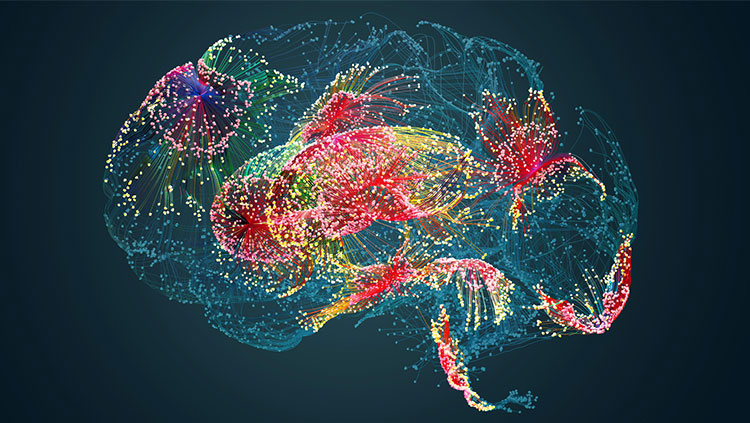

The respiratory illness COVID-19 causes neurological symptoms in more than one-third of patients, ranging from loss of taste and smell to disorientation and movement disorders.

The coronavirus may enter the brain through the olfactory nerve in the nose or by crossing the protective blood-brain barrier.

This video is from the 2020 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

Created by Swathi Pavuluri

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues around the world, it’s important to consider the various mechanisms by which this virus can affect us.

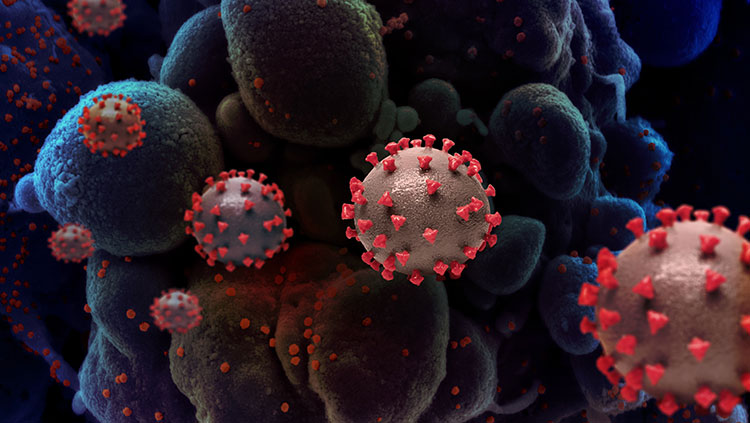

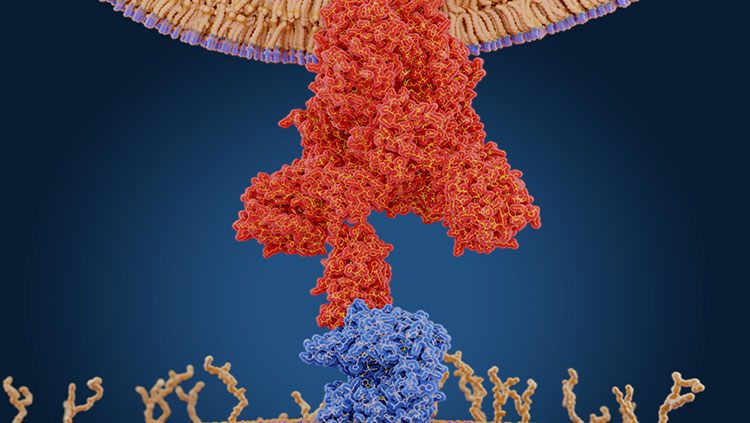

Like any other virus, the coronavirus infects the body by entering healthy cells to use them as a host for genome replication. It specifically uses the ACE2 receptor protein found on cells, especially epithelial cells in the respiratory tract. This allows it easy access to the respiratory tract lining and, most abundantly, the type II alveolar cells of the lungs.

Since it’s a respiratory disease, the usual symptoms observed from coronavirus, aside from fever and aches, include sore throat, cough, shortness of breath, and respiratory distress.

Emerging studies, however, point to the presence of neurological symptoms as well in over one third of coronavirus patients. Patients of various levels of coronavirus exhibit these neurological symptoms. Effects seen in milder cases and especially in young people include headaches, dizziness, brain inflammation, and strokes.

These particular symptoms have primarily been observed to be the outcome of robust immune responses that inadvertently result in the targeting of nerve cells. This can produce the unintentional inflammation or death of neurons. For example, Guillain-Barre syndrome, a neurological disorder that causes neurons to mistakenly be attacked by the immune system, has been associated with coronavirus, and can result in neuronal death as well as side effects such as pain and neural inflammation, which cause some of the other symptoms mentioned.

In more severe cases of coronavirus, neurological symptoms are more common with anywhere from 46 to 84% of patients in such cases exhibiting them. These patients can not only experience milder neurological effects, but also experience muscle weakness, loss of senses—specifically smell and taste—, strokes, seizures, and hallucinations. These symptoms are usually transient, but some patients have experienced symptoms such as disorientation, inattention, and movement disorders that persist even after coronavirus treatment and recovery.

Patients who experience more severe effects display infected neurons in addition to respiratory cells, indicating that the virus has somehow directly reached the brain. The brain also contains the ACE2 receptor that the coronavirus targets, but what isn’t completely clear is how the virus travels from the cells in the respiratory tract to those in the brain.

While not much is currently known about the exact means by which the virus can enter the brain, there are two major theories about the mechanisms by which this can take place. The first explanation is through the nose. Since the olfactory nerve is the only cranial nerve exposed to the outside world, the associated neurons might act as carriers for the virus. Infection of the olfactory neurons in the nose might actually serve as a connector that enables the coronavirus to spread directly from the respiratory tract to the brain. This could also explain the loss of smell and taste that have been reported in certain patients. And, from the method of nasal swabbing used to test for the virus, we do know that the virus is somehow housed in the nose.

The second explanation is that the virus could also spread through the blood to reach the brain. The ACE2 receptor that the coronavirus targets can also be found on endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. Thus, the virus may be able to travel through the blood to reach and cross the blood-brain barrier to arrive at the brain.

These two proposed mechanisms, in addition to the effects of a robust immune system response, can lead to the neurological symptoms, both milder and more severe, that have emerged among many coronavirus patients. As a result of all three of these factors, coronavirus may be one of the most blood clotting disorders ever seen. In fact, according to a professor at Hofstra medical school, "The risk of blood clots [is] anywhere from about three- to six-fold more than we're used to seeing." Thus, the risk of stroke is much higher among coronavirus patients, especially those of higher age or with any underlying cardiovascular factors.

A number of organizations are continuing to work toward aiding those affected by COVID-19. Consider checking out or contributing to any of these causes that you may be interested in, whether it's donating toward coronavirus research or relief, or using and sharing important hotlines and free mental health testing resources during these trying times.

Also In COVID-19

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org