Fear and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Published12 Oct 2009

- Reviewed20 Aug 2013

- Author Debra Speert, PhD

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Basic scientific research on the biological basis of fear is unlocking the mystery of post-traumatic stress disorder and suggesting new treatments.

In a given year, about 3.5 percent of Americans suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a punishing disorder marked by intense fear, anxiety, and flashbacks that follow a traumatic experience. For U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, the prevalence of PTSD may be as high as one in five. Until now, there have been few treatment options to combat PTSD. However, new basic science and clinical research on the biological basis of fear suggests promising new therapeutic avenues.

Pavlov's dogs and the psychology of fear memory

Fear is an innate, universal emotion. It helps animals, including humans, avoid or escape dangerous situations. But, for those who experience painful trauma, fear can become chronic and debilitating.

Pavlov's dogs

Surprisingly, what researchers know about the psychology of fear has its basis in studies of the stomach. Ivan Pavlov received the Nobel Prize for research on digestion, but along the way, he accidentally revolutionized what was known about the brain and behavior.

Pavlov studied chemicals in saliva. He was surprised to find that not only did the dogs in his study salivate when presented with a meal, but they also drooled when they saw anyone in a lab coat. Surmising that the dogs learned to associate the lab coats with the technicians who fed them, Pavlov investigated whether he could "condition" the dogs to salivate in response to other unrelated stimuli. After repeatedly hearing a bell during mealtime, the dogs learned to salivate whenever it chimed.

What do Pavlov's dogs have to do with fear? It turns out that just as Pavlov's dogs learned to salivate, animals and humans learn to fear. When afraid, rats and mice show increased heart rate and blood pressure, and they freeze all movement, perhaps in an attempt to hide from predators. Researchers have conditioned mice and rats to freeze with fear when they hear a tone that they learned to associate with a mild shock. Researchers in the 1920s also showed that humans can be conditioned to fear everyday items associated with a loud noise.

Fear conditioning occurs outside the laboratory as well — we all have fears based on experience. For example, many children learn to fear the doctor's office where they previously received a shot. Although this fear memory and many others are relatively benign, some traumatic events like natural disasters, war, violent attacks, and serious accidents can cause lasting associations and effects that interfere with daily life.

Identifying brain processes involved in fear memories and learning how to disrupt them

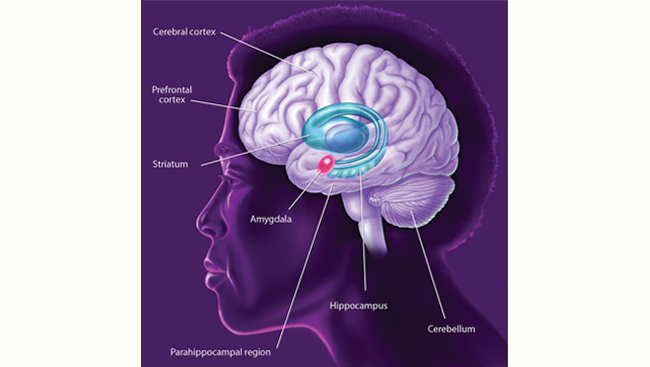

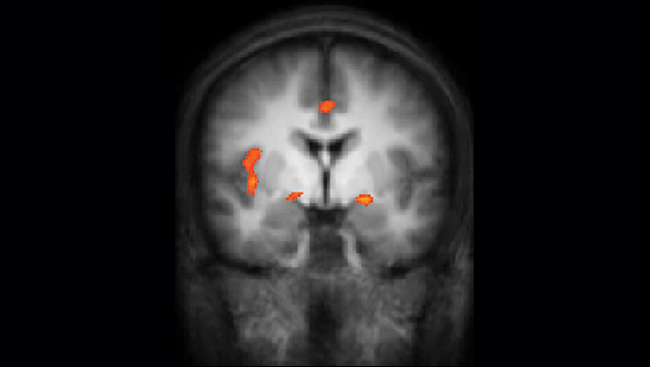

To find out how the brain processes fear, researchers lesioned brain regions and circuits in laboratory animals. When they lesioned a region called the amygdala, the animals failed to associate a neutral stimulus, like a tone, with a fearful event, like a shock. Furthermore, people who had surgery to remove the portion of the temporal lobe that contains the amygdala, a treatment for some forms of epilepsy, had difficulty learning to associate a flash of light with an unpleasant noise.

Making the association between a neutral stimulus and a frightening event is a learning process. In fact, brain cells in the amygdala show electrical and chemical changes that are associated with learning in other parts of the brain. However, unlike some other types of learning, lasting fear memories can be acquired quickly, often after a single experience, and can last a lifetime.

These findings suggest that fear is a special type of learning and memory. Rewriting fearful memories or forgetting them altogether might therefore help conquer fears. In fact, a common therapeutic technique to counsel people with phobias and PTSD is called memory extinction — patients are repeatedly exposed to formerly frightening stimuli in a safe environment, without harmful consequences. However, many people experience relapse after completing therapy.

Disrupting Fear Memories

Recent animal research points to more promising techniques to change fear memories. Two research groups have shown that treatments that affect enzymes called kinases are effective in disrupting fearful memories in rats and mice if they are given when the fearful memory is recalled, during a stage of memory called reconsolidation. The idea is that memories are written and rewritten every time we recall them, so modifying the brain's memory machinery during recall might change a memory for good.

One research group found they could disrupt fear memories in rats without drugs by conducting extinction therapy during memory reconsolidation. After training the rats to associate a tone with a shock, the researchers reactivated the memory by playing the tone. Then they waited several hours and replayed the tone over and over without any accompanying shock. Surprisingly, this drug-free therapy permanently disrupted the fearful association.

Understanding and treating PTSD

Research suggests that normal fear memory may go awry in people with PTSD. Up to 7.7 million Americans suffer from this punishing disorder in a given year as a result of traumatic experiences, including natural disasters, violent attacks, and war.

Until now, there have been few treatment options available to people suffering from PTSD. Many try cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which teaches new ways to think about and cope with symptoms. Others are prescribed antidepressants or try a combination of medication and CBT.

But as researchers learn how fear memories are encoded in the brain, and as animal research helps to identify new treatments, there may be new therapeutic options.

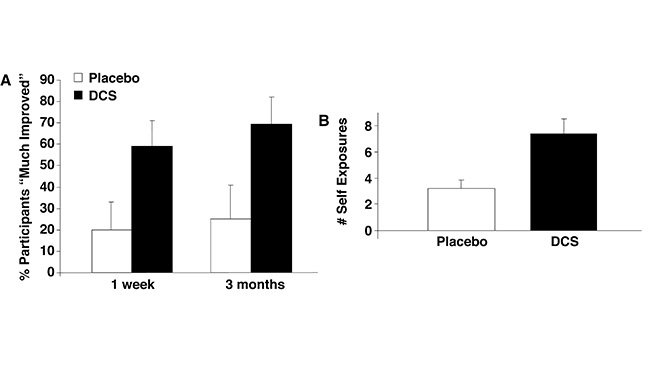

One new treatment is the antibiotic D-cycloserine. This drug activates receptors in the amygdala that are important in extinction. Studies in rats show that D-cycloserine accelerates extinction of fear memories. In a small clinical study, people with acrophobia (fear of heights) who took D-cycloserine in combination with CBT fared better than those who tried CBT alone.

Keep the Memory, Lose the Stress

Traumatic events activate the body’s stress response, strengthening and coloring subsequent memory. Some researchers are testing the idea that reducing the body's emotional response during the reconsolidation of frightening memories might reduce or prevent PTSD.

Drugs called beta blockers are used to treat people with high blood pressure — they stabilize the body's response to a stressor, preventing the fight-or-flight response. A recent human study showed that, when given during recollection of a frightening memory, the beta blocker propranolol reduced fear but did not affect knowledge of an event. Researchers are currently evaluating propranolol's ability to prevent PTSD in trauma patients.

These promising results would not have been possible without basic scientific research, funded in large part by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, and the Department of Defense. By uncovering the biological basis for fear memory, these studies are paving the way for new clinical therapies, approaches that may offer hope to people with PTSD.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org