Brief: The Developing Adolescent Brain

- Published4 Mar 2016

- Reviewed4 Mar 2016

- Author Hilary Gerstein

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

In early December, members of Congress, their staff, and members of the scientific community learned about what’s happening in the brains of their children and, in the case of some of the younger staff, themselves.

At the Congressional Neuroscience Caucus briefing on the developing brain, leaders in the neuroscience field explored the fundamental differences between the growing and fully developed brain. Speakers included Lisa Freund, chief of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Frances Jensen, professor and chair of the department of neurology at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

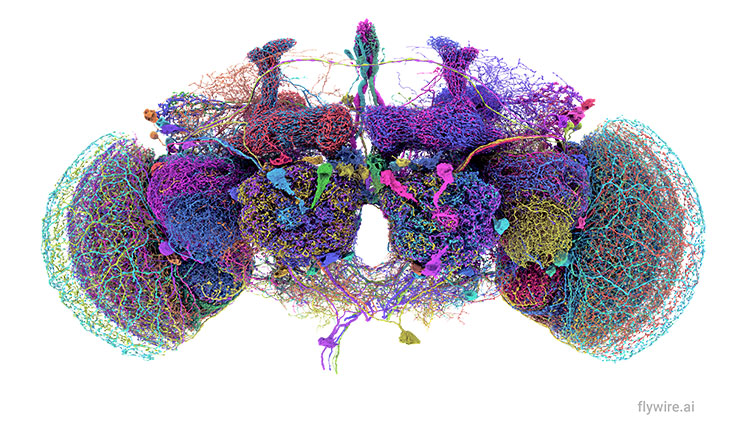

“Your brain develops into young adulthood, the late 20s and early 30s for most people,” Freund said, even though 80 percent of all your neurons are in place by age two. She explained how brain development in early childhood is more about making connections between cells than about changing the number of cells in the brain. New connections between cells are added, but only ones that are used frequently stay put. The rest are removed or pruned away so the brain can focus on only the necessary connections as development continues through adulthood, Freund said.

Jensen’s interest in the teenage brain came from a personal place — she was looking to understand her own teenage sons. After diving into studies on the adolescent brain, she shared her findings and firsthand experiences in a popular science book, The Teenage Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Survival Guide to Raising Adolescents and Young Adults, and with the crowd gathered at the briefing.

“They’re learning machines!” Jensen said, referring to the teen brain’s high level of flexibility or “plasticity.” Neurons in an adolescent can build connections to other cells twice as quickly as neurons in an adult brain, which allows teens to absorb new information at a rapid-fire pace but also makes their brains more vulnerable to negative influences. Stress, poor sleep, alcohol, and drugs of abuse all have dramatically larger effects on the brain of a young adult, making them particularly sensitive to addiction, a form of “learning” that most people would like to avoid. Additionally, because the part of the brain responsible for planning and weighing consequences is among the last to develop, teens have little foresight and are prone to risky behavior, a fact already well known by many parents.

Both speakers touched on topics relevant to policy on the Hill, such as the need for early interventions for disadvantaged children and how children and young adults should be treated within the justice system.

The Congressional Neuroscience Caucus was founded, and is currently co-chaired, by Representatives Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) and Earl Blumenauer (D-OR). The briefing was sponsored by the American Brain Coalition, the Child Neurology Society, and the American Academy of Neurology.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Supporting Research

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org