To Sleep, Perchance to Be Less Hostile

- Published19 Jul 2019

- Author Elisa Shoenberger

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

“Sleep on it” is the common adage prompting us to slow down and take time to think before making decisions. Turns out, this age-old expression might have more science to it than previously thought, connecting sleep — or lack thereof — to our emotional state. For decades, researchers have been documenting how sleep deprivation impacts both emotions and how we relate to the people around us.

“Our brain helps us figure out whether something is worthy of attention. But when people are deprived of sleep, the brain cannot make that decision,” said Eti Ben-Simon, a neuroscience postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science in the University of California Berkeley. “Everything seems to require our attention, which can be tiring.”

Ben-Simon has been studying the impact of sleep deprivation to see how it influences our emotional reactions. One of Ben-Simon’s 2015 studies suggests sleep deprived people have difficulty tuning things out, noting that subjects who were kept awake all night were having difficulty ignoring data considered neutral. She found that “events that are considered neutral” when well-rested, “are considered more negative following a night of sleep loss.” In other words, people who didn’t have enough sleep perceived more things — even the most straightforward information — as negative and it was reflected in their brain activity.

An Angry Face

Other studies also have shown that people seem to judge neutral situations more negatively when they haven’t had enough sleep. Another 2015 study from UC Berkeley asked subjects to judge faces that changed from threatening to neutral while in a fMRI scanner. Study participants completed a task of judging 70 computer-generated Caucasian faces when they were well-rested and then sleep deprived for 24 hours. Seven versions of each face morphed “from not threatening to increasingly threatening.”

Non-threatening faces tended to have relaxed eyebrows, eyes, and mouth while threatening faces had arched brows, narrowed eyes, and pursed lips. Researchers found that “sleep deprivation impairs the basic ability to recognize emotional from a non-emotional face stimuli.” In short, people who were kept awake all night judged many more faces as threatening than non-threatening compared to when they were well-rested.

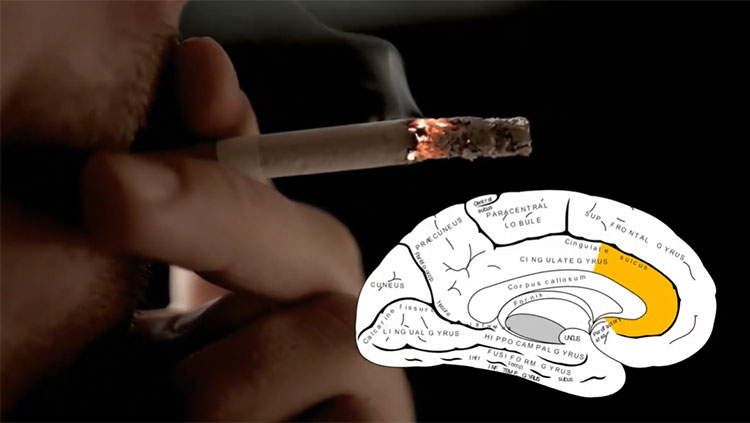

Ben-Simon explains that in these studies, researchers are seeing that the amygdala, which deals with emotions, becomes more active when dealing with emotional stimuli coupled with sleep loss. At the same time, the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates emotion, becomes less active. When higher-regional brain activity measured by fMRI is presented as hotter colors (i.e., red, yellow, or orange), scans show that emotional stimuli evoke a ‘hotter’ amygdala (lighting up red, yellow, or orange) and ‘cooler’ prefrontal cortex (lighting up blue or purple) following sleep deprivation. So, when you lose sleep, you become more sensitive and your ability to control your emotions lessens.

“Basically, every function that serves us during wakefulness goes away without sleep,” said Ben-Simon. Things like our ability to think, our emotions, and memories, need sleep to work best. “When you follow people who are sleep deprived, you gradually see all these functions turn off one after another.”

If sleep deprivation lessens the brain’s ability to adequately perceive threat, this impacts how we perceive other emotions. William Killgore, a clinical neuropsychologist at the University of Arizona, did a 2017 study that had sleep deprived subjects judge faces that were mixes, or complex blends of two different emotions like the 2015 study at UC Berkeley. When the subjects lacked sleep, they had a harder time identifying happiness and sadness. Their recognition of the other emotions — surprise, anger, and fear — didn’t change much from when they had slept well. Killgore theorizes that these three emotions were needed for survival: “If you were a primitive caveman and a lion were creeping up behind you to attack, it would be helpful to be able to read fear in your fellow caveman’s face or to identify surprise. This would save your life. Or if your fellow caveman is going to kill you, you need to identify anger.” But happiness and sadness are more social emotions. “You probably aren’t going to die if you don’t get that hug at that moment,” said Killgore. “But you have to deal with that lion.”

Sometimes You Need a Hug — and a Pillow

Amie Gordon, a psychologist at University of California San Francisco, has been studying the impact of sleep on relationships. In Gordon’s 2013 study, researchers studied the impact of sleep quality on relationships in a two part study.

The first part had couples self-reporting the quality of sleep as well as the amount of conflict experienced within the relationship over two weeks. The second part had couples come into the laboratory to be videotaped. Researchers asked each partner to discuss the top three areas of conflict in their relationship and then the couple had five minutes to work toward a resolution of one issue chosen by one partner. In part one, researchers found: “poor sleep one night was associated with greater conflict the following day across a two-week period.” In part two, researchers found that poor sleep was associated with the empathic accuracy of couples even if only one person had sleep issues. Both people had difficulty assessing the other person’s emotions whether or not one person had slept well. Moreover, they found that it may hamper conflict resolution.

Gordon theorizes that the person with sleep problems may not be conveying the right information so it’s harder for their well-rested partner to understand what is going on. And of course, the sleep deprived person can’t judge their partner’s emotions, perhaps making couples more susceptible to conflict and have a harder time resolving issues.

In a 2006 study, Killgore explored how sleep loss impacted people’s frustration and likelihood of blaming other people. Using the Rosenzweig Picture-Frustration cartoons, participants were shown a cartoon depicting two people in an ambiguous situation. In the cartoon, one person would have a pre-recorded response and the other person would have an empty speech balloon. Researchers asked participants to fill in empty speech bubbles in the cartoons. For instance, a cartoon might show a couple in front of a car where the wife mentions lost car keys and subjects would have to fill in the speech balloon to represent what the man in the cartoon said in response.

Subjects took the test twice, once while they were well-rested and the second time after the study had kept them up for two nights. Their study showed that people were more likely to use blaming language and were less likely to find ways to resolve conflict when sleep deprived compared to when they were well-rested. For instance, in the car key cartoon, sleep deprived subjects had the husband blame his wife about losing the keys instead of trying to resolve the issue more often than when they had slept. People with sleep loss were more likely to use language like “shut up” as well.

Killgore explains, “If the first thing that pops in your head is to blame the other person when you are sleep deprived” that could lead to conflict. However, he notes getting the full picture of the effect sleep loss has on relationships means undertaking more research.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Discussion Questions

1) What impact does sleep deprivation have on decision making?

2) What impacts can sleep deprivation have on relationships?

References

Goldstein-Piekarski, A. N., Greer, S. M., Saletin, J. M., & Walker, M. P. (2015). Sleep Deprivation Impairs the Human Central and Peripheral Nervous System Discrimination of Social Threat. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(28), 10135–10145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5254-14.2015

Gordon, A. M., & Chen, S. (2014). The Role of Sleep in Interpersonal Conflict: Do Sleepless Nights Mean Worse Fights? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(2), 168–175. doi: 10.1177/1948550613488952

Kahn-Greene, E. T., Lipizzi, E. L., Conrad, A. K., Kamimori, G. H., & Killgore, W. D. S. (2006). Sleep deprivation adversely affects interpersonal responses to frustration. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(8), 1433–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.06.002

Killgore, W. D. S., Balkin, T. J., Yarnell, A. M., & Capaldi, V. F. (2017). Sleep deprivation impairs recognition of specific emotions. Neurobiology of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms, 3, 10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nbscr.2017.01.001

Simon, E. B., Oren, N., Sharon, H., Kirschner, A., Goldway, N., Okon-Singer, H., … Hendler, T. (2015). Losing Neutrality: The Neural Basis of Impaired Emotional Control without Sleep. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(38), 13194–13205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1314-15.2015

Also In Emotions, Stress & Anxiety

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org