Primate Research Labs: The Other Frontline of the Pandemic

- Published20 Jul 2021

- Author Calli McMurray

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States, organizations and businesses on the front lines transformed almost overnight. Government officials set up testing sites in parking lots. Grocery store employees erected plastic barriers and plastered the floor with tape to mark out six feet of social distance in aisles. Hospitals shuffled beds and supplies to create COVID-19 wards.

Another group of workers weathered the front line of the pandemic out of public sight: scientists at primate research centers. The United States houses 22,000 monkeys across a network of seven National Primate Research Centers. As the pandemic swept across the country, the primate research centers dropped everything to begin researching the coronavirus.

John Morrison, professor of neurology at the University of California Davis School of Medicine and director of the California National Primate Research Center, runs a lab studying monkey models of Alzheimer’s disease and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. In the first week of March 2020, Morrison’s lab had just begun new projects when he received some startling news about the coronavirus. “I was listening to our infectious disease specialists, and they were saying, ‘This is not going away. This is going to be a full-blown pandemic,’” Morrison says.

Bring in the Monkeys

He had four priorities to address immediately: protect his staff, protect the monkey colony, slow down ongoing research, and begin COVID-19 research. “NIH [National Institutes of Health] came to us very early and said they were going to make [grant] supplements available, and they wanted us to develop a rhesus monkey model.”

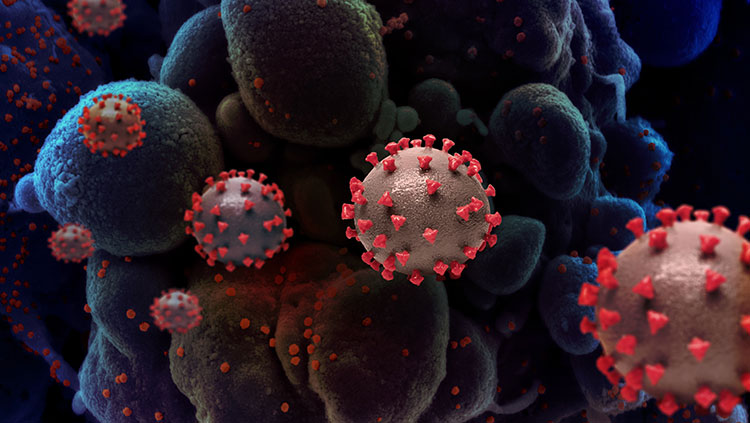

A robust monkey model is a critical first step for understanding what the coronavirus does to its host and how. “Monkeys tend to react to these viruses in a manner very similar to humans,” Morrison says. “That's not true of other animal models.” Studying the monkey model of COVID-19 would allow scientists to understand how the virus works, which body systems it affects, and how it impacts different age groups. Plus, monkey models receive the first round of tests for treatments and vaccines, which makes it safe for human clinical trials to begin.

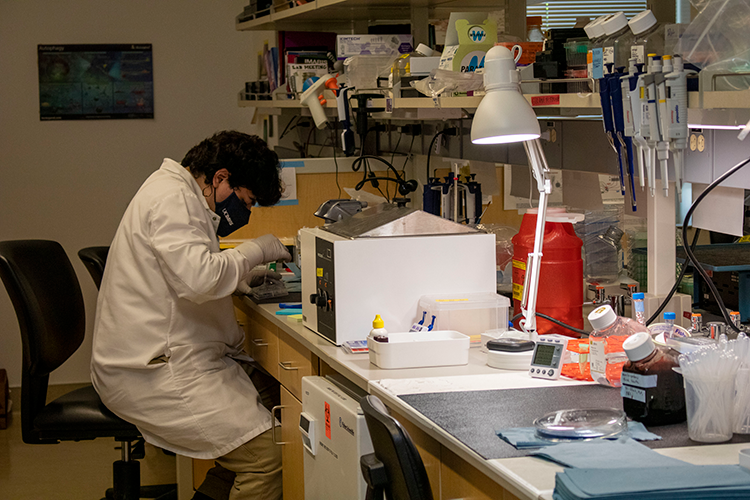

But setting up this type of research is difficult. Working with airborne microbes like the coronavirus requires Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) conditions in the lab, a high level of containment and safety. “Everything's harder, and everything takes longer in a BSL-3 facility,” Morrison says. The research staff completed extensive training and wore cumbersome protective equipment. The monkeys involved in experiments had to be housed in their own secure enclosure to protect the rest of the colony from infection. Staff also tested the colony for COVID-19 each week — not an easy task when you have a colony of 4,200 monkeys.

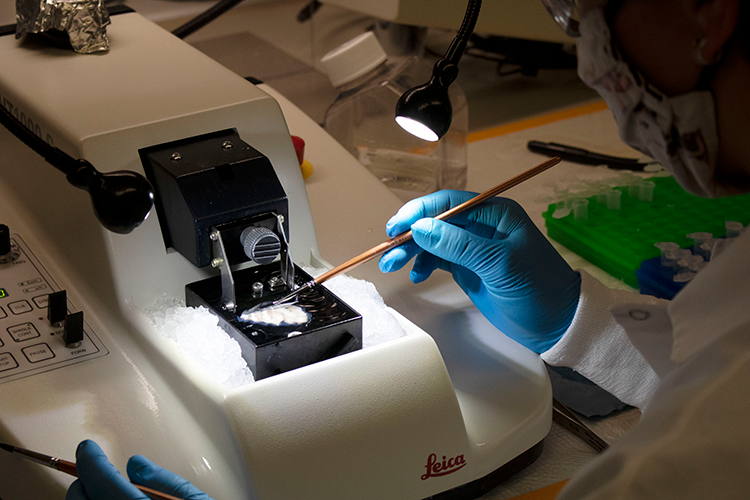

Each study entailed tracking the monkeys’ symptoms for 7 to 14 days as the virus ran its course — which is not as simple as it sounds. “You have to monitor the monkeys essentially 24 hours a day,” Morrison says, and the center was operating with only 50% of its staff. “So, a given study goes fairly quickly, but there's so much involved in each study in terms of all the endpoints that you want to measure.” This includes things like the viral load — a measurement of the intensity of infection — and biomarkers in plasma and cerebral spinal fluid.

The Trade-Off

This level of intensity and speed does not come without a cost. To accommodate the COVID-19 studies, the center slowed down and postponed other studies — sometimes for an entire year. The Alzheimer’s disease research pushed to the back burner still mattered, but Morrison’s lab made some tough decisions. “Of course, we had to put COVID at a high priority, but is COVID ever really a higher priority than Alzheimer's disease?” Morrison says. “That's a tough question to answer.”

Deliberations over which studies to delay or minimize took place in tandem with the start of the COVID-19 studies. “The labor force is being drawn in many different directions, and some of them are getting sick [with COVID-19],” Morrison says. “Almost on a daily level, we had to review everything that was going on and determine what could continue, what couldn't, what could be started, and what shouldn't be started.”

The round-the-clock work and immense pressure weighed on Morrison’s staff. “They had these demands at work and these demands at home, and it was often very difficult to satisfy both sets of demands,” Morrison says. For postdoctoral researcher Danielle Beckman, the COVID-19 research posed a heightened risk. “I have an autoimmune disease and take medication that suppresses my immune system,” Beckman says. Every time she went into the lab, she worried about catching the virus.

The research also took an emotional toll. Outside of work, Beckman kept tabs on the pandemic in the U.S. and in Brazil, where her family lives. “I couldn’t see my family, but [when you come into lab] you have to concentrate and have the mindset to do your research,” she says. This became increasingly difficult when her research echoed her life. “In the beginning, I was feeling a little uncomfortable because, unfortunately, my grandma in Brazil passed away from a stroke [related to COVID-19 infection]," Beckman says. “I was looking and seeing the same [effects] in my monkeys’ brains … It was very intense, a lot of emotions.”

But the center carried on. Lab members continued their original research, developed the COVID-19 monkey model, tested therapeutics, and ensured the virus did not spread among the colony. They even managed to publish a paper on an Alzheimer’s disease monkey model — one of the studies they were forced to slow down. “There was an incredibly strong sense of teamwork and incredibly strong sense that we're doing something — it's hard, what we're trying to do, but we're in there,” Morrison says. “We're in the fight; we're helping.”

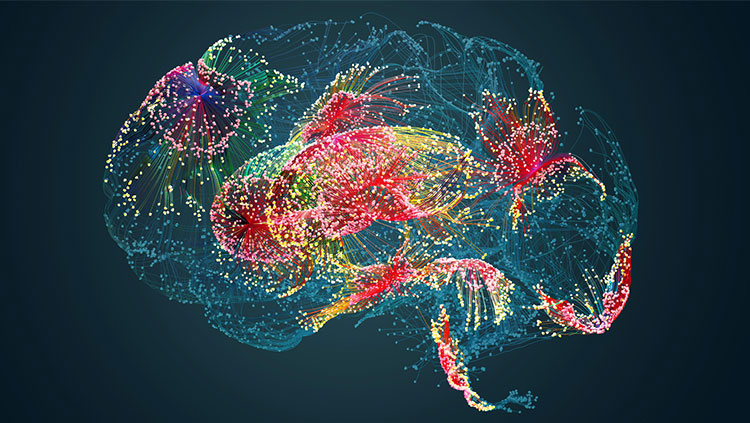

Waiting in the Wings

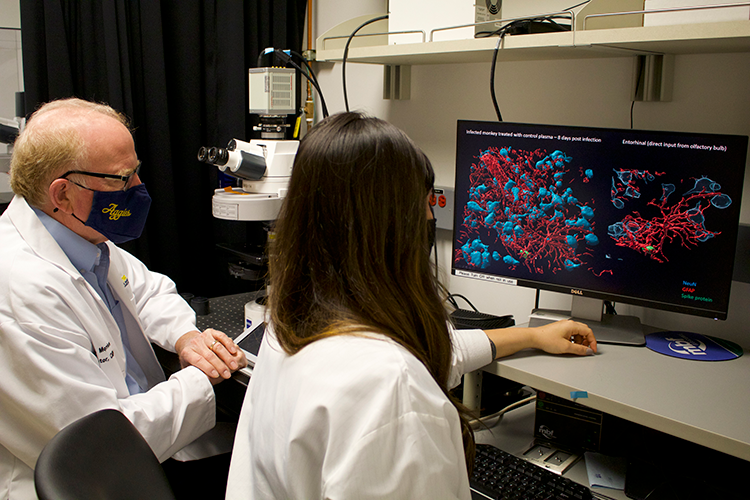

And the fight continues: after six months of studies, Morrison and his team have an abundance of data to analyze, including 50 monkey brains. The data should reveal more about how COVID-19 impacts the brain. “[Now] there's a new line of research in my lab, which is the interface between infectious disease and neuroscience, centered right now on COVID,” Morrison says. “We'll continue that area of research because I think it’s going to become one of the most important areas of neuroscience.”

After examining brains infected with COVID-19, Beckman decided to pivot her career in this new direction. “I'm so shocked with how viruses are getting into the brain and doing so much damage,” she says. “I learned during my PhD that the brain is immunoprivileged; viruses don't reach the brain that much. And when they do reach it, there's a lot of support from the immune cells. But this is not what we are seeing.”

Even once the COVID-19 pandemic ends, the work is far from over. The difficulties of the past year illuminated what science needs to do to remain agile and flexible, ready to address public health needs as they arise. “There's a lot of interest, both from the primate centers and from NIH, in making sure we're ready for the next pandemic so we can initiate the nonhuman primate work immediately,” Morrison says. “Because there will be another one, there's no question about that. It's just a matter of when and how severe.” And when the next pandemic does happen, Morrison remains confident the nation’s primate research centers will be ready to do their part to help defeat it.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Science Safety Security – Finding the Balance Together. phe.gov. (n.d.). https://www.phe.gov/s3/BioriskManagement/biocontainment/Pages/BSL-Requirements.aspx.

About Us. California National Primate Research Center. (2017, November 16). https://cnprc.ucdavis.edu/about-us/.

Also In COVID-19

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org