The Very Direct Effects of Indirect Costs

- Published8 Apr 2025

- Author Stuart Firestein

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

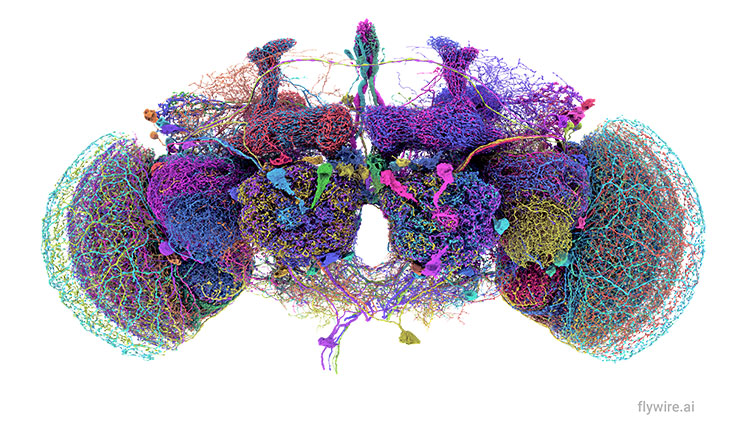

I am a scientist studying the effects of small molecules on receptors in the brain — from the sense of smell to the action of transmitters in neuropathologies, for example, the critical role of dopamine in Parkinson’s. My laboratory has published over 100 papers, and I have trained more than 25 graduate students and postdocs, most of whom now run their own labs in universities or industry. I pay no rent for my lab. Nor do I pay for electricity or heat. I have no secretary or administrative personnel. I do not have a purchasing agent, and I get deliveries to my lab for free. I do not manage or pay for the safe disposal of chemicals or biologicals, security, maintenance, or janitorial services.

My laboratory could not exist without all of this facilities and administrative support, but not one cent of my research funds goes toward any of these utilities or services. The university provides all of this, and the cost of doing so is largely covered by the misnamed “indirect costs” that are added on to any grant I get to support our research. On February 7, the National Institutes of Health issued guidance limiting indirect cost rates for all new and existing NIH grants to 15%. The rate is below what most grant recipients had previously negotiated. A Massachusetts federal judge issued a preliminary injunction blocking NIH’s cutbacks on March 5. This injunction was converted from temporary to permanent on April 4. The U.S. government has until April 14 to appeal.

Ironically, this system of paying these costs to universities, hospitals, and medical schools where research is done was a plan intended to reduce the size of the federal scientific bureaucracy and decentralize scientific research to spread it throughout the country. This was opposed to the then-current model in which all research was conducted in government institutes while universities were primarily responsible for teaching. This dates back some 80 years to the end of World War II. The U.S. found itself with immense scientific knowledge and infrastructure that had added to their advantages during the war. A famous report presented to President Harry S. Truman in 1945 by Vannevar Bush titled “Science, The Endless Frontier,” devised a plan to have universities administer and manage scientific research, which the government would pay for without having to build and run additional massive institutes and infrastructure of its own.

This strategy has been immensely successful in many ways, as can be seen from the advances in medical care and the reduction in suffering and diseases post-World War II. During the same period the Soviet Union, where research was closely managed and controlled by the government, produced not one useful drug or medical advance, while the U.S. conquered polio and other transmissible diseases, advanced cancer treatment, increased the healthy lifespan of Americans by more than a decade, regulated blood pressure and cholesterol, treated diabetes, and more. This plan also distributed scientific research to universities and hospitals throughout the country, providing jobs at many levels and numerous other economic benefits to their communities.

These are the very direct effects of so-called indirect funds.

In short: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

What to Read Next

Also In Supporting Research

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org