Art Celebrates Science in ‘Life of a Neuron’ Exhibit

- Published28 Sep 2022

- Author Lisa Seachrist Chiu

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

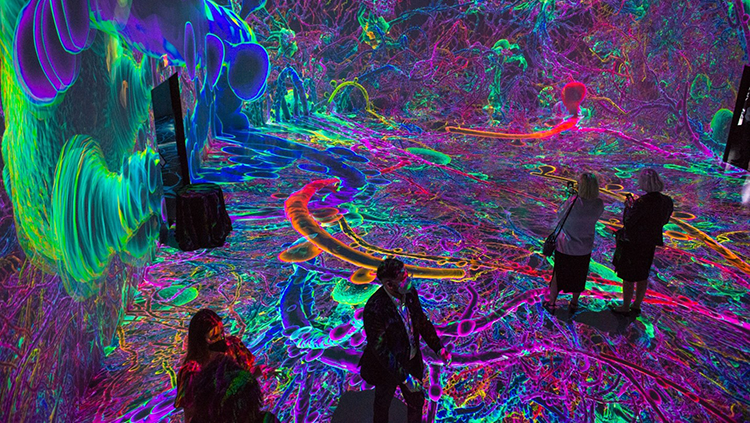

As he descends a blue-lit staircase to a wondrous, slightly eerie soundtrack, Sandro Kereselidze welcomes a virtual audience to ARTECHOUSE — a space dedicated to experiential art, science, and technology — launching the Neuroscience 2021 Dialogues Between Neuroscience and Society: Life of a Neuron lecture. Introducing himself as a proud immigrant from Tbilisi, Georgia, and the scion of six generations of artists, Kereselidze, ARTECHOUSE founder and chief creative officer, steps into a high-ceilinged room where an enormous projection of a human neuron in blue, green, yellow, and purple fills the floor, walls, and ceiling of the space.

Kereselidze is standing in the cerebral cortex: the wrinkled, outer layer of the brain responsible for higher cognitive functions. A looped, 20-minute animation depicts the life cycle of the cortex’s pyramidal neurons from pre-birth to death. Lime green, egg-shaped cells radiate long fibers, and a baby can be heard babbling. Next comes sounds of the schoolyard with a forest of pink and purple neurons. The end of the loop zooms in on an undulating pale-yellow neuron, its surface mottled like the moon. It grays and stiffens, and eventually snaps like aged elastic.

The immersive, data-based art that brings neuroscience principles to life is the culmination of a three-year collaboration between the Society for Neuroscience (SfN) and ARTECHOUSE, developed as a celebration of SfN’s 50th Anniversary. SfN President Barry Everitt discussed the project’s process, challenges, and impact with Kereselidze, Riki Kim, ARTECHOUSE executive creative director, and John Morrison, UC Davis professor and director of the California National Primate Research Center.

“I've heard you talk many times over the years, John, about how one of your fantasies was to get inside a 3D actualization of a neuron,” Everett said. “You wanted to visualize it, and then experience it. And, I'm just wondering how this amazing project aligned with what you had in mind?”

“Oh, it's beyond what I had in mind,” Morrison responded. “So, I think the first time I saw a virtual reality cave, very many years ago, my first thought was: I want to be able to walk through a neuron.”

The spark for Life of a Neuron came in 2017, when Morrison, as BrainFacts.org’s editor-in-chief, was feting the completion of an animated, interactive, 3D brain. He turned to SfN’s executive director, Marty Saggese, saying “now I want to develop a virtual neuron that you can walk through and watch it mature, watch it get disease, and watch it heal.”

“And Marty took it seriously and put the wheels in motion for what we called the Neuron Project.” An amorphous concept that Morrison maintained needed to be based on a human neuron that was quantitatively and accurately reconstructed. “As it turned out, that was much harder than we thought it would be.”

Morrison was part of the neurobiology team that isolated and reconstructed the neuron from tissue donated from a brain surgery. It included Dani Dumitriu, at Columbia University, Corrado Cali, now at the University of Turin, William Janssen, at Mount Sinai, and Matt Wimsatt, at Jackson Labs. After injecting the cells with a fluorescent dye, the team slid the sample under a high-resolution microscope. But the microscope only offers a 2D glimpse. At most, you can see a tenth of micron in depth, Morrison says, and neurons occupy a space of hundreds of microns. With assistance from Vimal Gangadharan at ZEISS, the team built the 3D model by taking a series of thousands of images and using software to stack those images on top of each other and stitch them together.

The model still didn’t reveal what’s inside the neuron. They needed Cali to deploy electron microscopy. With 100 to 1,000 times the resolution of a light microscope, electron microscopy brings a neuron’s inner world into focus — from the mitochondria powering the cell to the vesicles packaging and delivering proteins.

At this point, all that was left was to put the internal anatomy into the first reconstruction. “Corrado Cali was the EM expert, and Matt Wimsatt was the 3D expert, and they just developed a way to do this. I’m not sure anyone has done this before,” Morrison says. “Normally, you would take these data sets and work on them independently. But we had to put them back together because we had to give [the visualization] to the artists.”

Weekly calls between SfN and ARTECHOUSE allowed them to plot out how the neuron would be presented once completed. Using the Brain Facts book as a reference, Kim saw a storyline — chapters 6 through 9 outline brain development from fetus to infant, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and aging. “It read like the life of a neuron,” Kim said. “A story that everyone goes through.”

The main exhibit reflects those stages of life, Morrison notes. In the fetus, the neurons are round balls migrating through space; infancy displays copious spinal plasticity; adolescence brings rampant neural activity; adulthood offers some stability, while aging features neuronal demise. “What’s amazing is the artists did all that art with basically the one neuron we gave them and some 2D Golgi images,” he said.

Kim pointed out the artistic team started work not with the main exhibit, but the side exhibits highlighting vision, addiction, and stress. The process began with “one pager” descriptions of the science associated with each topic.

“We put out a request for proposals from a set number of artists who we knew could comprehend complex concepts and work with scientific data,” Kim says. Once they had chosen the strongest concepts, robust and frequent conversations with the scientific advisors — Eric Nestler for addiction; Bevil Conway and Bob Wurtz for vision; Dani Dimitriu and John Morrison for stress — ensured there was actual science behind the concepts.

To guarantee scientific accuracy while providing artistic freedom, SfN and ARTECHOUSE developed a set of guiding questions for artists to revisit throughout the project process:

- How can art be used to demonstrate a concept in a way that a text cannot fully appreciate?

- How does the art correctly represent or utilize the science?

- How does the inclusion of an idea contribute to the framework of a life story?

- What are the most important takeaway messages for this concept?

- How does the art further the understanding of the science?

- How does the art piece celebrate and highlight that science?

“The vision exhibit is probably the most literal, and the addiction and stress side exhibits are the most artistically expressive,” Morrison said, noting that reflected the science where “there is still a bit of mystery with addiction and stress, but we really understand vision.”

Everitt agreed, but also pointed out that the portrayal of addiction didn’t focus on the reward and super activity of dopamine neurons. And the neurons looked very unhappy. Kim pointed out the artistic concept is that the people represent the drug, and the neurons respond to the number of people becoming less healthy as more “drug” enters the space.

“I think what was fascinating about this whole collaboration is that we were really, truly working together to create something that tells a story and tells the story in a scientific way correctly and also artistically,” says Kereselidze.

A central feature of the artistic expression for the exhibit came from a conversation between Morrison and Kereselidze about the effect of sound on the brain. Kereselidze’s father was a movie director who once told him music is the key for storytelling. “It was a challenge, but an interesting challenge,” he notes. “How can we tell a story with beautiful images but add another layer? From an experiential standpoint, I think that soundtrack takes the visitor to the next level of emotional connection with the art.”

With that connection, Kereselidze hopes Life of a Neuron can have a greater impact. “The next generation of neuroscientists might be walking into [the exhibit] today and experiencing something that inspires them,” he said. “And the next generation of artists see that they want to use the technology as a medium to express themselves. They both leave with curiosity, and that is the magic moment.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In The Arts & The Brain

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org