Figuring Out Why Alzheimer's Disease Strikes More Women Than Men

- Published15 Nov 2018

- Reviewed15 Nov 2018

- Author Kayt Sukel

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Alzheimer’s disease is well known for its devastating effects on millions of older people who lose basic cognitive abilities such as memory and thinking. Less known is that the disorder strikes women at such a disproportionate rate that some researchers call Alzheimer’s a “woman’s disease” and are urging research into the staggering sex disparity.

“We know that more women than men develop Alzheimer’s. We also know that women decline faster. But we don’t understand why,” says Pauline Maki, director of women’s mental health research at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Maki, chair of the Society for Women’s Health Research Interdisciplinary Network on Alzheimer’s Disease, and her colleagues are urging academia, government, and industry to invest in the research needed to understand this sex disparity in an effort to improve prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for both women and men.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, approximately two-thirds of the roughly 5.7 million people living with Alzheimer’s in the United States are women. Yet, little is understood about the neurobiological mechanisms behind these sex differences. Understanding the mechanisms could point to new treatments for everyone — female and male — suffering from the most common form of dementia.

“Alzheimer’s disease is an extremely costly condition. We’re looking down the barrel of $20 trillion in Alzheimer’s and dementia-related expenses by 2050,” Maki says, referring to projected costs including medical and nursing home services as well as the “physical, emotional, and financial support” required by unpaid caregivers, over the next 32 years. What’s more, there are currently no drugs to treat Alzheimer’s pathology — just a handful of drugs that can help alleviate the disorder’s symptoms.

Joseph Masdeu, director of the Nantz National Alzheimer Center at Houston Methodist Hospital, says that sex is a “very relevant variable” in understanding Alzheimer’s. “More and more, people are paying attention to this,” Masdeu says. “They see, with so few options for treating Alzheimer’s disease, that is important.”

Sex Differences and Psychiatric Disorders

Significant differences often emerge between men and women in the prevalence, presentation, and progression of psychiatric disorders. Women are more likely to suffer from depression or an eating disorder. Men are more likely to be diagnosed with alcoholism or to commit suicide. Alzheimer’s, an irreversible and debilitating neurodegenerative disorder, is no different: Women are diagnosed more often and are more likely to exhibit signs of dementia than men who have the same level of Alzheimer’s pathology, the women’s health society wrote in its paper. And some of that disparity results from biological differences between women and men.

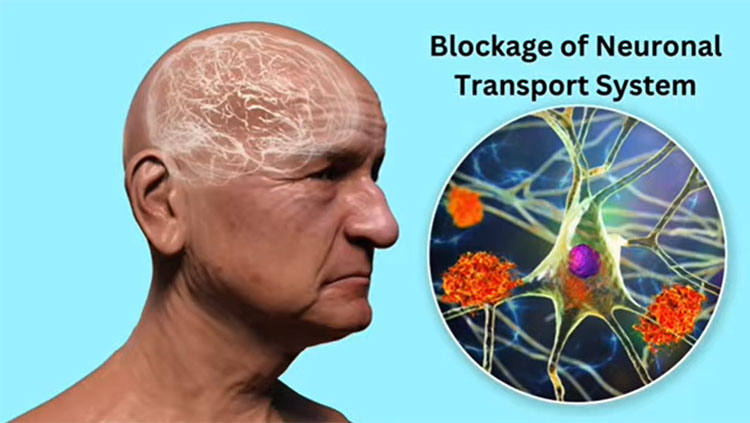

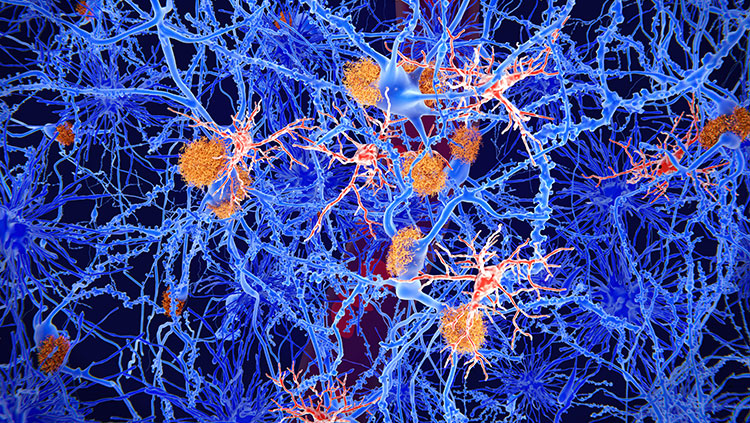

The most well-established genetic risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s is APOE e4, a variant of a gene called apolipoprotein E (APOE). Research shows that APOE e4 is a stronger risk factor in women than in men. Women with APOE e4 have more pronounced brain pathology than men, showing more dementia symptoms and more buildup of the sticky plaques called amyloid beta protein that are associated with the disease.

Understanding those differences in APOE e4 risk, Maki says, could lead to treatments that benefit both women and men.

APOE e4 is also associated with higher cholesterol levels and greater risk of heart disease, which raises questions about its role in causing Alzheimer’s. Maki wonders if men are dying from the cardiovascular effects of APOE e4, leaving women, who generally live longer, to be exposed to the cognitive effects of APOE e4 that manifests itself into Alzheimer’s. “These are mechanistic questions that cannot be teased out in research of human beings,” Maki says. Researchers cannot access the brains of live human patients to follow disease pathology — instead, they rely on animal models of disease. Yet, too many animal studies only use male animals. Even clinical trials for potential Alzheimer’s treatments may not investigate the differences between male and female responses to the drug being tested. Maki argues, this hinders our understanding of important sex differences in this disease.

The Challenges of Sex Differences Research

In 2014, the National Institutes of Health instituted new policies requiring that researchers focus on sex as a biological variable in future biomedical research programs funded by the agency after studies showed significant sex differences in treatment protocols for a variety of medical conditions. Masdeu, of Houston Methodist Hospital, says that clinical researchers should analyze data “considering both males and females, with animal models and during clinical trials for treatments.”

“We have to persevere and work toward the goal of expanding research to include both sexes."

But research on sex differences is expensive, says Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), who outside of her role at NIDA, recently collaborated on an Alzheimer’s-related study. “You often need double the sample size to meaningfully address differences between males and females,” Volkow says. “We have to persevere and work toward the goal of expanding research to include both sexes. And at the same time, we have to put the necessary resources and funding in place, so we can do it in a meaningful way.”

Masdeu says one way to help fill in some of the research gaps SWHR highlighted regarding sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease is to look at data from existing research studies. Enterprising researchers may find previously unexamined sex differences in these data sets.

“In many cases, the data is there,” Masdeu says. “Someone just has to look and see — whether it’s a study about sleep, or hormones, or inflammation, or any of the other factors we know may be involved in the development of Alzheimer’s disease — where sex may be important.”

That is certainly one approach, says Maki. But she and her colleagues with the SWHR hope the neuroscience community will also invest in new research programs that investigate important sex differences in this powerful and expensive disease. Maki says that while the SWHR talks about looking at pathology in women, the goal is to develop treatments for both sexes.

“This isn’t just women saying, ‘We need more research for us.’ On the contrary, sex differences research is research that benefits both sexes,” Maki says. “If more people can look at the different biological mechanisms underlying these sex differences we see in Alzheimer’s disease, we have more opportunity to find therapeutic targets that may be helpful to both men and women. That’s the whole point.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Clayton J. A., & Collins F. S. (2014). Policy: NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies. Nature, 509(7500) 282-283. doi: 10.1038/509282a

Nebel, R. A. Aggarwall, N. T, Barnes, L. L., Gallagher, A. Goldstein, J. M. . . . Maki, P. M. (2018). Understanding the Impact of sex and gender in Alzheimer’s disease: A call to action. Alzheimer’s Association, 14(9) 1171-11183. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.008

Also In Alzheimer's & Dementia

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org