Steve's Deep Brain

- Published13 Sep 2018

- Reviewed13 Sep 2018

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Parkinson's patient Steve Gilbert, PhD, helps viewers understand his disease and his choice of deep brain stimulation (DBS) for treatment of tremor. This video gives examples of ways that tremor used to prevent him from some activities, and how his successful DBS has improved his daily life.

This video is from the 2018 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

Steve: When you have Parkinson's you have a lot of different things taken away from you. One important one was walking. I always liked walking. My Parkinson's was bad enough that I could not respond quickly to changes in the environment It was hard for me to get started, and you'd freeze when you tried to make a corner and I'd just get stuck And I remember thinking when I first had Parkinson's, how do you get stuck. How do you not be able to walk? But sure enough, that's exactly what happens. You get stuck. You just can't initiate movement.

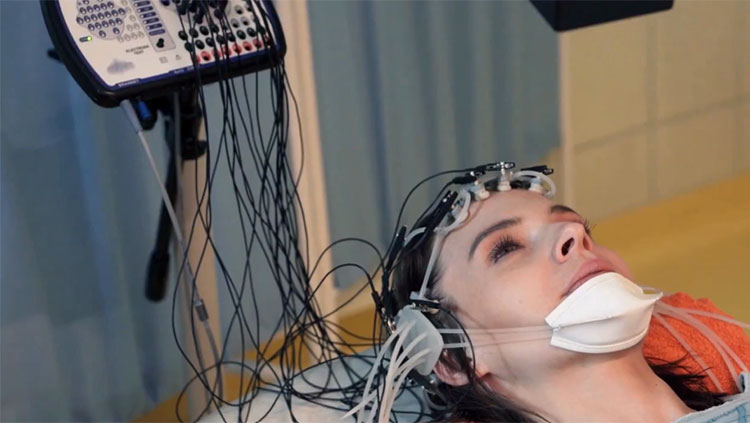

Narrator: Steve Gilbert is a Seattle scientist, researcher, and educator who has studied how toxins damage the brain for his entire academic career. In 2005 he was diagnosed with a brain disorder of his own, Parkinson's disease He'd noticed a tremor in his right foot for a few years before his formal diagnosis Once he was diagnosed he tried taking some of the medications that are often prescribed, but he didn't like the side effects.

Steve: Something had to be done because I was not taking any drugs My symptoms were getting worse. I was becoming increasingly debilitated. I couldn't travel by myself anymore. And I couldn't drive. The pleasures of life were just being gradually taken away. With DBS I procrastinated because the side effects are stroke, potentially, or brain infection. And for me, as a scientist, they couldn't tell me how it worked despite the risks.

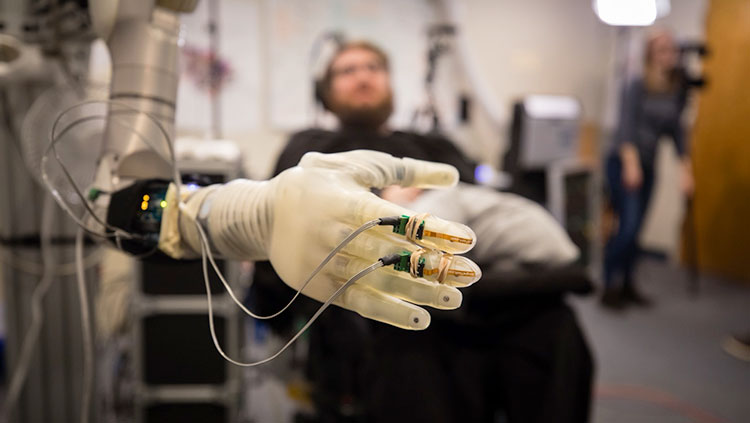

Narrator: Steve eventually agreed to have a surgical procedure called deep brain stimulation The surgeon would put two wires in his brain called leads. About a week after that Steve's surgeon put a pacemaker device near his collarbone that would direct the two wires to send out electrical impulses. These impulses, carefully targeted to his brains motor control center, were intended to interrupt Steve's tremors. Steve had to wait a month to find out if the treatment had worked.

Steve: You go through all this to have brain surgery, and it's fairly invasive stuff, and then they implant the generator and they make you wait. You wait, wait wait So I had all these people in the room, waiting to see. And they turned it on. And it worked great. And I could get up out of the chair. Because getting up, standing up is really difficult. You are trying to get your balance straightened out. So I could get up out of the chair, I could walk down the hall and back. It was incredible.

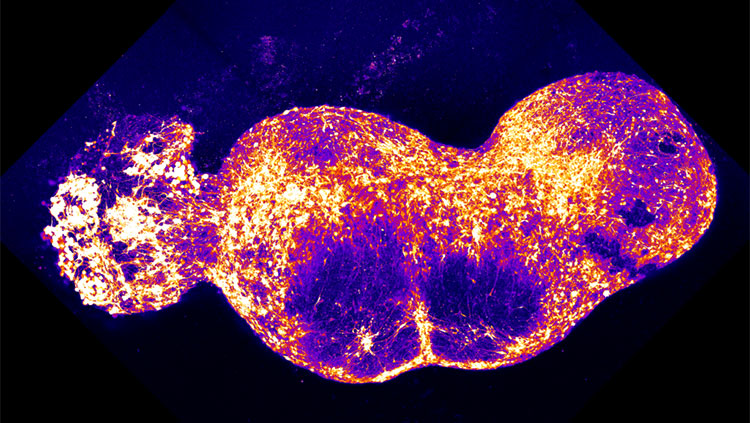

Narrator: Parkinson's disease damages a part of the brain that makes a chemical called dopamine. It is the absence of dopamine that leads to the involuntary movements known as tremors. But why electrical stimulation quells the tremors is not entirely understood. Steve has a device that allows him to change the impulse sent to the leads in his brain. Making the impulses stronger or weaker can change the tremor Steve is one of a minority of patients who are eligible for deep brain stimulation It's not right for everyone. But he's part of a huge group--an estimated 60,000 people-- diagnosed every year in the U.S. He thinks DBS could help more people and help them earlier.

Steve: There's a lot to know about deep brain stimulation. But one of the things to know is it can be phenomenally good feeling that I could walk around and the tremor was gone. It was just unbelievable.

Also In Tools & Techniques

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org