Having an audience activates parts of the brain involved in reward and social behavior, influencing your ability to complete a task.

This video is from the 2020 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

Created by Isla Jones

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

Have you ever practiced something to perfection, only to find that when you do it in front of someone else, you mess up? Or maybe you are spurred on by someone watching you, and you push yourself to perform even better.

The presence of other people can change our behavior in many different ways. This is known as the audience effect. This effect is robust and can also result in various changes in the body, such as a raised heart rate. The audience effect can arise even when we can’t actually see the audience. Just believing that we are being watched is enough to cause these behavioral changes.

Over the years, there has been a lot of research into the audience effect, and the processes underlying it in the brain. The audience effect was first described in the 1800s, in a study investigating cyclists’ speed records. Results showed that people cycled faster while competing with others than when they were alone.

However, being watched by other people doesn’t always enhance performance. For example, researchers have suggested that people may be worse at mental arithmetic while being watched than when alone.

The cognitive mechanisms underlying this effect seem to be quite complex and are not yet fully understood. One theory suggests that this effect is driven by increased arousal due to being watched by another person. It has been argued that this impacts performance in different ways depending on the context — for example, people may perform better at easy tasks, but worse at hard tasks when being watched. However, others believe the effect is a result of more complex mechanisms relating to self-presentation or reputation management.

Neuroimaging methods can provide insight into the processes in the brain that may underlie the audience effect. One study used functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, to investigate the audience effect in the context of donation tasks. While in the scanner, participants freely decided whether to donate money to charities, or to keep the money for themselves. On some trials, they believed their choices were being observed by two people outside of the scanner, and on other trials these observers were believed to be absent. Results showed that being observed not only increased donation rates, but also increased activation in the ventral striatum, a brain area associated with reward, when participants were seen to be donating.

This evidence suggests that the audience effect impacts brain activity as well as behavior. Another study using fMRI asked participants to complete a task while in front of a camera inside the scanner. Participants were told there would be an audience on some trials, where they would be visible to their peers. They were shown a red light when the camera was on, to indicate that they were being observed.

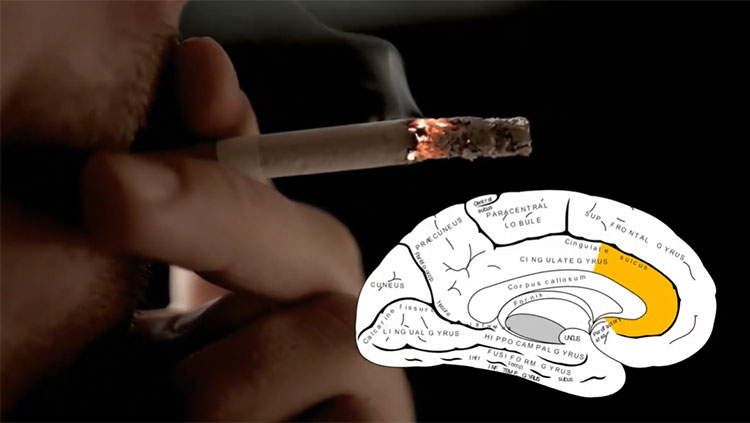

Results showed that when participants believed they were being watched, brain activity increased in the medial prefrontal cortex, a region associated with the processing of information about the self and involved in other social processes. In addition, increased connectivity between this area and the striatum, an area involved in processing reward, was found.

This study examined participants in different age groups and found that these effects were stronger in adolescents than in children or adults, which may suggest that adolescents are more concerned about their reputation than other age groups.

Past research investigating the neural processes underlying the audience effect has implicated the medial prefrontal cortex, but more work is still needed to fully understand the neural and cognitive mechanisms underlying this effect.

In order to learn about processes underlying social interactions, it is important to carry out research in natural environments. Since studying the audience effect in a realistic and natural way ideally involves face-to-face interactions, it can difficult to explore this in the restrictive environment of an MRI scanner, where you’re basically stuck in a small tube unable to see around you.

Studying the social brain can be particularly challenging, but this is a very exciting and important field of neuroscience, with potential to help us understand more about how the brain works as a whole.

Also In Emotions, Stress & Anxiety

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org