Addiction: Can the Brain Control Our Uncontrollable Urges?

- Published26 Feb 2014

- Reviewed26 Feb 2014

- Source The Kavli Foundation

Earlier this year, the Commission on Narcotic Drugs, part of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, convened a meeting in Vienna, where a group of scientists recommended to the commission that the problem of substance use disorders—a term that refers to what most people think of as addiction—should be approached as a medical, and not a legal, issue. What have scientists discovered about addiction that led them to consider it as a disease rather than due to users’ lack of willpower? And if addiction is a disease, can it be managed like other diseases, or does it require an entirely new approach?

These also were among the topics of a panel discussion at the end of May in New York City at the World Science Festival called “The Craving Brain: The Neuroscience of Uncontrollable Urges.” As the issue of addiction again gets attention, The Kavli Foundation invited three neuroscientists—including two panelists of the festival program—to discuss the bases of addiction, the challenge of developing new treatments in the face of the stigma many assign to addiction, and what sorts of research are most likely to lead to new effective pharmacological treatments. The participants:

- Nora Volkow is Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD.

- Eric Nestler is Nash Family Professor and Chair of Neuroscience and Director of the Friedman Brain Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

- Marina Picciotto is Charles B.G. Murphy Professor of Psychiatry and Professor in the Child Study Center, Professor of Neurobiology and of Pharmacology, and member of the Kavli Institute for Neuroscience, all at Yale University in New Haven, CT.

The following is an edited transcript of the discussion, which took place in a teleconference on May 15, 2014. The participants have also been provided the opportunity to amend or edit their remarks.

The Kavli Foundation: I would like to start out with the evolving definition of addiction. Nora Volkow, you chaired the working group of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), part of the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime. You observed in a blog post on NIDA's website that the members of the working group “...were in complete agreement that substance use disorders are a disease ... and thus should be addressed within a public health framework.” Were there any areas of disagreement within the group?

Nora Volkow: No, there were no discrepancies or disagreements. The CND's working group included scientists and clinicians from all over the world, and we had a whole day of deliberations in terms of what points the United Nations Office of Drug Control wanted to endorse in front of all of the delegates of the office. We came up with seven points resulting in a recommendation that addiction should be treated as a medical and public health issue rather than a criminal justice or moral issue and that the healthcare system should have the responsibility and capacity to deliver evidence based prevention and treatment interventions for substance use disorders. So it was recommended that countries allocate resources to strengthen healthcare system’s ability to address substance use disorders, or SUD.

The working group also discouraged criminalization of substance abusers. The committee also recommended that prevention is the most effective intervention to address SUD. A recommendation was also made that the UNODC should form a permanent scientific council to serve as advisors to the Commission on Narcotic Drugs.

The only issue where there was some difference of opinion was that we wanted to explicitly state that medication-assisted therapies were very valuable not just in the treatment of substance use disorders but also for prevention of infectious diseases like HIV, which substance abusers are particularly vulnerable to contracting. We couldn't do this because the Russian delegation does not support the use of methadone and/or buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid addiction.

TKF: How new is the idea that addiction is a disease?

Volkow: In 1997, Alan Leshner [then the Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or NIDA] published a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine that was titled "Addiction is a Disease of the Brain and It Matters." However, it's taken a very long time not just to accept the concept of addiction as a disease of the brain, but actually to endorse it and recognize that the healthcare system needs to be involved both in the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders.

There has been a large increase in the abuse of prescription medications, which in the United States is the main driver of deaths from overdoses. It's a problem that emerged from the healthcare system itself because physicians have started to overprescribe opioid analgesics. We are seeing addiction now emerging in patients with chronic pain who were given the opioids for a bona fide reason: they have pain. And they have taken the medication properly yet they are becoming addicted.

This is a very unfortunate set of circumstances. The only positive aspect to it is that it has forced the healthcare system to take a look at the process of addiction and how to prevent it and treat it.

TKF: Eric Nestler, when you began your work on addiction, which was a decade before Alan Leshner's seminal paper, were neurobiologists skeptical that addiction is a disease of the brain?

Eric Nestler: My first grant proposal to NIDA focused on looking at how repeated activation of the opioid receptor induced changes in the brain, and it was rejected. The reviews of the proposal commented that there is no evidence of such molecular changes being involved in the addiction process.

I think there remains significant pushback to the notion that addiction is a disease because, at some level, being an addict requires a person to make a decision to take a drug, and maybe an illegal drug. And for that reason, society confuses a volitional act—willfully taking a drug—with a disease process in the brain that is extremely strong and that is driving that maladaptive behavior.

Right, Nora? We know people who in the medical community as well as politicians who push back very strongly on the notion that addiction is a disease.

Volkow: We receive frequent criticism from those who say that by claiming drug addiction is a disease we are actually removing the responsibility of the person that is addicted for their behavior. This is a non sequitur. The fact that you have a disease does not remove your responsibility to take care of it.

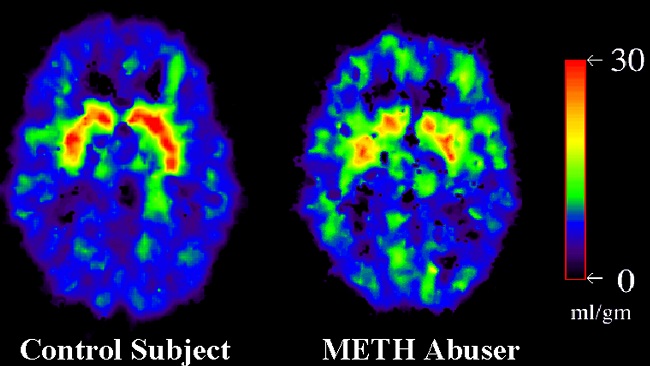

Nestler: The abnormalities that drugs of abuse produce in the brain attack free will, such that drugs of abuse are corrupting the very nature of a person's volitional choice. That is part of the disease.

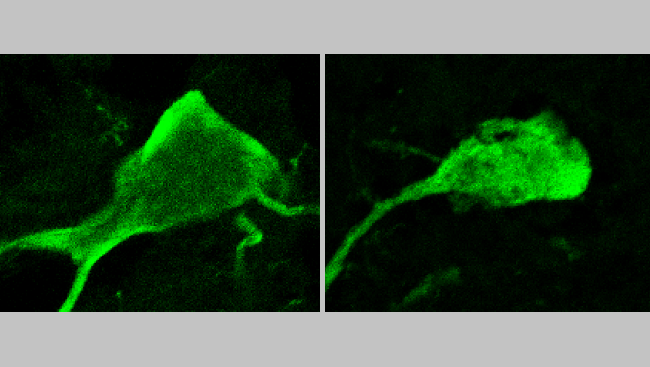

Marina Picciotto: That's exactly right. Drugs of abuse change the brain in a significant way such that decision making is permanently, or at least on a fairly long-term basis, impaired. And therefore free will as we know it is not gone, but it is so severely modulated that someone who is not addicted has a hard time understanding that loss of volitional control.

Because of genetic and environmental variations, some individuals do have an easier time quitting smoking or drinking alcohol than other individuals. The existence of this group seems to bolster an argument against addiction being understood as a disease: “Well, this person had an easy time quitting. And therefore if you can't do it, it's a weakness of character, it's a lack of free will.” In fact, it’s likely to be a profound difference in neurobiology across individuals that make it much, much more difficult for some people to stop taking both legal and illegal drugs than others.

Nestler: Absolutely. That's really well said, Marina. And just to further expand on this, for many non-brain diseases, there is still the involvement of free will. Consider people who have a myocardial infarction and need to lose weight and exercise more. A large subset of people with that illness don't follow through with changing their diet and exercise, yet society doesn't blame them.

TKF: That brings to mind the stigma surrounding obesity, which seems to be very similar to the stigma surrounding drug addiction, in that obese people are often stigmatized for not having the willpower to eat less and lose weight.

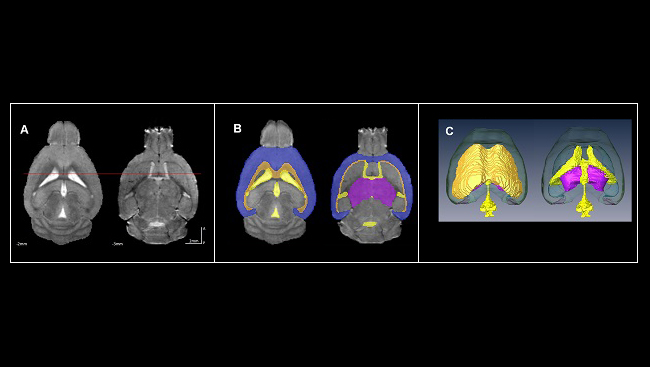

Volkow: Right, and I think that, in fact, we are learning in both directions. Findings that have emerged out of clinical and pre-clinical research in substance use disorders are now informing us about the loss of control in individuals who are compulsive overeaters. Likewise, information related to the mechanisms by which our body controls and regulates the drive to eat, such as peripheral mechanisms related to production of insulin or the appetite-regulating hormones ghrelin or leptin, are now informing us about the role in modulating the sensitivity of the reward systems in the brain, including the sensitivity to drugs of abuse. That overlap makes a lot of sense, because these circuits did not evolve for us to take drugs. These circuits evolved to ensure that we eat properly. What we are seeing in addiction are drugs literally hijacking systems that took millions of years of evolution. And that's why there is no surprise that we see so many similarities in the behavioral expression of compulsive overeating and loss of control and that associated with compulsive drug taking in addicted individuals.

This relates to a point that Eric and Marina made, which is that of intention and responsibility. What is intention and how does that relate to the concept of free will and self-determination? And what is intention as it relates to the public health system doing something about the problem? So, an addict might have the intention to go to a treatment program in order to get better. Believing that this action can be effective is at the core of arguments saying it is a necessary step for someone to be able to stop using drugs. And yet, as research is emerging, there is data to show that strengthening those frontal areas of the brain involved with executive function—our ability to manage multiple streams of information, which is ultimately necessary to exert self-control—through techniques such as meditation enables people to stop taking drugs even if they have no intention to do so. We all believe that it is our conscious intentions that determine what we will do or not do. And it's not necessarily so.

Picciotto: There is one case study that really backs that up, and that's again from smoking, which is my area of interest. When the antidepressant Wellbutrin was first prescribed to depressed subjects, primary care physicians reported that some of their patients who were on the drug came in and said, “Doc, the funniest thing happened, I just didn't feel like smoking anymore, so I stopped.” And that was how that particular antidepressant was developed as a smoking cessation treatment. Tobacco was a drug that could cause them serious physical harm and the biological reasons for taking that drug—which might include, say, depression—could be counteracted by a medication.

TKF: In some study protocols, researchers have presented addicted people with images of drugs or drug paraphernalia, and these images activate the reward areas of the brain just as they would if the person were to use the drug. Nora, what has science told us about the environmental drivers of drug use?

Volkow: That's another area for which the knowledge has exploded and there has been great in-depth understanding about what the mechanisms are by which these conditioning responses are produced in drug users. In general, conditioning is a type of memory that is crucial for survival, and obviously of extraordinary importance for us to, for example, learn what we should eat and not eat.

In an addicted person, what actually generates a desire to take the drug is not the action of taking the drug, but the conditioned responses surrounding almost every activity he or she does. For things like tobacco it can be constrained to environments where individuals take the drug to help them relax. We are very much interested in developing interventions that can reverse these conditioned responses, by tapping into the knowledge that we have about memory and learning so that we can develop strategies that can be used, for example, to weaken a memory [i.e., a conditioned response]. And alternatively, searching for interventions that we can do to strengthen a new memory that will beat out the other one that drives an addict to reach for a drug.

Picciotto: I think that one of the things that the brain does extremely well is to associate anything in the environment that is going on when individuals get a natural reward as something that they should, for evolutionary reasons, pursue. So, imagine that you're hungry and you find food. You really should be able to see all the things in the environment that are associated with that important food and go toward those cues whenever you need that food. The same is true with drugs of abuse. They are activating the parts of the brain that react to all other rewards as well, and everything that is going on in the environment. When that very potent drug activates those reward systems, it is going to be encoded as a very powerful memory. And we think those environmental cues, which are now profoundly associated with that drug, will now take over behavior. Drug users are actually going to approach those cues and then crave that drug when they are in an environment that has previously been paired with that drug. It's very primitive; it's evolutionarily favored for the brain to do this.

Nestler: Our brains evolved to remember where we found food, sex, potential predators and to teach us to return to where we got food and to stay away from places where there are predators.

TKF: With the exception of smoking, drug use and addiction are on the rise. There are a handful of pharmacological treatments for nicotine, alcohol and heroin addiction, and scientists are now developing vaccines to treat addictions. Nora, are you optimistic about the potential for vaccines against addiction?

Volkow: So far, clinical trials for vaccines against heroin, nicotine and cocaine have been unsuccessful because the vaccines are unable to induce sufficient titers of antibodies necessary to stop the responses of the drug. I am optimistic, though, because the technology for vaccine development has advanced enormously. Part of the problem can be attributed to the difficulties in getting pharmaceutical companies that might have tools to help improve the antigenic response to share their proprietary technology.

TKF: With respect to the decline in tobacco use in the U.S., in addition to the increased awareness of the dangers of smoking, Marina, where are we with pharmacological therapies for nicotine addiction?

Picciotto: The one area in which we have had quite good success for medications is in smoking cessation. We now have many different targets. One of them, of course, is the antidepressant I mentioned earlier, Wellbutrin. But for smoking cessation we have one of the real success stories of modern molecular biology, which progressed through animal models and neurobiology experiments all the way through a medication that is successful in humans. And that is a drug called varenicline. It was designed to target the specific receptor for nicotine in the brain that is known to begin the process of stimulating the dopamine system that leads to the various effects of nicotine on addictive processes. Varenicline is a medication that can help many more people to quit smoking than previous existing nicotine replacement therapies.

Volkow: That is a very good example of how we can use science to come up with a solution to address drug addiction. And yet despite this success, there's a tremendous reticence from the pharmaceutical industry to invest in this area of research. So we have this paradoxical situation in which we have identified a large number of potentially very interesting molecular targets for medication development and yet pharma is not investing. So, despite the great potential to reduce the burden of disease nationally and globally, the relative investments for medication development are really embarrassingly low. So yes, we do have some medicines for heroin, some for nicotine, some for alcohol, but when you compare it vis-à-vis to the number of medicines that we may have, for example, for HIV, it pales in comparison. It relates back to the stigma of addiction: It's not considered worthwhile to invest resources to treat something that is considered part of a lifestyle choice.

TKF: We are living during a time when people with diseases that were once considered life-threatening are managed with medications. Do you think we are moving toward a context in which addiction can be managed by the healthcare system the way it manages diabetes or other chronic diseases?

Volkow: In principle, we should be there. I think that we should use the same model for addiction as the one used for other chronic diseases, one that has both a medical component, which the healthcare system naturally addresses, but also a behavioral one, which is something that is being incorporated more and more as part of the healthcare system. At the same time, the level of investments for addiction medications is much more limited than for any of the metabolic syndrome-related diseases like diabetes. And so we do not have the same variety of medications as are available, for example, for diabetes.

Nestler: If you turn the clock back 50 or 60 years to a time before antidepressants were introduced, no one in the field would have expected such robust chemical treatments of depression. So even though some people are skeptical today about medicines for treating addiction, we should be be very optimistic that we will achieve the day when effective treatments will be available.

— Joe Bonner

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

The Kavli Foundation

Also In Addiction

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org