The Hidden Effects of Hearing Loss on the Brain

- Published11 Apr 2022

- Author Christina Leimer

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

“How often do you wear your hearing aids?” she asked. “Only when I go out for meetings,” I told her. “I live in a quiet environment, and I’m sensitive to noise.” The audiologist was alarmed. I couldn’t distinguish between similar words like ‘wood’ and ‘hood,’ and background noises wiped out my ability to understand speech. After wearing hearing aids off and on for 30 years, my hearing was getting worse.

My hearing aids amplify many sounds, not just speech. High pitches grate, sharp sounds startle, and a chair scooting becomes a screech. The constant clatter makes me irritable. So, wearing the devices only when I needed to hear people seemed reasonable.

“You should be wearing them all the time!” she insisted, leaning toward me in her chair. “Use it or lose it.” She explained that without hearing aids, the auditory pathways to my brain weren’t getting enough stimulation.

That lack of stimulation can make hearing more difficult over time, potentially impacting cognitive ability and dementia risk. But hearing loss isn’t just about volume. While the ears collect sound waves and transmit them as electrical signals, your sense of hearing manifests only when the brain interprets those signals as sound.

The Brain Burden of Hearing Loss

“There’s good evidence that if you can’t hear well, your brain works harder [to understand sound and language],” says Jonathan Peelle, cognitive psychologist in the Department of Otolaryngology at Washington University in Saint Louis. When there’s a lot of background noise, multiple speakers, rapid speech, or complex sentences, people with hearing deficits strain to listen. This extra mental burden causes stress that shows up in multiple ways, like dilated pupils, failing to remember parts of conversations, or responding incorrectly. This type of stress can sometimes be mistaken for cognitive decline in older adults.

Such “effortful listening” may even divert other parts of the brain from their usual activity to help listeners with hearing loss understand speech. Yune Lee, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Texas at Dallas, saw potential support for this theory. In a 2018 study, his team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to monitor the brain activity of 35 adults aged 18 to 41 who had clinically normal hearing while they listened to sentences of varying complexities. “After about age 50-55, the right frontotemporal lobe comes in to assist [the left hemisphere] with language processing,” Lee says. “It’s part of the brain’s plasticity.” To researchers’ surprise, the young adults with lower hearing ability were using the right anterior prefrontal cortex, too. “We’re not sure what it exactly means that younger people with relatively poor hearing are already utilizing that right hemisphere,” Lee says.

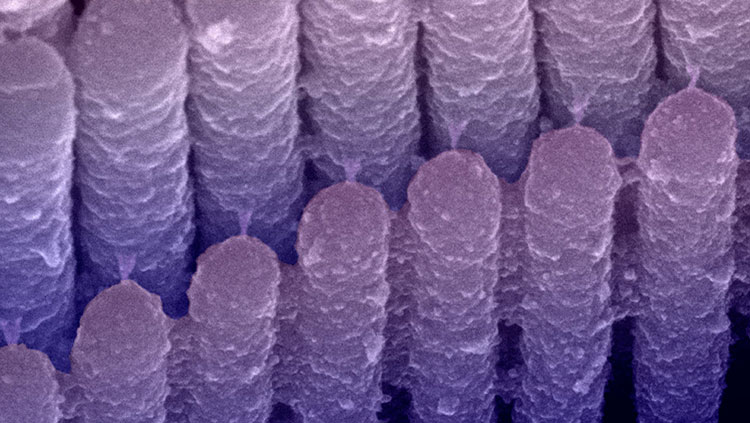

With so much effort required to hear, people often give up trying and withdraw from social activity. That withdrawal can lead to less auditory stimulation to the brain and potentially result in gray matter loss. And according to Peelle, multiple studies show people with hearing loss have less gray matter in the temporal lobe auditory regions. The outer surface (cortex) of these auditory regions is involved in tasks such as processing auditory stimuli, language comprehension, and speech perception. It may be that less auditory input over time makes those parts of the brain smaller because it has less to do.

“We know people with worse hearing have a smaller auditory cortex, but what we don’t know is why and does it matter,” Peelle says. “It feels like it would be bad to have less gray matter in your brain, but our brains are changing all the time. And I’m not aware of any studies showing that’s hurting people’s performance."

Hearing Loss and Cognitive Decline

Hearing loss also puts older people at higher risk for dementia. A study published in 2019 analyzed the retrospective 12-year data from 16,270 participants maintained in the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan. Researchers compared groups with a hearing loss diagnosis to those without to see whether the groups developed dementia at different rates. Overall, the dementia incidence rate was 17 percent higher among the hearing loss group. Unlike many hearing loss studies, this one included middle-aged people. Compared to normal-hearing counterparts, people who developed hearing loss between the ages of 45 and 64 were more likely to develop dementia later in life. This wasn’t true for people who were diagnosed with hearing loss later.

“Not everyone with hearing loss will get dementia,” says Jennifer A. Deal, a researcher at Johns Hopkins University during her presentation in the 2021 Memory Matters Virtual Talk Series. It’s possible hearing loss and dementia aren’t linked by anything other than the fact people are aging – developing independently from one another. However, if they are linked, Deal suggests some potential mechanisms that scientists are exploring.

Deal notes hearing loss may cause diminished activity in cognitive processing regions, leading to loss of brain mass over time. People with hearing loss can also experience social isolation and loneliness, which reduces brain stimulation and may impact thinking ability. What’s more, Deal points out that the extra effort needed to hear and understand speech can shift the brain’s resources, potentially impacting the ability to do things like making a memory.

There’s some evidence that the brain’s plasticity may overcome some deficits when people use hearing aids, but the changes could be irreversible for many. An answer to this question could be coming in 2022 via the ongoing Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) study when it begins to produce results. This multicenter randomized control trial is examining if hearing treatment delays cognitive decline in 977 older adults.

The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging, recruited people with untreated mild-to-moderate hearing impairment to better understand how cognitive decline develops over three years across two intervention groups: one receiving best-practice interventions for hearing loss and the other receiving health education interventions for successful aging.

“I think it unlikely that hearing aids can ever reverse cognitive decline,” said Deal, one of the researchers on the study, “but we are hopeful that they can help prevent, or at least delay, future decline.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Chien, W. W. & Lee, D. L. (2021). Physiology of the Auditory System. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 128, 1945-1957.e3. Elsevier. https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/book/3-s2.0-B9780323611794001289. Retrieved March 25, 2022 from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/auditory-cortex

Deal, J. A., Goman, A. M., Albert, M. S., Arnold, M.L., Burgard, S., Chisolm, T., Couper, D., Glynnh, N.W., Gmelini,T., Hayden, K.M., Mosley, T., Pankow, J.S., Reed, N., Sanchez, V.A., Sharrett, A.R., Thomas, S.D., Coresh, J. & Lin, F.R. (2018). Hearing treatment for reducing cognitive decline: Design and methods of the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 4(4), 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2018.08.007

Deal, J.A., Hearing Loss & Dementia: What’s the Connection? (n.d.). Www.youtube.com. Retrieved January 18, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IzsOW8g9xR0

Griffiths, T. D., Lad, M., Kumar, S., Holmes, E., McMurray, B., Maguire, E. A., Billig, A. J., & Sedley, W. (2020). How Can Hearing Loss Cause Dementia? Neuron, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.08.003

Hearing Loss Facts and Statistics. (n.d.). https://www.hearingloss.org/understanding-hearing-loss/hearing-loss-101/hearing-loss-by-the-numbers/

Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. (2021). Hearing Loss & Dementia: What's the Connection? Memory Matters Virtual Talk Series. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IzsOW8g9xR0

Lee, Yune S. “Impact of Subtle Hearing Loss on the Cognition of Young Adults.” The Hearing Journal, vol. 71, no. 10, Oct. 2018, p. 30, 10.1097/01.hj.0000547401.21466.27. Accessed 6 Oct. 2019. https://journals.lww.com/thehearingjournal/fulltext/2018/10000/impact_of_subtle_hearing_loss_on_the_cognition_of.6.aspx

Liu, C.-M., & Lee, C. T.-C. (2019). Association of Hearing Loss with Dementia. JAMA Network Open, 2(7), e198112. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8112

Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne, C., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Costafreda, S. G., Dias, A., Fox, N., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Kivimäki, M., Larson, E. B., Ogunniyi, A., Orgeta, V., … Mukadam, N. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet (London, England), 396(10248), 413–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

McCormack, A., & Fortnum, H. (2013). Why Do People Fitted with Hearing Aids Not Wear Them? International Journal of Audiology, 52, 360-368.

Wingfield, A., & Peelle, J. E. (2012). How does hearing loss affect the brain? Aging Health, 8(2), 107–109. https://doi.org/10.2217/ahe.12.5

World Report on Hearing. (2021). In World Health Organization (pp. 1–252). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-hearing

Also In Hearing

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org