those sensory processing systems. Signed languages express spatial relationships much more easily than spoken languages. If you wanted to communicate that “the cup is on the table,” speakers must use words to explain it. A signer could physically express that concept by using one hand to sign ‘cup’ and the other to sign ‘table,’ by placing the former on top of the latter. When signers watch these types of sentences, they recruit the spatial processing capacity of the left parietal lobe more than when hearing people listen to these types of sentences.

Does the brain process signed and spoken languages in the same way?

Because there is so much overlap in the brain regions engaged during signed and spoken language processing, scientists have assumed the same linguistic computations are made in these regions. But it may not be that straightforward. While the strength of activation in these areas is very similar, our current work is focused on the pattern of activation in these regions. We hope this will tell us more about the representations being used within these regions. My colleagues and I are really at the very beginning of this investigation, but it is possible that there is less in common than we previously thought. Ultimately, while “the where” of all languages seem to be very similar, the “how” could be quite different.

This question was answered by Mairéad MacSweeney as told to Michael Richardson for BrainFacts.org.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Language

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org