Animal Research Success: Parkinson's Disease

- Published9 Mar 2012

- Reviewed9 Mar 2012

- Author Emily K. Dilger, PhD

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Parkinson’s disease is a chronic, progressive disease that typically begins around the age of 50 and is characterized by muscle tremors, stiffness, slow movements, and poor balance. Animal research has a long history of advancing understanding of Parkinson's disease. Two major treatments currently being used are a result of this work, and they have greatly improved the quality of life of people with this disease.

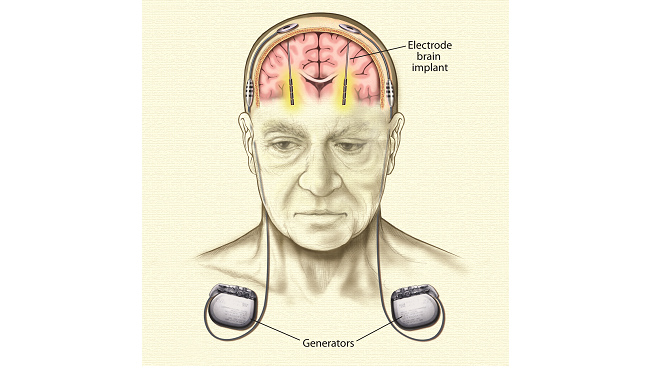

Thousands with Parkinson’s disease have been treated with deep brain stimulation. One or two small generators inserted under the skin, usually near the collar bone, emit tiny electrical pulses that pass along wires, also under the skin, to electrodes implanted in select areas of the brain. Deep brain stimulation works by blocking the abnormal nerve signals that cause tremor and other symptoms of Parkinson’s.

James Parkinson was the first clinician to describe Parkinson's disease in the early 1800s, but no significant medical advances were made until the 1950s. Using rabbits and mice, Nobel Prize winner Arvid Carlsson, MD, PhD, realized that a neurotransmitter called dopamine was affected in people with Parkinson's. Carlsson and his team then discovered that the drug reserpine, which caused symptoms similar to Parkinson's in the animals, depleted the animal’s dopamine. Other scientists looking at the distribution of dopamine in the brains of pigeons found that it was highly concentrated in the basal ganglia, an area of the brain involved in motor function. This finding led to the realization that in people with Parkinson’s, cells in the basal ganglia die, causing the production of dopamine to be reduced.

Putting all these pieces together, it became clear that to treat Parkinson's disease scientists needed to find a way to increase dopamine levels in the brain. In 1970, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved such a medication – a drug called levodopa, which is converted to dopamine in brain cells.

Once scientists understood the role of cell death in the basal ganglia in Parkinson's, they were able to replicate the disease in monkeys. After giving monkeys drugs that cause cells in the basal ganglia to die, scientists found that other regions of the brain – the subthalamic nucleus and globus pallidus – became overactive in response to lowered signals from dopamine. Scientists realized that by stimulating these areas of the brain they could quiet the overactivity and relieve symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Deep brain stimulation involves the implantation of a brain pacemaker, which sends electrical impulses to specific parts of the brain. This procedure was approved for Parkinson's disease in 2002. It has the benefit of being reversible and adjustable to the needs of the patient.

Levodopa remains the most effective form of oral treatment today, and deep brain stimulation is a good option for those who have adverse reactions to levodopa. However, neither of these treatments addresses the progressive nature of the disease. While there is no cure for Parkinson's, ongoing research using animal models is helping scientists come closer to realizing this goal.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org