A Gut Feeling: Our Microbiome and the Brain

- Published21 Sep 2017

- Reviewed21 Sep 2017

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Recent research has revealed a potential connection between the brain and the trillions of microorganisms colonizing the body.

This video was produced for the 2017 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

My gut tells me something is up. Oh, but does a ‘gut instinct’ really exist, or is it merely a figure of speech? The idea that our gut exercises influence over our state of mind isn’t new - according to Scientific American, many 19th and 20th century scientists believed that some cases of depression, anxiety, psychosis, and the like were linked to waste accumulating in the colon. Colon purges and sometimes bowel surgeries weren’t all that uncommon before they were discarded as unscientific. These scientists may have been on to something - you likely won’t be surprised that there exists a series of biochemical signals between our gut and the brain, called the brain-gut axis. What may be surprising, however, is the fact that many of these signals are being transmitted and received by tiny organisms called microbes, tucked away in your innards, collectively forming what is called your microbiome.

That’s right! Believe or not, at this very moment, your thoughts are partly being mediated by these miniscule visitors residing in your gastrointestinal tract! Find that hard to believe? Let’s look at the experiments! Microbes seem to have an astounding effect of the social aspect of our personalities. According to Scientific American, a group at McMaster’s University found that when they took microbes from one mouse and introduced the sample to another, the latter often exhibited personality characteristics similar to those of the original microbe owner! Shy mice would become slightly more bold, while ordinarily audacious mice would become more cautious and shy.

Yet another group at Caltech noticed that women who suffered from prolonged fevers during pregnancy were more likely to give birth to autistic offspring. They introduced a viral mimic that led to fevers in pregnant mice. The offspring exhibited antisocial and repetitive behavior, two key symptoms of autism in humans.

Subsequently, it was found by another group that the same mice offspring had higher levels of two certain bacteria strains, suggesting a link between the microbiome and autism. The microbiome may reach roots as deep as gene expression - one study at the APC Microbiome Institute found that germ-free mice, which have near to no gut bacteria, have altered gene expression in the amygdala, a part of the brain heavily involved with fear and social behavior.

Certain genes related to neuronal function seemed to be more active than those in normal mice. How and why does this work? The answer is very complex, and science cannot yet offer a complete answer, but plenty of progress has been made that we can talk about in the next couple of minutes. First off, why might microbes cause us to be more social? One possibility is that, in order for the microbes to spread throughout the human population, it is evolutionarily advantageous for them for us to come in contact with as many other people as possible.

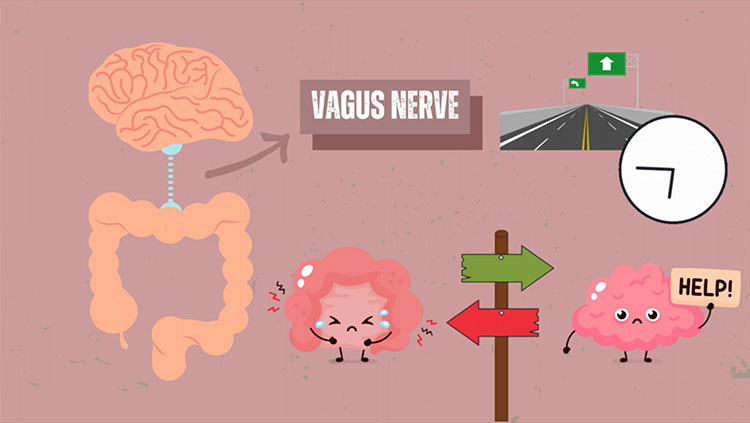

How then, do the microbes communicate with our brain? There are multiple pathways. The first pathway involves the vagus system, a series of nerves that sends automatic signals between our gut, heart, lungs and the brain. The vagus nerve is bidirectional, meaning that the gut can send signals to the brain and vice versa. The immune system is heavily involved as well - it monitors our gut composition, ensuring that no pathogenic foreign microbes enter our bodies. The intestinal microbiome can prompt the immune system to secrete more cytokines, cell signaling molecules that can subsequently affect brain function. Microbes themselves can also directly secrete molecules that affect brain function. Certain metabolites from gut microbes promote serotonin production in the cells lining the colon.

Another class of metabolites, called short-chain fatty acids (or SCFAs), are neuroactive bacterial metabolites that can also affect behavior. One well-known example of this is butyrate. Now that we’ve determined that our microbiome may have an effect on our brain, one implication for the future is the development of psychobiotics, probiotics that intervene with mental illnesses (such as anxiety and depression) by introducing new gut bacteria.

However, most research that has been done with psychobiotics has been done on mice, and not humans. It has yet to be determined whether or not manipulating your gut make-up can significantly alter your mind and mood. An alternative are natural probiotics, which include fermented foods, such as yogurt and kimchi, that can introduce healthy bacteria into your gut. What do you think - will psychobiotics be the new antidepressants of the future?

Also In Body Systems

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org