When the Immune System Attacks the Brain

- Published16 Jan 2020

- Author Levi Gadye

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Neurologist Souhel Najjar isn’t unaccustomed to receiving phone calls from the families of psychiatric patients, but in 2016, he got a call that struck him with déjà vu.

“There was a patient who had been locked up in a psychiatric unit,” said Najjar. “She was put on all sorts of psychotropic drugs, catatonic, eyes closed, no verbal output, stiffness and rigidity throughout her body. Then her father, who is a physician, called me.”

The patient was Eileen Tchao, and things looked grim. Weeks earlier, the college senior was preparing to apply to law school. Now, she couldn’t even talk, and her doctors couldn’t help her.

Then, Tchao’s mother picked up a book, Brain on Fire, and began reading the story of journalist Susannah Cahalan. Cahalan had nearly died of a mysterious neurological disease in the late 2000s — and was saved by Najjar, who correctly diagnosed and cured her in the nick of time. Was Tchao suffering from the same disease?

Tchao’s father rang Najjar and explained how his daughter had descended through stages of what first looked like mood swings, then schizophrenia, then epilepsy. As a last resort, she had been treated with electroconvulsive therapy six times, to no avail.

The next morning, Najjar showed up at the psychiatric unit where Tchao was being held. After a taking a sample of her cerebrospinal fluid via a spinal tap, Najjar diagnosed her with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis — the very disease that had nearly killed Cahalan.

“With that call,” said Najjar, “Dr. Tchao saved his daughter’s life.”

For a neurological illness, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is quite the success story. Today, 75% of patients who are diagnosed and treated will recover completely, and 95% will survive.

BrainFacts.org spoke with Najjar, as well as fellow neurologist and expert in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis Joseph Masdeu about this disease, its history, and what it can teach us about the strange phenomenon when the immune system attacks the brain.

Discovery

In 2007, neurologist Josep Dalmau described a new disease, associated with a type of ovarian cancer, resembling both psychiatric and neurological illness. Neurological illnesses are usually traced to damage to the brain, while psychiatric illnesses usually entail problems with behavior and emotion; still, the two are not mutually exclusive.

Dalmau’s study detailed 12 cases of women between the ages of 14 and 44 who had been hospitalized for a confounding variety of symptoms.

Initially, these patients exhibited mood disturbances, like inappropriate bouts of laughing and crying, typical of psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar disorder. But soon, they developed amnesia, seizures, and even respiratory problems so severe doctors were forced to put the patients on ventilators. These kinds of symptoms are commonly encountered in neurological illnesses, like epilepsy, which can disrupt parts of the brain controlling vital bodily functions, like breathing.

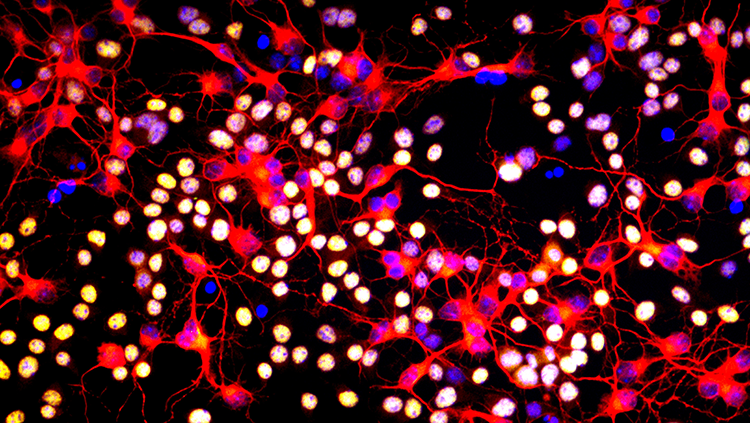

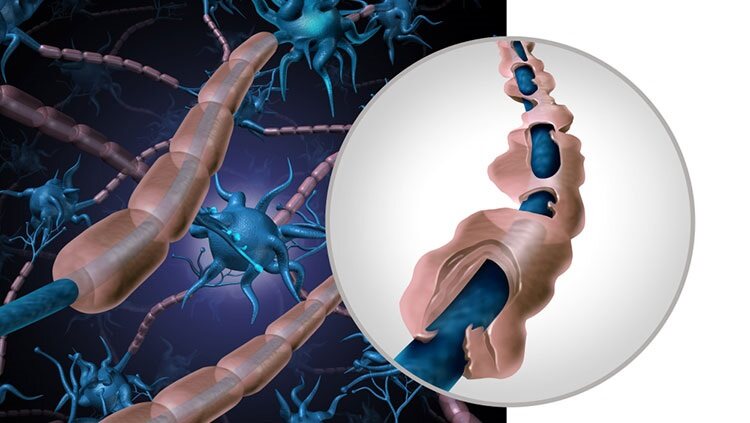

Dalmau discovered these patients’ immune systems had gone into overdrive, and inflammation was shutting down the brain. Specifically, the immune system was attacking a type of neurotransmitter receptor, the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, disrupting communication between neurons in the brain.

Typically, when a foreign threat, like a virus, enters the body, the immune system releases molecules, called antibodies, which stick to infected cells, flagging them for destruction. In most of the patients in Dalmau’s study, neurons possessing the NMDA receptor had grown in a benign ovarian tumor called a teratoma. In response, the immune system pounced, producing antibodies that stuck to NMDA receptors.

Then, somehow, this immunological war on NMDA receptors in the ovary spilled over to the NMDA receptors in the brain, shutting down important brain regions, like those responsible for learning, memory, and motor control.

Dalmau dubbed the disease anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, with “anti-NMDA receptor” referring to the antibodies, and “encephalitis” referring to brain inflammation.

By removing the ovarian teratomas and dampening inflammation using immune therapies, the disease could be cured in many of these early patients. But as the medical field began to note other cases of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, it became clear that ovarian teratomas were only part of the story.

A War With No Cause

When Najjar was called in to help Susannah Cahalan in 2009, he was primed to make the right diagnosis, after Cahalan’s doctors had failed to do so themselves.

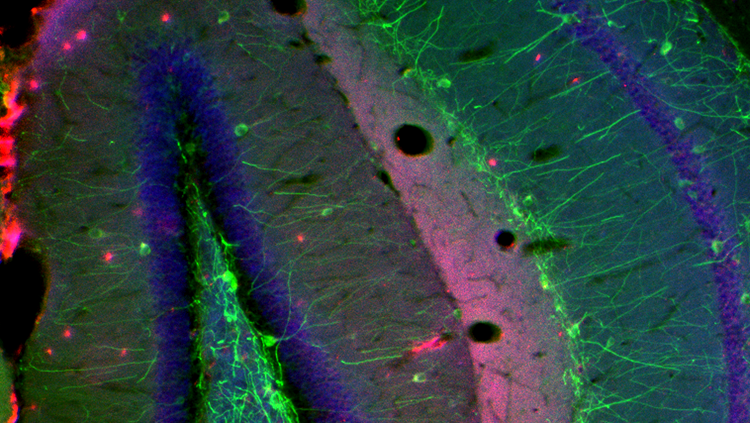

Decades prior, during Najjar’s training as a neuropathologist, he had observed inflammation in the post-mortem brains of psychiatric patients who had died by suicide. Crucially, such inflammation could only be observed by looking at brain samples under a microscope, because MRI scans can’t reveal details of the brain at the cellular level.

“As a neuropathologist, I was totally familiar with the concept that neuroinflammation can cause psychiatric illnesses, which can also escape neural imaging detection,” said Najjar. “In fact, 70% of patients with autoimmune encephalitis have normal brain MRIs, just like Cahalan.”

Two clues tipped off Najjar: an overabundance of white blood cells — the ground troops of the immune system — in a spinal tap, and Cahalan’s failure to accurately draw a clock, indicative of a neurological problem on one side of her brain.

Najjar confirmed his hunch with a brain biopsy, which proved, under the scrutiny of the microscope, that immune cells were attacking Cahalan’s brain. He immediately started Cahalan on drugs to calm her immune system, and meanwhile sent tissue samples to Dalmau, who had recently developed tests for this newfound disease.

Cahalan soon tested positive for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, making her the 217th patient to receive such a diagnosis. And, curiously, Cahalan did not have an ovarian teratoma, like half of the patients identified by Dalmau since the publication of his 2007 paper. Her immune system had inexplicably gone on a rampage against her brain — a war without a cause.

Defeating an Enigmatic Enemy

Thanks to the absence of ovarian teratomas in both cases, the root causes of Cahalan and Tchao’s respective bouts with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis remain a mystery. Yet the disease’s consequences are often, remarkably, reversible.

NMDA receptors normally sit on the outside of neurons, waiting to receive signals from other neurons. When antibodies stick to these receptors, the receptors are “internalized,” or sucked back inside, depriving those neurons of the ability to “hear” communication from the rest of the brain.

Importantly, though, “the neurons remain intact,” according to Masdeu, who has worked with Dalmau for nearly a decade to better treat and understand anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

“As soon as you lower the antibodies, those receptors come back up and the synapse becomes functional,” said Masdeu. “And these patients do quite well.”

The early symptoms of the disease, like “behavioral and mood changes, psychosis, seizures, and cognitive impairment,” seem to be caused by this receptor internalization, Najjar said, while the more dire symptoms that occur late in the disease, like respiratory failure, “we tend to believe are the result of secondary inflammation.”

These two aspects of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis determine, in part, successful treatment. The harmful antibodies can be flushed from the body using techniques like plasmapheresis, which filters antibodies out of the blood. Inflammation is countered using steroid drugs or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) therapy, which is a transfusion of purified antibodies in blood serum that “distracts” the immune system from attacking the brain. For severe cases, neurologists can also prescribe drugs to kill off the immune cells producing anti-NMDA receptor antibodies in the first place.

Masdeu and Najjar have each treated dozens of patients with the disease. But both clinicians are also keenly intrigued by the marked similarities between anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis and psychiatric illness and believe the disease may help break the détente that has long existed between incurable psychiatric illness and modern medicine.

A Window Into Psychiatric Illness

When Cahalan was first institutionalized, some of her doctors thought she had schizophrenia. As her condition deteriorated, it became clear this wasn’t the case.

Masdeu and Najjar repeatedly find anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis cases hiding within the population of patients incorrectly thought to have schizophrenia — and could benefit from treatment, if only they could be properly diagnosed.

“We are trying to perfect a method that will allow us to detect [these] antibodies in people with greater sensitivity,” said Masdeu. “If we find that even some of these schizophrenia patients do have antibodies, then we can cure them, which would be incredible.”

Despite increased awareness of the disease and its early detection, Najjar argues the field can do even better and need to continue to spread the knowledge among all healthcare professionals such as nursing staff and physicians of various specialties, particularly general neurologists, primary care physicians, and psychiatrists.

"If we find that even some of these schizophrenia patients do have antibodies, then we can cure them, which would be incredible."

The cross-talk between psychiatry and neurology that occurs with these patients has also provided tantalizing new leads for treating disease like schizophrenia, which currently must be managed, but cannot be cured.

One compelling line of reasoning suggests viral infections may both incite an immunological response, and, in some patients, inadvertently expose the brain to collateral damage.

“We are beginning to understand some of the causality of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis,” via decades of patient observation, said Masdeu. “For instance, people who get herpes encephalitis, in the aftermath, some of them get this kind of [psychiatric] problem.”

Indeed, Cahalan fell ill with flu-like symptoms — possibly caused by a virus — in the weeks before she was hospitalized with psychiatric symptoms, according to Najjar.

For an immune reaction to reach the brain though, antibodies must be able to cross the blood-brain barrier, which normally protects the spinal cord and brain from the impact of the immune system. Evidence from animal models of the disease suggests the blood-brain barrier must be breached for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis to occur, leading Najjar to speculate that “in some patients, a viral-like illness can open the blood-brain barrier, and allow antibodies to enter the brain.”

While the theory has yet to be proven in humans, it may someday help doctors unravel what’s going on in a variety of psychiatric illnesses. Though the pieces of the puzzle haven’t produced a coherent picture of what causes schizophrenia, the field is warming up to the idea that psychiatric illness may, generally, relate to the immune system.

For now, Najjar and Masdeu are continuing to identify patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis within the much larger population of psychiatric patients and are hopeful about future collaborations between psychiatry and neurology.

“Both specialties take care of these patients, and we are fine,” said Masdeu. “Working together, these two specialties can do a very good job, and give these patients the opportunity to regain their lives.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Discussion Questions

1) What symptoms did Susannah Cahalan and Eileen Tchao have in common in their cases of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis?

2) What did Josep Dalmau’s 2007 study find and how did the antibodies cause disruption in neuron communication?

3) What implications does the treatment of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis have for the future study of psychiatric illness and the immune system?

References

Dalmau, J., Tüzün, E., Wu, H., Masjuan, J., Rossi, J. E., Voloschin, A., … Lynch, D. R. (2007). Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Annals of Neurology, 61(1), 25–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.21050

Masdeu, J. C., Dalmau, J., & Berman, K. F. (2016). NMDA Receptor Internalization by Autoantibodies: A Reversible Mechanism Underlying Psychosis? Trends in Neurosciences, 39(5), 300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.02.006

Also In Immune System Disorders

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org