Some Ground-Dwelling Dinos Had the Brains to Fly

- Published12 Mar 2015

- Reviewed12 Mar 2015

- Source Science Friday

Researchers discover that even non-flying dinosaurs had brains with the motor and visual capabilities necessary to take wing.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

Science Friday

Transcript

Next up, dinosaur brains. You've never seen a fossilized dino brain in the museum, right, you just see the bones. Brains, soft tissue, they don't last long. But my next guest has figured out a way to reconstruct the brains of dinosaurs using just the shape of their skulls and has made a startling discovery. This week, she and her colleagues published a paper in the journal Nature saying that even dinos, who spent most of their time on the ground, may have had the brains to fly.

In other words, there may have been some sort of earlier bird brains around. Amy Balanoff is a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History here in New York. She's here in our New York Studios. Welcome to SCIENCE FRIDAY.

AMY BALANOFF: Hi, thank you.

FLATOW: How did you actually reconstruct the brain?

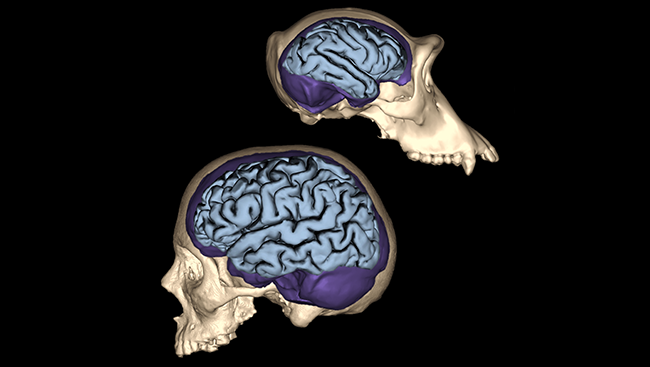

BALANOFF: Well, that's a good question because like you said, brains are not something that gets fossilized. So - and most soft tissue structures don't fossilize. And so what we did is we used CT scanning to reconstruct the brains of these extinct animals. So CT scanning, the way we did it was just like a medical CT scanner, but what we used was one that has much higher energy X-rays so they can penetrate things like fossils that are fairly dense.

And then that just slices the skull up into nice, neat little slices, and what's really interesting about things like birds and mammals that fill most of their cranial cavity with their brain, it's very lucky for us that they do fill up most of that cranial cavity because as the brain develops, it leaves an impression on the bones surrounding the brain.

So if you can somehow make a cast of that space where the brain sat during life and get rid of the bones, then you'll have a cast of what the brain looked like during life. And what we do is use the CT scans to get at that space and make a digital cast of the space.

FLATOW: But once you know what the brain looks like, how can you tell what function that part of the brain had?

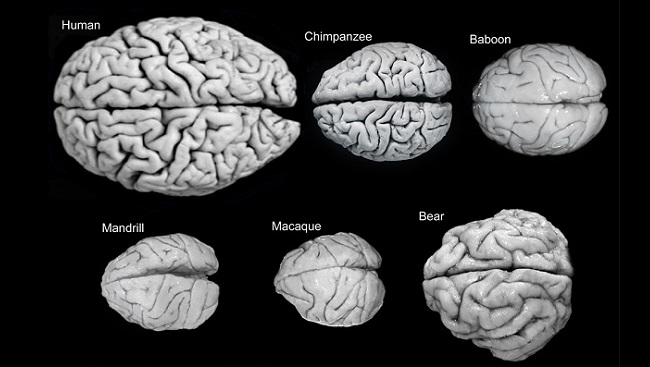

BALANOFF: Well, we can use things like the size of the different regions. So if something has fairly large, or very large, olfactory bulbs - this is the region of the brain that controls the sense of smell - if they have large olfactory bulbs they had a good sense of smell. If they have large visual centers then they could probably see pretty well. Or maybe they might've been nocturnal, something along those lines.

FLATOW: Mm-hmm. And so what did you discover? What was the amazing discovery you made about these brains?

BALANOFF: Well, what was really interesting was that - we looked at animals that were very closely related to Archaeopteryx. And Archaeopteryx is this fossil that's always been - historically has always been kind of held up as the transition species between dinosaurs and living birds. But what we found is that when we looked at Archaeopteryx and we looked at dinosaurs that were very closely related to Archaeopteryx, that they had brains that were at least as large as the Archaeopteryx brains and in some cases even larger.

So Archaeopteryx certainly had the capacity to fly at some level. And so if Archaeopteryx could fly, then by inference these other things had the neurological capacity to fly, not necessarily that they were also taking to the skies. But that brain was already there.

FLATOW: So instead of a chicken and egg, you have a brain or a bird.

BALANOFF: Yeah, exactly.

(LAUGHTER)

FLATOW: First. Right? So it knew it could fly but it didn't have the wings or the feathers yet or the knowledge?

BALANOFF: Well...

FLATOW: And it knew it had the wiring, are you saying?

BALANOFF: That those dinosaurs that we know are most likely cursorial, or they were walking or running on the ground, yeah, they had that capacity, that neurological capacity to fly. Again, not necessarily that they were taking to the skies or anything like that.

FLATOW: Mm-hmm. That even makes it, you know, closer the idea that birds and dinosaurs were the same.

BALANOFF: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. This was actually - that's borne out by other studies, you know, people looking at the evolutionary history of dinosaurs. There are so many characters that they share, that birds and what the non-avian dinosaurs share in common that it's not really hotly debated anymore.

FLATOW: Yeah. You must have - you know, you watch birds do weird things when they fly. They can hover. You know, they can do all kinds of precise motions.

BALANOFF: Right. Exactly. And so that's - that is one of the things that, you know, requires a lot of brain power, I guess is the best word for it. Is that they have very fine control over their feathers and they can maneuver in three dimensions. And so there are all sorts of things that brains - that dinosaurs do during flying that requires a lot of brain power.

FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Do we have that? Do we have enough brain power to fly if we strapped a wing on us?

BALANOFF: Humans probably would. And I think that we've actually proven that by building airplanes.

(LAUGHTER)

FLATOW: So where would you go with your research now? What do you not know or how would you move forward on this?

BALANOFF: Right. That's a good question. Well, there are a few things. What we were looking at specifically was the volume of the brain, the volume of the brain compared to the body size of the animal. But what we'd like to do next now is to look at the shape of the brain, see how the morphology of these different regions are changing along the evolutionary history of birds.

FLATOW: Mm-hmm. I'm Ira Flatow. This is SCIENCE FRIDAY from NPR talking with Amy Balanoff from the American Museum of Natural History. Can you use, then, this brain size and the ability perhaps to fly as a guidepost to the evolution of dinosaurs and evolving, from birds, dinosaurs? Is it helpful at all?

BALANOFF: It is helpful. But what I think is really interesting about this is that so many of these characters that we thought made up a bird are now just - keep falling down the evolutionary tree of dinosaurs. So, you know, we always thought birds were these things that flew, that had big brains, they had a wishbone, they had feathers, and all of these things you find so much earlier in the history of - well, within the non-avian dinosaur lineage that it's becoming harder and harder to say exactly what a bird is.

FLATOW: Yeah. Because if you go back and then you look at the brain cast of other dinosaurs, you see they had it also.

BALANOFF: Yeah. Exactly.

FLATOW: So the birds that can actually fly or had wings and feathers might be a minority of the birds?

BALANOFF: Well, you could - the birds are so diverse that...

FLATOW: Yeah.

BALANOFF: ...it's hard to say they're a minority, but, yeah. They're not as unique as we thought they once were.

FLATOW: If you had a chicken today - and I remember once we talked about this years ago when people started talking about it. It was either Neil Degrasse Tyson or somebody else came on, or Mark Norell, these people came on from your museum. They said, you know, if you take a chicken bone and you go to the Museum of Natural History and you hold it up to the dinosaurs, you'll see the same bone on the dinosaurs.

If you - can you do that with a chicken head? Can you look at - hold the chicken's head up, say look at the brain case, it looks just like a dinosaur?

BALANOFF: You know, it's not far off. They share so many, many characters in common. They share a lot of features in common. So, yeah. Yeah. It doesn't - it may not look exactly like a chicken but it's close. It's very close. I mean, and there's a reason that these things are - they're closely related.

FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Can you tell anything about - else about dinosaurs from these models you made? Were they social creatures? Did they have any other abilities that you can discover from the brain?

BALANOFF: It's a little hard to go into too much detail. I mean, we don't have the internal structure of the brain. So we're missing some of the key components to figure out things like that. Like I said, what we can do by going - we're looking at the surface anatomy of the brain. So we can see sizes of different regions of the brain.

And one of the things that these birds or that these non-avian dinosaurs share in common with living birds is that they both have very large forebrains. That's like the cerebral hemispheres. It's the part of the brain. And so both of these groups are - this group, they all have a very large forebrain. And this is where, like, cognitive centers are, so.

FLATOW: Mm-hmm.

BALANOFF: But, you know, it does kind of speak to, like, social behavior and things like that, but it's hard to say for sure. You don't want to stretch things too far.

FLATOW: You know, we've talked about this for so many years we think what else can you learn, but there's always something new it looks like.

BALANOFF: There's always something new. Yeah. And we need a - I mean, another thing that we want to do is to add more species too.

FLATOW: Yeah.

BALANOFF: We're still not done with the - there's a big space between Archaeopteryx and living birds and that needs to be filled in. And that's one of our future areas of research.

FLATOW: Yeah. We'll have you back to talk about that when you can fill those features in. Thank you, Dr. Balanoff. Amy Balanoff is a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History here in New York. After a break we're going to do - our dino doubles can continue with a look at the cousin of triceratops with the big nose. So stay with us. We'll be right back after this break.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

FLATOW: I'm Ira Flatow. This is SCIENCE FRIDAY from NPR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Copyright © 2013 NPR. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to NPR. This transcript is provided for personal, noncommercial use only, pursuant to our Terms of Use. Any other use requires NPR's prior permission. Visit our permissions page for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by a contractor for NPR, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of NPR's programming is the audio.

Also In Evolution

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org