Savor the Moment: The Peculiar Connection Between Taste and Memory

- Published6 Aug 2015

- Reviewed6 Aug 2015

- Author Michael W. Richardson

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Can the taste of your favorite food transport you back to childhood? Restaurateur and former Top Chef contestant Bryan Voltaggio thinks so. At Neuroscience 2014, Voltaggio offered a philosophy on cooking routed in brain function: Make original dishes that still carry all of the emotional weight of the classic foods used as inspiration. The goal “is to create a memorable experience, and one that connects not only me to the diner, but also the diner to a time, or a place, or a memory,” Voltaggio said.

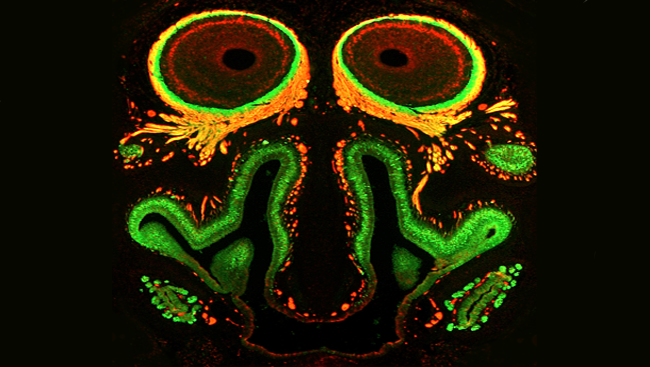

This image may look like a carnival mask, but it actually shows the key structures mammals use every time they smell. The “mouth” is the nasal cavity of a mouse, which is lined with specialized odor-sensing cells (in green). These cells signal to the olfactory bulbs — the round “eyes” in the image.

In striving to create this culinary experience, Voltaggio takes advantage of a feature of our brain that ties the flavor of food to intense emotional memories. During the Dialogues Between Neuroscience and Society lecture, an annual event that explores how neuroscience intersects with the world around us, Voltaggio served up tasty treats to a panel of neuroscientists and discussed the role the brain plays in the rich sensory experience that takes place every time we eat.

The Biology of Taste and Smell

Voltaggio and other chefs engage all of the basic senses in order to create a rich dining experience. But two of those senses, taste and smell, play the largest roles. Taste and smell are both senses that react to chemicals in food, and the oral and nasal cavities are directly connected, so it’s no surprise that the two senses are closely linked. When these senses work together to identify chemicals in food or drink, we develop what we know as flavor. Flavor is a sensation that uses many senses at once — an amalgam of taste, texture, temperature, and smell of whatever it is we are eating.

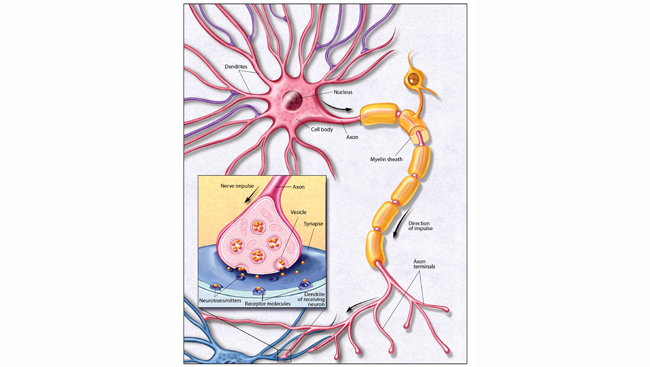

When you take a bite of something like fresh-baked bread, the taste buds on your tongue and mouth collect information about the chemical makeup of that dish. Each taste bud is made up of around 50 to 100 cells called gustatory receptor cells. When these cells are activated, they send signals to an area of the brain called the insular cortex, also known as the gustatory cortex, which makes us conscious of the perception of taste.

Taste buds can differentiate between the five basic tastes: salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and umami (a savory taste found in foods like mushrooms or steak). While these are important building blocks for our understanding of flavor, eating would be pretty boring if we could only pick up on five varieties of food. That is where smell comes into play.

The human olfactory system has more than 12 million smell receptors located throughout the nose and nasal cavity. These receptors collect odor molecules from the air and send electrical signals to a small structure in the brain called the olfactory bulb to be processed. Humans have 450 different types of smell receptors, each of which can detect slightly different smell molecules. Typically, what we think of as a single smell or flavor contains many types of discreet smell molecules, and there are millions of potential combinations. It’s this sense that can really tell the difference between store-bought sauce and your grandmother’s closely guarded secret recipe.

Remembrance of Flavors Past

Smell’s role in flavor is the reason that food has such a strong potential for calling up memories. Though the processes behind involuntary memories are somewhat mysterious, it seems to be related to the relative locations of some key brain structures. Both the olfactory bulb and the insular cortex are closely connected to the amygdala, an area involved in emotional learning. The olfactory nerve is similarly close to the hippocampus, one of the most important brain structures for memory.

The many connections between the olfactory system and the regions responsible for emotion and memory tie these experiences together. In fact, these areas are so closely related that studies have found that damage to areas of the brain responsible for memory can also harm one’s ability to smell.

While scientists know that emotional memories are encoded in the brain for longer periods of time, they are unclear as to the exact mechanisms behind this. However, it is clear that this ability has an evolutionary benefit.

Consuming food is always a gamble — wild berries or vegetables that our ancient ancestors gathered could easily be poisonous, and many foods go rancid quickly. Our brains mitigate this risk through the long storage of emotional memories. If you become sick after consuming a particular type of food, that flavor can cause disgust or nausea every time you try to eat it again. This is called taste aversion, and it can last for years, reducing the possibility that you’ll make the same mistake twice.

But what started as a survival technique has become an additional way to enjoy our food, as we are able to recall positive emotional memories associated with food, not just negative ones. When Voltaggio served his panelists mock oysters, a dish that simulates the taste, smell, and texture of the mollusk, he wasn’t just playing with expectations. He was exploiting a byproduct of our evolution to evoke all the oysters that came before and create a truly memorable meal.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN