Aging with COVID-19: Post-Infection Risks for Dementia

- Published17 Jan 2023

- Author Christine Won

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

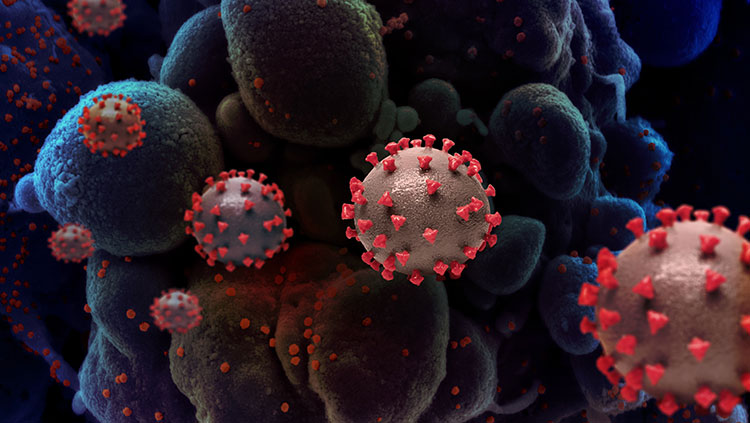

An estimated 3.39 billion people, over 40% of the world's population, have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 at least once as of November 2021, according to the medical journal The Lancet. Even though most have largely recovered from the infection that has killed over 6 million, the full long-term effects of COVID-19 remain unknown.

“This isn’t the first time that a flu-like viral infection has been linked to an increased risk for dementia,” says Robyn Klein, director of the Center for Neuroimmunology & Neuroinfectious Diseases at Washington University School of Medicine, the moderator for the COVID-19 press conference at Neuroscience 2022, the Society for Neuroscience’s annual meeting. “But one of the most important aspects of this work is the magnitude of people potentially affected by this — millions upon millions.”

"We're interested in what happens in the decades to come — there’s so very many people who have recovered from COVID. And this is laid on top of an aging population already with a predicted surge in Alzheimer’s disease. How is COVID going to alter long-term dementia risk?”

Researchers examining the role of inflammation in COVID-19 raise an important question: Will COVID-19 infections lead to a surge in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias?

“We're interested in what happens in the decades to come — there’s so very many people who have recovered from COVID,” says Natalie Tronson of the University of Michigan and senior author of the study on the inflammatory effects of COVID-19. “And this is laid on top of an aging population already with a predicted surge in Alzheimer’s disease. How is COVID going to alter long-term dementia risk?”

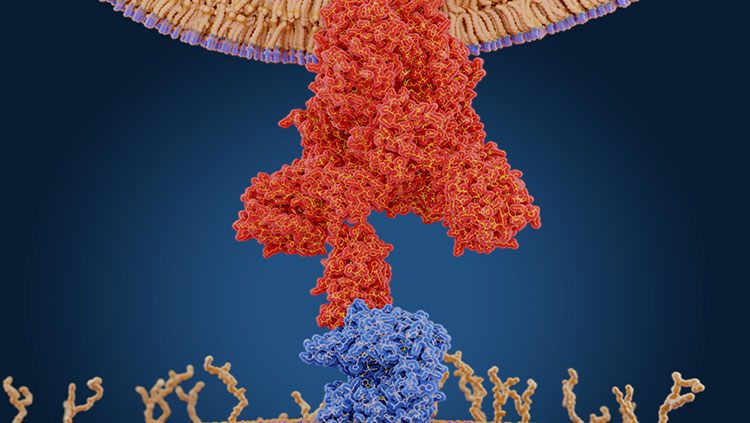

Tronson and colleagues found a two-week immune challenge mimicking COVID-19-like inflammation in mice caused memory deficits that persisted for months. Specifically, they looked at the role of inflammation in these memory impairments that exist long after recovery from illnesses. To do so, they used injections of the antiviral R848 resiquimod, which activates the same innate immune system component (toll-like receptor-7) as SARS-CoV-2.

After eight weeks, the researchers tested the mice’s long-term memory in two ways: novel object recognition and context fear conditioning. In the novel object recognition test, mice explore two identical objects before the researchers switch one out. If the mice remember the item, the hypothesis is they will spend more time exploring the new item because mice are curious, exploratory creatures. In the study, control mice demonstrated a clear preference for the novel object, compared with R848 mice, which showed less interest.

Context fear conditioning is similar to classic Pavlovian testing, in which scientist Ivan Pavlov demonstrated dogs could be trained to start drooling at the ring of a bell if it is repeatedly rung at every mealtime so they learn to associate the sound with food.

For their study, Tronson and colleagues used a context or testing box in which mice were given a brief, mild foot shock after they explored the box. When they placed the mice back in the same box the next day, mice who remembered the shock demonstrated various fearful and defensive behaviors, including what is known as “freezing,” a commonly measured behavior in mice as an index of fear. Fear conditioning is a more “robust” form of memory test because quickly adapting to danger is directly linked to survivability.

Interestingly, Tronson’s team found a decreased response in young adult females and mid-aged males, though not consistently across all study groups, “suggesting a role [for] age and sex interactions in vulnerability to memory deficits as well,” says Tronson. “What’s important is that this is happening eight weeks later,” she says, adding memory deficits were persisting well after inflammation had resolved, as demonstrated by tests showing cytokine levels had returned to normal.

“Our study suggests having had a past COVID infection is likely a risk factor for cognitive decline during aging,” says Amy Choi, research associate in Tronson’s lab and the study’s first author. Next, the team wants to discover whether the process is reversible and if they can target specific mechanisms “to prevent pandemic-related increased risk [for dementia] in the decades to come.”

According to Tronson, the biggest takeaway from their study is that it’s not just the virus we have to worry about, but also our bodies’ inflammatory response to COVID-19. “It’s not going to cause us all to get dementia. But it might accelerate the risk,” Tronson says. “Our next questions are, how do we prevent it?”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Also In COVID-19

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org