Realizing the Benefits of Vagus Nerve Stimulation

- Published24 Apr 2019

- Author Siddhi Camila Lama

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Kelly Owens remembers the first time she felt sick. As a 13-year-old who loved everything from basketball and field hockey to theater, she was a bundle of energy. So, when she twisted her ankle during a community theatre rehearsal for “The Music Man,” she was devastated as it swelled up.

Despite assurances that it was nothing more than a minor injury, it never got better. Eventually, her doctor removed 10 milliliters of fluid from her ankle only to have it return the very same evening. A few weeks later, she started experiencing gastrointestinal distress so severe she was forced to leave class every few minutes to go to the bathroom.

“I felt confused,” Kelly said. “To go from being an active, athletic kid, to all of a sudden having my body seem to be at war with me at that young of an age, felt strange. Everything suddenly felt foreign and out of my control.”

The diagnosis came pretty quickly: Crohn’s disease — an inflammation of the gastrointestinal track — with manifestations of inflammatory arthritis.

Kelly struggled for the next 16 years to manage symptoms and combat Crohn’s. The arthritis spread to every other joint in her body, all the way up to her jaw. She suffered from colitis and other Crohn’s symptoms, like ulcers on her legs. She tried every conceivable drug available to squelch her symptoms and relieve the inflammation.

“I’ve been on every biologic, DMARD, and immunosuppressant under the sun available for Crohn’s disease,” said Kelly. “None of them worked for too long, if at all,” she said. “My body always built up antibodies against everything, and on top of that, all of these medications made me feel like a nuclear power plant. For 16 years, the only thing that ever held me over were steroids.”

But long-term steroids have side effects too. By 25, Kelly was diagnosed with osteoporosis caused by the chronic use of this medication, as well as malabsorption due to the colitis.

That same year, Owens was living in Hawaii and teaching English. “I’d come home from work, prop my knees up on pillows, and ice my legs while grading and lesson planning. Then, I’d do it all over again the next day... until I couldn’t anymore,” she said.

While browsing the Huffington Post, she found an interview of Kevin J. Tracey, a neurosurgeon and the CEO of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, discussing bioelectronic medicine. His research showed how the small zaps of electricity to the vagus nerve could stop the over-production of inflammatory cytokines. “As I watched him explain this in the interview,” Kelly said, “I knew this device would eventually change my life. I tracked down his email and told him my story.” At that point in time, in 2014, Tracey’s vagus stimulation research was being tried on rheumatoid arthritis patients. Meanwhile, Kelly’s symptoms worsened so much that she had to stop teaching.

It wasn’t until early 2017, when her doctors informed her there were no more medications left to try that Kelly contacted Tracey again. SetPoint Medical had just started a clinical trial using vagus nerve stimulation for Crohn’s disease.

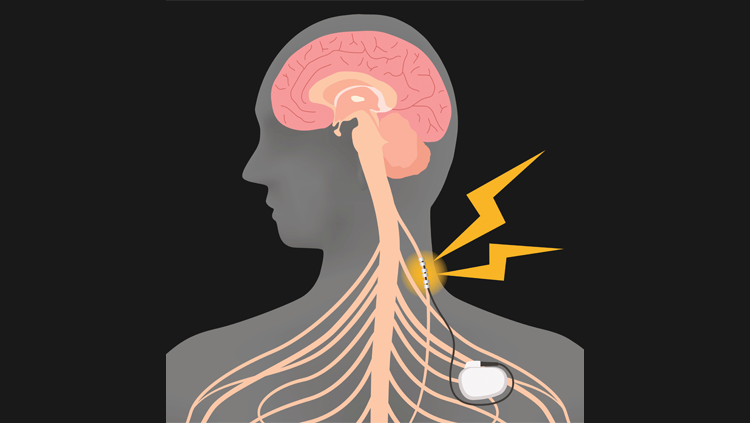

By July, Owens underwent an experimental procedure implanting a battery-sized device into her chest to deliver small amounts of electrical stimulation to her vagus nerve. The result has been life changing.

“I just don’t have symptoms anymore,” Kelly says. “It’s not like symptoms creep back up at night or in the morning or any time in-between — and my body is at peace. For a woman that couldn’t walk for more than a few minutes without needing to rest and sometimes needed a wheelchair, I now find myself going on hikes that can last for miles, running on the treadmill, and rediscovering what my body is capable of.”

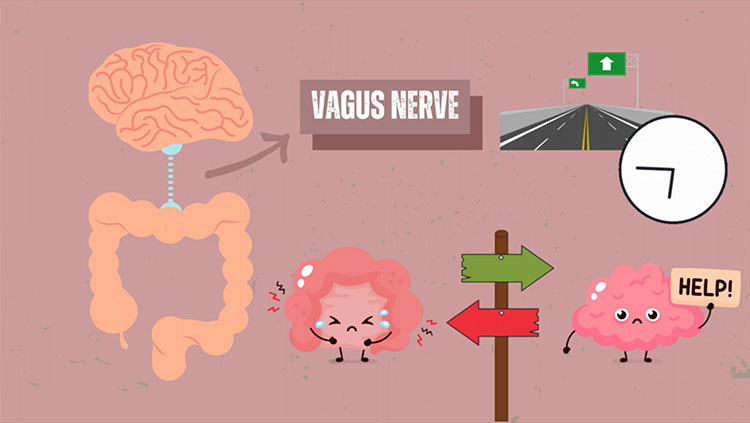

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) worked for Owens because it dampened the inflammatory markers causing her Crohn’s disease and arthritis. For Owens, VNS targets her spleen to reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. But VNS isn’t only used to treat inflammatory conditions, in part because the vagus nerve impacts so many parts of the body. As the body’s longest cranial nerve, the vagus nerve has sensory and motor fibers running from the brainstem through various organs, including the heart, lungs, stomach, and intestines, ending in the colon.

Over the last 30 years, VNS has been used to treat various diseases, including treatment-resistant depression, treatment-resistant epilepsy, chronic migraines, and cluster headaches. VNS devices are typically implanted, like Kelly’s, but recently, non-invasive versions of VNS, which can be applied through your ear, are also being explored.

Dr. Matthew Leonard, Assistant Professor of Neurological Surgery in the Weill Institute for Neurosciences at the University of California, San Francisco, has been exploring non-invasive VNS’s use in language learning. In one of Leonard’s recent studies, non-invasive VNS was able to enhance people’s ability to learn a well-known linguistic challenge: Mandarin tones.

However, it’s still unclear how similar non-invasive VNS is to an implanted VNS device, which is why Leonard’s team is currently trying to compare the two. “We record neural activity directly from the human brain in patients with epilepsy, some of whom also already have implanted cervical VNS devices, and who volunteer to wear our ear device for a few minutes,” said Leonard. This allows these researchers to see if the stimulation in the brain is similar between these invasive and non-invasive approaches.

It’s not even just about the type of device — there are other factors, like the strength of the stimulation, how it’s applied, and even the electrode materials that can play a role in VNS. According to Leonard, “the field is in an exploratory phase right now, as we investigate approaches that can engage this deceptively simple nerve in a wide array of applications.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Nesbitt, A. D., Marin, J. C. A., Tompkins, E., Ruttledge, M. H., & Goadsby, P. J. (2015). Initial use of a novel noninvasive vagus nerve stimulator for cluster headache treatment. Neurology, 84(12), 1249. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001394

Ogbonnaya, S., & Kaliaperumal, C. (2013). Vagal nerve stimulator: Evolving trends. Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine, 4(1), 8–13. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.107254

Penry, J. K., & Dean, J. C. (1990). Prevention of Intractable Partial Seizures by Intermittent Vagal Stimulation in Humans: Preliminary Results. Epilepsia, 31(s2), S40–S43. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1990.tb05848.x

What to Read Next

Also In Body Systems

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org