What Can Prairie Voles Teach Us About Empathy?

- Published9 Oct 2024

- Author Bella Isaacs-Thomas

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Interpersonal connection is crucial to building relationships. Humans aren’t the only ones – other species form close bonds, too. Animal studies can reveal the neurobiological roots of why social creatures – including people – behave the way they do.

Researchers investigating empathy in prairie voles, which form monogamous pair bonds and physically console their distressed mates, examined parts of the brain involved in this behavior. Neuroscience PhD candidate Sarah Blumenthal presented the team’s preliminary findings at Neuroscience 2024, the Society for Neuroscience’s annual meeting, in Chicago.

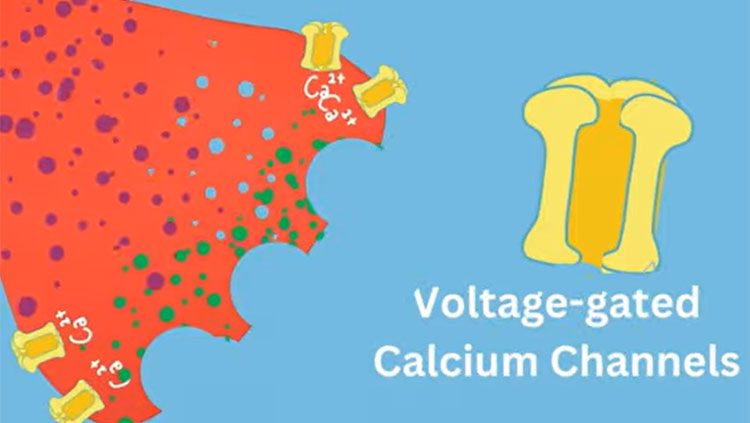

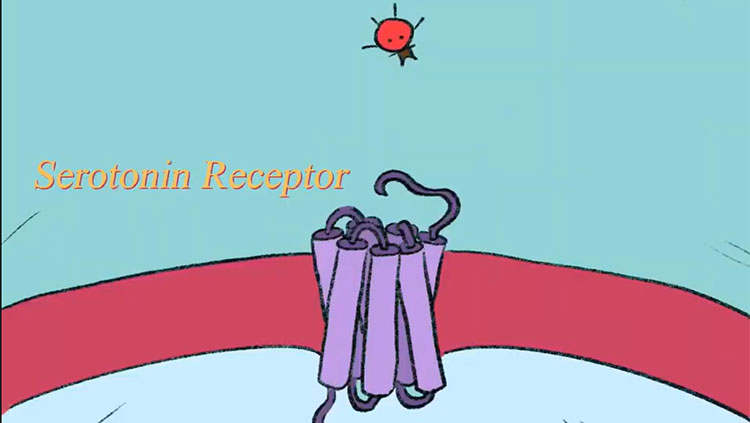

Previous research demonstrated the brain’s anterior cingulate cortex, or ACC, is activated when humans experience empathy or when prairie voles see their partner in distress. The Emory team tinkered with receptors for the neuropeptide hormone oxytocin in the ACC in prairie voles to assess its role in their consolation response.

Oxytocin is linked to a range of social behaviors in several species, including enhancing empathy among humans. “[Oxytocin] receptors are located on cells that are communicating with many different regions and are influenced by other neurotransmitter systems,” Blumenthal noted. “So, I really wanted to understand: What’s the role of the receptor, versus the cell that the receptor is located on, within the ACC?”

Blumenthal prevented the ACC from communicating in response to oxytocin in two ways. First, she deleted oxytocin receptors in the vole’s ACC. Second, she used a drug to inhibit ACC cells from communicating with other cells.

By comparing the behavior of altered voles to the behavior of control voles, the researchers discovered when reunited with a partner that was shocked into a state of distress, the control voles vigorously groomed their partner in a demonstration of their consolation behavior.

However, voles lacking the oxytocin receptors or those with inhibited cells in their ACC, didn’t offer their shocked partners any extra grooming. This behavioral shift indicates oxytocin signaling in that region is key to prairie voles’ ability to console their partners, Blumenthal said.

Humans and prairie voles have very different brains. But rodent models play a major role in neuroscience research because the two have plenty of useful parallels, said Morgan Gustison, a neuroethologist at Western University in London, Ontario, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Those analogs have important human health implications because they shed light on how our brains work and, potentially, how to use our underlying neurobiology to help people.

Around 20% of adults in the United States live with mental illness. A range of psychiatric conditions – including autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia – can involve empathy deficits which make it harder for those who live with them to maintain relationships with other people, Blumenthal noted. She said research like hers could one day inform targets for therapeutic interventions designed to help patients who want them to help improve their ability to engage socially.

“We need to continue to study empathy and the mechanisms in our brain that drive us to have empathy to better understand how we can treat these deficits,” Blumenthal said.

Animal models offer a unique opportunity to tweak and monitor the brain with tools that can’t safely be used on humans. Blumenthal deployed a virus-based technology which allowed prairie voles to move around freely, unhindered by clunky external research tools, Gustison said. “It's nice because you can really let the voles do their thing and be able to not have much extra stuff there that could affect how they're doing the social behaviors.”

In her lab, Gustison and her colleagues also study prairie voles. They focus on the role communication plays in facilitating pair-bonded relationships over time. Previous research has indicated that oxytocin is key to pair bonding among this species, but Blumenthal’s research has offered novel insight into the role these cell types in the ACC play with regard to their consolation behavior, Gustison said.

“I think everything about [the study is] pretty fun,” Gustison said, adding that it “opens the door” for future inquiry into other parts of the brain involved in the social behaviors of this unique species.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

What to Read Next

Also In Genes & Molecules

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org

.jpg)