The Brain on Trial

- Published1 Dec 2011

- Reviewed1 Dec 2011

- Source The Kavli Foundation

Society for Neuroscience

Increasingly what we know about the brain is affecting what happens in the courts. Recently, the U.S. Supreme Court decided adolescents could not be eligible for the death penalty partially based on neuroscience evidence that indicated the teen brain is not fully mature.

Defense attorneys have also used brain scans to suggest their clients' actions were influenced by brain damage or abnormalities, as part of an argument for modified sentences. And the recent view of drug addiction as a brain disorder has raised questions about how drug addicts should be held accountable for their criminal behavior.

The rising influence of neuroscience in the courtroom was the focus of a Kavli Foundation teleconference that included Alan Leshner, Chief Executive Officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and former head of the National Institute of Drug Abuse, cognitive neuroscientist and neuroethics expert Martha Farah, director of the Center for Neuroscience and Society, University of Pennsylvania, and neuropsychiatrist Jay Giedd, MD, an expert in adolescent brain development at the National Institute of Mental Health and chief of NIMH's Unit on Brain Imaging in the Child Psychiatry Branch.

Together, these experts discussed what role neuroscience should have in determining legal policies and judgments, innovative brain-based treatments for certain pathological behavior, and how we are easily fooled by colorful brain scans. They also shared opinions on whether “painting a picture of the neural processes that give rise to criminal behavior” as Dr. Farah put it, can excuse that behavior or mandate lighter sentencing. Below is the edited transcript of that discussion.

-------------

THE KAVLI FOUNDATION: Dr. Leshner, to begin, in the context of neuroscience and the law, what does your field reveal about personal responsibility that you feel is not well understood?

ALAN LESHNER: There’s been a lot of controversy around the increased understanding that addiction is a brain disease and the implications of that for personal responsibility or law. The fact that you have a brain disease means that biologically, change in your brain has led to compulsive repeated drug use. But it doesn’t mean that you have no responsibility for any of your behavior. Are you less responsible? In a way you are, and that should be taken into account in sentencing; but more to the point, it means we should require treatment for drug addicts that commit an act against society while we have them under criminal justice control, because that would decrease significantly the probability they would commit crimes again.

TKF: Dr. Giedd, as an expert in adolescent brain development, do you think neuroscience insights can determine whether a person is legally responsible for his or her actions?

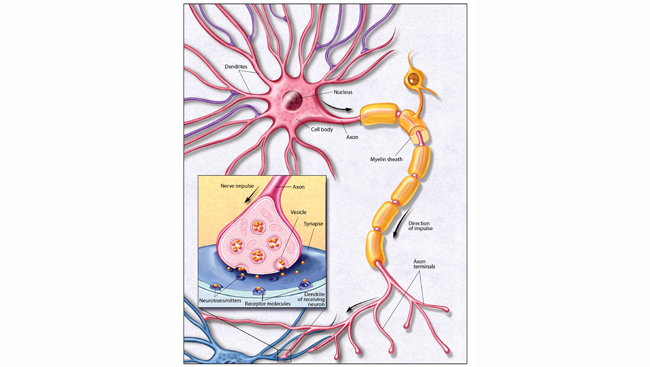

JAY GIEDD: What the neuroscientist is often asked is, “Was it the person, or was it his or her brain, that made them commit a crime?” To me this is a false dichotomy because the person and the brain are inseparable—everything we think, feel or do is a product of our brain activity. So even if we can trace the person’s actions back to the brain, that doesn’t change the personal responsibility for the crime, except for some rare but remarkable exceptions where someone might have brain damage or a brain tumor that dramatically affects their capacity to make decisions.

TKF: What about the sentencing of a convicted criminal. Does neuroscience have a role in determining or tempering the legal consequences of a crime, particularly among teenagers?

JAY GIEDD: On average, the 15-year-old brain is different than the 25-year-old brain. What’s difficult is applying this to individuals, is there are so many exceptions to the rule – there are many mature teens, and likewise immature people in their twenties and thirties. So the real challenge is going from group averages to individual prediction or characterization. One pretty strong group phenomenon is that teenagers don’t really think about the future the same way that older people do, so long-term consequences are less of a deterrent to their behavior. The other strong adolescent phenomenon is heightened sensitivity to peer pressure. The judicial system could focus on both of these adolescent phenomena when determining deterrents and interventions for adolescent criminal behavior.

TKF: Dr. Farah, what are your thoughts on this topic?

MARTHA FARAH: I agree with Jay and Alan. The mere fact that brain processes give rise to the behavior isn’t enough to excuse it and doesn’t diminish your responsibility for it in the eyes of the law.

TKF: So is it ever a valid defense to simply say, “My brain made me do it”?

JAY GIEDD: In 1966, Charles Whitman, the Texas tower shooter, killed 16 people and wounded 32 others. Brain scans revealed he had a brain tumor, which may have led to these aggressive, uncontrolled actions. But such cases are rare in which there is blatant damage to the brain that is obviously linked to the behavior that occurred. More difficult to discern are subtle brain differences that may not necessarily be linked to behavior. In these cases, colorful brain scans introduced in courts can be almost irrationally persuasive.

TKF: A picture says a thousand words.

JAY GIEDD: Yes, but not necessarily true words. There are several reasons why brain scans are often misinterpreted and can’t be counted on. One is that you’d have to be scanning the person at the time of the crime to accurately capture what their brain was like then, because brain states change second-by-second. Another reason is that there’s always the danger of making inappropriate inferences. People will look at a brain scan and say “Aha, there’s a bright color indicating heightened activity in this area of the brain that is involved in impulsivity,” even though there are thousands of other activities besides impulsivity that would also cause that same bright color in that spot of the brain. People notoriously overestimate our ability to go from the pictures to predicting behavior.

TKF: What has been your experience in how neuroimaging plays out in the courtroom?

JAY GIEDD: Attorneys present me with case histories of incredibly impulsive behavior—of young children hopping into police cars and driving them off without thinking about the consequences--and ask me to do brain scans to see if these kids are impulsive. But everything they’ve just said clearly demonstrates that these kids are very impulsive, so what their brain scans show doesn’t matter. We can use imaging to tell if someone can do long division just by showing them a problem while they’re in the scanner for about $600, or we can get the same information for three cents just by pulling out a pencil and paper and asking them what’s the answer to a long division problem.

TKF: What role do you think science should have in helping society or the courtroom determine when and how much someone should be held responsible for his or her actions?

ALAN LESHNER: Policy, including criminal justice policy, is always made on the basis of both scientific facts and societal values. But I would want to be assured that the science has been fully considered, and that we’re not denying, diluting or distorting it in the process of making public policy, including criminal justice policy.

TKF: You’re saying that science can provide the facts, but society still has to put a value judgment on top of it?

ALAN LESHNER: Absolutely. It doesn’t have to, it will. You need to recognize that that’s a part of the way the world works.

JAY GIEDD: There are several ways neuroscience can help shape judicial or other social policies, including influencing determinations of appropriate punishments for adolescent crimes or legal age minimums for certain behaviors or political offices. Neuroscience findings on adolescents, for example, led to many states adopting graduated driving licenses, which have saved a lot of lives. So neuroscience can be helpful in creating policies related to keeping teens safe and healthy, more so than determining punishment and retribution after they’ve done crimes.

TKF: It sounds like you’re more comfortable making scientific judgments about adolescents as a group as opposed to determining from an individual adolescent’s brain scan whether he or she is prone to abnormal behavior.

JAY GIEDD: Exactly, and that’s really been our greatest challenge, not just for the judicial system, but clinically as well. We can say the average schizophrenic brain is different than that of the average person without schizophrenia, but we can’t yet put an individual in a scan and tell if they have schizophrenia, or depression, ADHD, autism, etc.

MARTHA FARAH: Some of the most interesting implications of the neuroscience findings are for how criminals should be punished, as opposed to the question of how responsible they should be for their behavior. A lot of good could come from getting society more strongly behind the idea of therapeutic justice--sending someone to anger management therapy or parenting classes, for example. If people’s brains are causing them to do bad things and if we can fix their brains or foster healthier development of their brains, we’ll all be safer. The individual offender is better off and society is better off. So, by putting crime within that public health framework, it makes the idea of therapeutic justice more appealing.

TKF: So along with being punished, someone’s sentence might include drug therapy to alter how they think and behave?

MARTHA FARAH: We already sentence sex offenders to anti-androgen therapy—chemical castration. And that treatment works on the brain in addition to other parts of the body. It is a central nervous system intervention that’s supposed to help curb their antisocial urges and keep people safer. We may have more such therapies available as neuroscience goes forward.

TKF: So in the future, people might be incarcerated less and instead treated for behavioral offenses.

MARTHA FARAH: Yes, although it does raise the specter of Brave New World and state control of brain processes. The science can tell us what we can do, but society’s values will tell us whether we should do it.

ALAN LESHNER: But you’re not totally controlling the individual with that treatment—they go through treatment programs that don’t do away with their free will. So, both from a societal standpoint and an individual standpoint, they’re better off getting that treatment.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

The Kavli Foundation