Multiple Sclerosis: When the Immune System Attacks the Nervous System

- Reviewed21 Aug 2023

- Author Gail Zyla

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

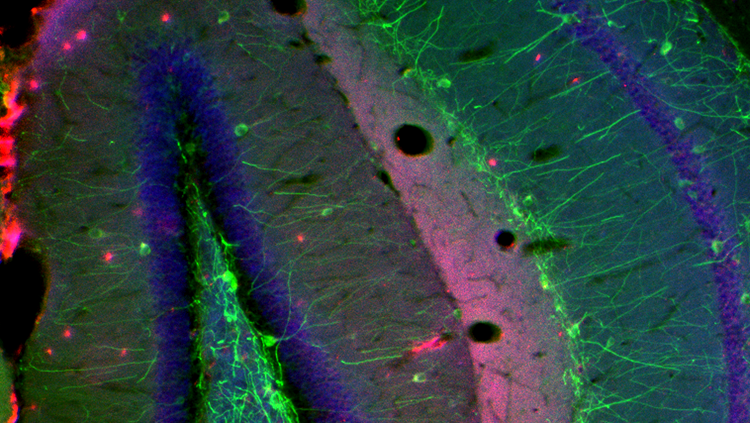

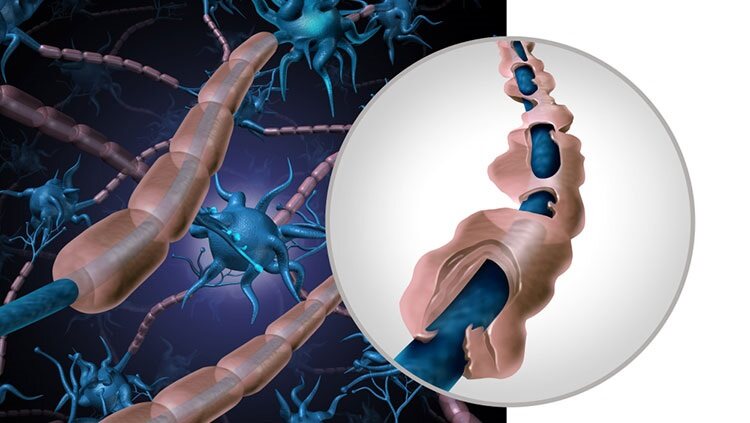

As of 2023, 2.9 million people around the world live with multiple sclerosis (MS): an inflammatory, autoimmune disease of the central nervous system commonly diagnosed in people between 20 and 40 years of age. For unknown reasons, the immune system of a person with MS launches an attack against its own central nervous system, including the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves. The target of this attack is the myelin, a fatty substance that forms a protective coating around nerve fibers; the nerve fibers themselves can also be affected. As a result of the attack, the damaged myelin sheath and accompanying inflammatory cells form lesions, patches of scar tissue that look like sclerosis.

In MS, the patches of disease activity appear in multiple areas of the central nervous system, which is why the disease is called multiple sclerosis. Damage to the myelin sheaths and nerve fibers interferes with transmission of nerve impulses within the brain and spinal cord, as well as their communication with other body areas. The effects of MS are often compared to the loss of insulation around an electrical wire and damage to the wire itself, interfering with signal transmission. Damage can occur in the white (myelin) and gray (nerve cell bodies, glia, etc.) matter of the brain.

Damage to the nervous system in people with MS can cause a wide array of symptoms. The spinal cord, cerebellum, and optic nerve are commonly affected by MS, so problems often arise in functions controlled by those areas. Symptoms include numbness, clumsiness, and blurred vision. Other symptoms are slurred speech, weakness, pain, loss of coordination, uncontrollable tremors, loss of bladder control, memory loss, depression, and fatigue.

The cause of MS is unknown, but there are some hints that genetic factors, environmental factors, and certain viruses are involved. Siblings of people with MS are 10 to 15 times more likely to develop MS than people with no family history of the disease. The risk is particularly high for an identical twin of someone with MS. Oddly, the disease is more prevalent in temperate climates, such as the northern United States and northern Europe, than in the tropics. Although Caucasians run a higher risk than other races of developing MS, the prevalence of MS indicates that risk is shaped by both genetic and geographical factors. Several studies have shown that those who spend more time in the sun and have relatively higher levels of vitamin D are less likely to develop MS, possibly through UV light’s impact on the immune system and through vitamin D’s impacts on immune system regulation.

Additionally, people who develop an exaggerated immune response to certain viruses like the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) — the virus that can cause infectious mononucleosis, or mono — may have a higher likelihood of developing MS in the future. Although EBV eventually infects around 95% of adults, very few will develop MS.

When a person is diagnosed with MS, treatment options depend on the type of disease that is present. Specialists classify MS as one of four categories:

- clinically isolated syndrome, referring to a first episode of neurologic symptoms caused by inflammation and demyelination;

- relapsing-remitting MS, characterized by flare-ups of new or worsening symptoms followed by complete or partial remission of symptoms;

- primary-progressive MS, defined by progressive worsening of symptoms after disease onset;

- and secondary-progressive MS, in which relapsing-remitting disease has transitioned into a progressive form of disease that worsens over time.

Within each of the three latter categories, MS is further classified as “active” or “not active.” While the categories refer to the progression of symptoms, this classification refers to presence (“active”) or absence (“not active”) of a clinical relapse or new areas of inflammation that can be seen on MRI scans. In some cases, MS is defined as “stable,” meaning that symptoms are stable, and no activity appears on routine MRI scans.

MS has no cure, but an increasing number of medications are becoming available or are under investigation. Several medications help control the inflammation and immune system attacks in relapsing-remitting MS with variable response rate. Some medications are highly effective in controlling inflammation but are less effective in controlling disease progression. Steroid drugs, specifically glucocorticoids, reduce the inflammation and might also help shorten acute attacks. Medications and therapies are also available to control symptoms such as muscle stiffness, pain, fatigue, mood swings, and bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction.

Adapted from the 8th edition of Brain Facts by Gail Zyla.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

AIDS and HIV, Neurological Complications of. (2023). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/aids-and-hiv-neurological-complications

Bang, O. Y., Kim, E. H., Cha, J. M., & Moon, G. J. (2016). Adult Stem Cell Therapy for Stroke: Challenges and Progress. Journal of stroke, 18(3), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2016.01263

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). HIV in the United States and Dependent Areas. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Stroke Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Traumatic Brain Injury & Concussion. https://www.cdc.gov/TraumaticBrainInjury/

Chapman, S. N., Mehndiratta, P., Johansen, M. C., McMurry, T. L., Johnston, K. C., & Southerland, A. M. (2014). Current perspectives on the use of intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) for treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Vascular health and risk management, 10, 75–87. https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S39213

Correale, J., Gaitán, M. I., Ysrraelit, M. C., & Fiol, M. P. (2017). Progressive multiple sclerosis: from pathogenic mechanisms to treatment. Brain : a journal of neurology, 140(3), 527–546. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aww258

Doulames, V. M., & Plant, G. W. (2016). Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Therapies for Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. International journal of molecular sciences, 17(4), 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17040530

Gereau, R. W., 4th, Sluka, K. A., Maixner, W., Savage, S. R., Price, T. J., Murinson, B. B., Sullivan, M. D., & Fillingim, R. B. (2014). A pain research agenda for the 21st century. The journal of pain, 15(12), 1203–1214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2014.09.004

Global HIV & AIDS Statistics — Fact Sheet. (2022). UNAIDS. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

HIV and AIDS Dementia. (2023). WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/dementia-hiv-infection

Frysh, P. (2022). HIV Neuropathy: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/hiv-neuropathy-symptoms-causes-treatment

Krieger S. C. (2016). New Approaches to the Diagnosis, Clinical Course, and Goals of Therapy in Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.), 22(3), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1212/CON.0000000000000324

Martucci, K. T., Ng, P., & Mackey, S. (2014). Neuroimaging chronic pain: what have we learned and where are we going?. Future neurology, 9(6), 615–626. https://doi.org/10.2217/FNL.14.57

Matinella, A., Lanzafame, M., Bonometti, M. A., Gajofatto, A., Concia, E., Vento, S., Monaco, S., & Ferrari, S. (2015). Neurological complications of HIV infection in pre-HAART and HAART era: a retrospective study. Journal of neurology, 262(5), 1317–1327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-015-7713-8

National Cancer Institute. (2017). Cancer Stat Facts: Brain and Other Nervous System Cancer. NIH. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/brain.html

National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. (2017). University of Alabama at Birmingham. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/

Okura, H., Smith, C. A., & Rutka, J. T. (2014). Gene therapy for malignant glioma. Molecular and cellular therapies, 2, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-8426-2-21

Origin of HIV and AIDS. (2022). Be in the KNOW. https://www.beintheknow.org/understanding-hiv-epidemic/context/origin-hiv-and-aids

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). (2022). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html

Reardon, D. A., Freeman, G., Wu, C., Chiocca, E. A., Wucherpfennig, K. W., Wen, P. Y., Fritsch, E. F., Curry, W. T., Jr, Sampson, J. H., & Dranoff, G. (2014). Immunotherapy advances for glioblastoma. Neuro-oncology, 16(11), 1441–1458. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nou212

Rosado, I. R., Lavor, M. S., Alves, E. G., Fukushima, F. B., Oliveira, K. M., Silva, C. M., Caldeira, F. M., Costa, P. M., & Melo, E. G. (2014). Effects of methylprednisolone, dantrolene, and their combination on experimental spinal cord injury. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology, 7(8), 4617–4626. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4152024/

Schonberg, D. L., Lubelski, D., Miller, T. E., & Rich, J. N. (2014). Brain tumor stem cells: Molecular characteristics and their impact on therapy. Molecular aspects of medicine, 39, 82–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2013.06.004

Schulenburg, A., Blatt, K., Cerny-Reiterer, S., Sadovnik, I., Herrmann, H., Marian, B., Grunt, T. W., Zielinski, C. C., & Valent, P. (2015). Cancer stem cells in basic science and in translational oncology: can we translate into clinical application?. Journal of hematology & oncology, 8, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-015-0113-9

Simons, L. E., & Basch, M. C. (2016). State of the art in biobehavioral approaches to the management of chronic pain in childhood. Pain management, 6(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt.15.59

Simons, L. E., Elman, I., & Borsook, D. (2014). Psychological processing in chronic pain: a neural systems approach. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 39, 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.12.006

Stuckey, D. W., & Shah, K. (2014). Stem cell-based therapies for cancer treatment: separating hope from hype. Nature reviews. Cancer, 14(10), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3798

Su, Y. S., Ali, R., Feroze, A. H., Li, G., Lawton, M. T., & Choudhri, O. (2016). Endovascular therapies for malignant gliomas: Challenges and the future. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia, 26, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2015.10.019

Understanding the HIV Epidemic. (2017). Be in the KNOW. https://www.beintheknow.org/understanding-hiv-epidemic/data

Wang, S. X., Ho, E. L., Grill, M., Lee, E., Peterson, J., Robertson, K., Fuchs, D., Sinclair, E., Price, R. W., & Spudich, S. (2014). Peripheral neuropathy in primary HIV infection associates with systemic and central nervous system immune activation. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 66(3), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000167

White, H. & Venkatesh, B. (2016). Traumatic brain injury. Oxford Textbook of Neurocritical Care, 17. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=o7hlCwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA210&dq=traumatic+brain+injury&ots=53PDiF2Jhx&sig=TPqEUTtTpGBJdRxBbZPcgO1pqpc#v=onepage&q=traumatic%20brain%20injury&f=false

Zenebe, Y., Necho, M., Yimam, W., & Akele, B. (2022). Worldwide Occurrence of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders and Its Associated Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 814362. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.814362

What to Read Next

Also In Immune System Disorders

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org