Pesticides, Infections, and the Hunt for the Causes Behind Autism

- Published25 May 2017

- Reviewed25 May 2017

- Author Teal Burrell

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

In 1998, British physician Andrew Wakefield and his colleagues published a study in the journal The Lancet linking autism with a childhood vaccination. The finding terrified parents and contributed to families choosing to forgo vaccination with the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR). Even though Wakefield’s work and his assertions have been thoroughly debunked as fraud and the paper ultimately retracted, millions of people around the world continue to believe vaccines can cause autism.

In 2012, an estimated one in 68 children in the U.S. was diagnosed with autism.

Such persistent belief arises in part because of the dramatic increase in the number of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder over the past 15 years. In 2000, an estimated one in 150 children received an autism diagnosis; by 2012, that rate hit one in 68 in the U.S. Physicians have gotten better at recognizing the early symptoms of autism like social and communications problems; but, better detection can’t account for the entire increase. Genetic factors contribute to the risk of autism as well, but, again, genes don’t change enough in twelve years to explain the rise either.

However, current work implicates pesticide exposure and infection as two likely environmental culprits, and neuroscientists are teasing out how such exposures — especially when they occur before birth — may play a role in autism.

Pesticide Problems

When it comes to a link between prenatal exposure to pesticides and autism, organophosphate pesticides, such as chlorpyrifos, appear particularly suspect. In the U.S., organophosphates represent nearly 70 percent of pesticides used. They work by shutting down an enzyme vital to the function of insect nerves. That enzyme is also critical for human nerve function.

A 2014 study of pregnant women living within one mile of fields sprayed with organophosphates indicated these women were two times more likely to have a child with autism than women who didn’t live near the fields. The risk increased to three times greater for women living near fields treated with chlorpyrifos (known by trade names Dursban and Lorsban, among others).

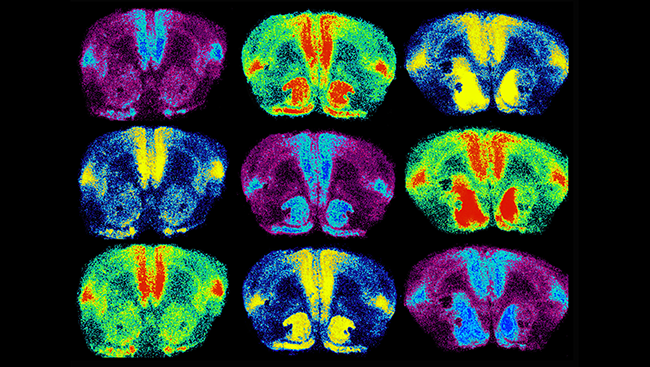

Jill Silverman at the University of California, Davis, explored the relationship between chlorpyrifos and autism in a rat model. Rat development differs from humans in one key way: the first few days after birth for a rat correlates to the third trimester in utero for a human. Silverman exposed newly-born rats to a low dose of chlorpyrifos and compared them to a group of rats exposed to a control substance during the same developmental period. As pups, the chlorpyrifos-exposed rats made fewer calls to their mothers than control-treated pups, and, when they grew up, chlorpyrifos-exposed rats played less with other rats.

“We found that the early life exposure to chlorpyrifos affected not just one developmental behavior relevant to autism but two, both communication and social behavior,” says Silverman.

Infection’s Impact

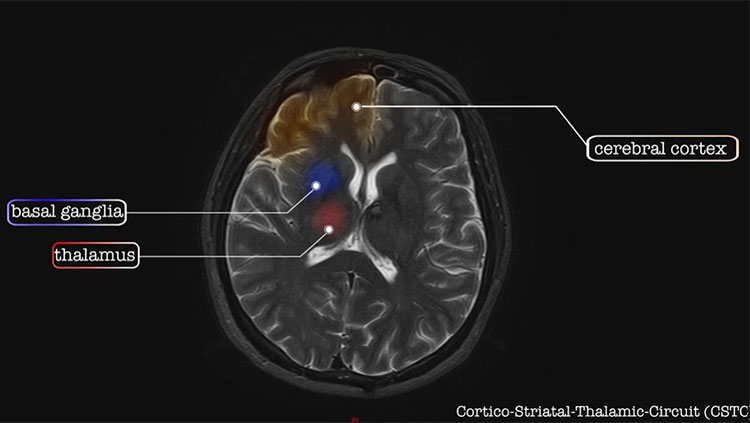

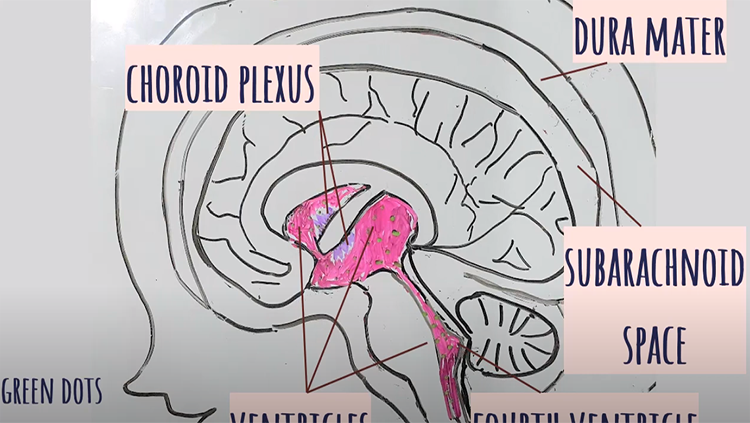

Starting in the early 1970s, researchers began linking serious infection during pregnancy to an increased risk of having a child with autism. A Swedish study examining every individual born in the country from 1984 2007 showed that pregnant women who had been hospitalized for an infection — whether viral, bacterial, or from unknown causes — were 30 percent more likely to have a child with autism than pregnant women who didn’t suffer from a serious infection. Scientists speculate that infection ramps up the woman’s immune system, causing excessive inflammation in the fetal brain and disrupting development.

Research with mouse models supports that the theory. When scientists trigger inflammation in pregnant mice, their pups display social impairments similar to autism. For example, when given a choice, mice typically opt to hang out with the other mice rather than focus on an inanimate object. However, mice exposed to inflammation prenatally spend as much time with an object as with another mouse.

As researchers continue to delve into environmental risk factors for autism, it’s becoming clear that the environment, genetics, and timing may all interact to produce autism; pesticide exposure or an infection during pregnancy might exacerbate a genetic susceptibility. “The overall message is that it’s very important that we look at environmental risk factors as well and in combination with genetics,” says Silverman.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Autism Spectrum Disorder Data and Statistics

Gregory SG, Anthopolos R, Osgood CE, et al. Association of autism with induced or augmented childbirth in North Carolina birth record (1990-1998) and education research (1997-2007) databases. JAMA Pediatrics, 167: 959-966 (2013).

Hertz-Picciotto I & Delwiche L. The rise of autism and the role of age at diagnosis.Epidemiology, 20: 84-90 (2009).

Kenkel W. Treating pregnant prairie voles with oxytocin influences offspring’s social development. Press conference at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience (2016).

Lee BK, Magnusson C, Gardner RM, et al. Maternal hospitalization with infection during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders.Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 44: 100-105 (2015).

Minakova E. Medication reduces social deficits in mouse model of autism. Press conference at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience (2016).

Shelton JF, Geraghty EM, Tancredi DJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental disorders and prenatal residential proximity to agricultural pesticides: the CHARGE study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122: 1103-1109 (2014).

Silverman J. Exposure to low dose of common pesticide disrupts neurological development in rats.Press conference at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience (2016).

Also In Childhood Disorders

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org