Three-Layer Retina

- Published10 Jul 2017

- Reviewed10 Jul 2017

- Author Alexis Wnuk

- Source BioInteractive

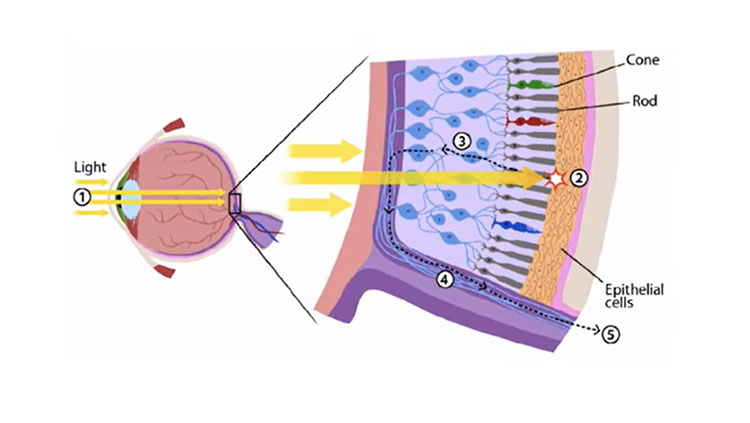

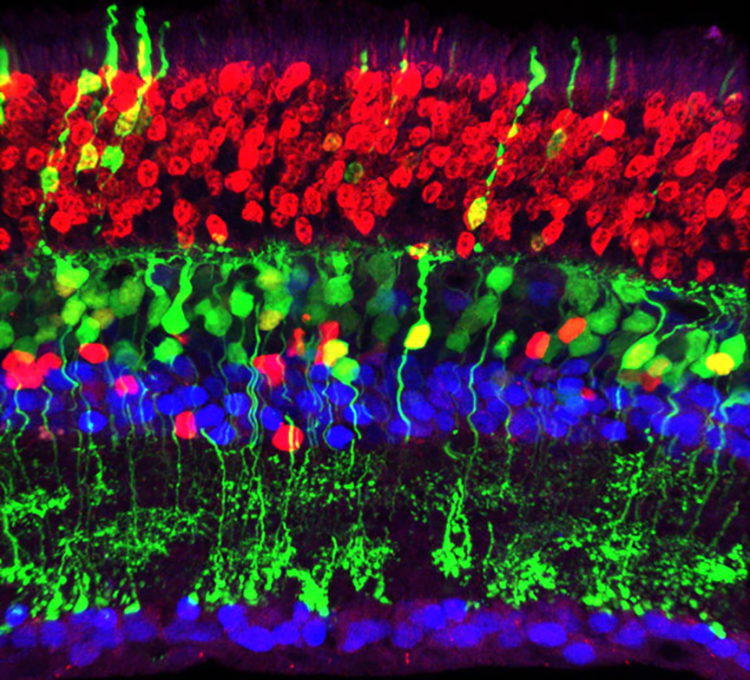

When light from the outside enters the eye, it’s focused on the retina, a thin film of nerve tissue lining the back of the eyeball. In the mouse, it’s no thicker than 0.5 mm, about the width of three sheets of paper.

Observing the mouse retina through a microscope reveals a structure like a three-layer cake, with each layer made up of different nerve cells that sequentially receive, process, and relay information. But the arrangement of the layers is the reverse of what one might expect.

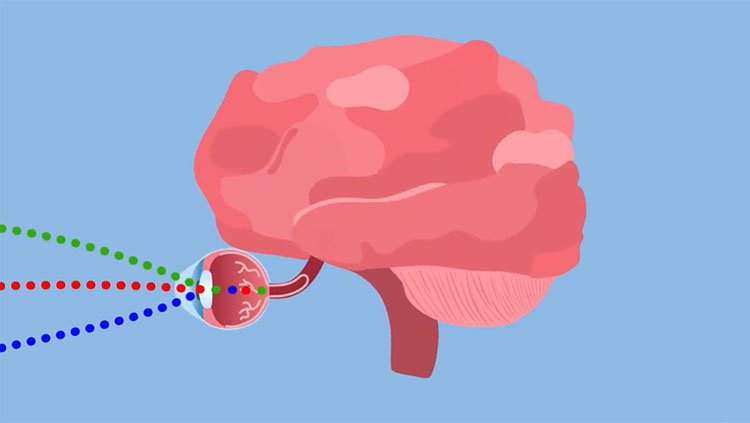

The cells that detect the light, the photoreceptors, are in the layer at the back of the eye (which is the top of this image), so that incoming light travels through the other two layers to reach them. The red-colored photoreceptor cells in the image are the rods, which detect dim light. The cones, which detect bright-colored light, are the other type of photoreceptors (not shown). Like a relay station, the long bipolar interneuron cells (colored green) spanning the middle layer, receive the signals from the photoreceptors and transmit them to the ganglion cells (blue) in the front retinal layer (bottom of the image). Two other types of cells in the middle layer—the horizontal interneurons and amacrine cells, both colored blue—also contribute to processing and relaying visual information. From the ganglion cells, signals then travel through the optic nerve to the visual areas of the brain.

All vertebrate eyes, from mice to humans, share this basic three-layered structure of the retina, which allows us to see the world around us.

This article was originally published on BioInteractive.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BioInteractive