Finding the Truth Behind Funny

- Published11 Apr 2019

- Author Jesse Klein

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

When Robert Provine first decided to study laughter a little more than two decades ago, he developed a very simple protocol: He would invite people into the lab, present them with videos of the best comedy sketches available, and record their laughter. It didn’t work.

Rather than observing fits of uncontrolled laughter, Provine and his colleagues found people laughed a little politely, if at all. Truth be told, the best laughs usually have nothing to do with great jokes.

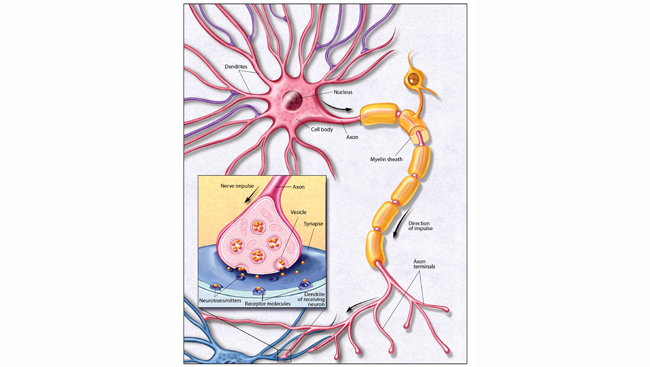

“It’s all automatic,” said Provine, a professor of psychology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “We don’t decide to laugh, it just happens. It’s one person’s brain communicating directly with another human’s brain.”

Provine, finds this phenomenon, called automaticity, “most striking when we laugh contagiously to the sound of another’s laugh, the basis of television laugh tracks.”

Without question, we can find ourselves cracking up, all by ourselves, at a truly funny sketch from a favorite late-night comedy show or viral video. But, Provine found we are 30 times more likely to laugh around others than by ourselves. And he did so not by bringing folks into the laboratory, but by observing laughter in its natural habitat, an approach Provine calls “Sidewalk Neuroscience.”

“Like Jane Goodall went to Gombe Stream reserve to study chimpanzees,” Provine said he spent his time in the field, quietly jotting down notes anytime someone laughed. “I found myself going to the student union, city sidewalks, and suburban shopping malls looking at humans in their natural setting, getting the collection of laughter to be analyzed.”

What’s more, Provine upended common belief when he found that laughter very rarely follows a joke. People laugh irrespective of whether or not humor is involved. Rather than solely a signal of hilarity, laughter serves as a building block for communication, punctuating speech at specific junctures. For example, laughter very rarely interrupts speech, instead coming before and after complete phrases.

“It tells us that laughter and speech are controlled by different mechanisms [in the brain] that are competing with each other,” Provine said. “And speech wins. Even congenitally deaf individuals produce vocal laughter. And when they laugh, they laugh according to the same principles as hearing people like at phrase breaks in signed speech.”

But laughter functions as more than the commas and exclamation marks for speech — it underpins social bonding in humans and other animals, says Sophie Scott, a speech researcher at the University College London. It cues others of our same species to join in the joke.

Humans, apes, and even rats all laugh. The heavy panting of chimpanzees and rats, characteristic of the sound of physical play, is actually laughter, and it indicates joy rather than aggression. Humans, on the other hand, laugh in a series of short, 75 millisecond notes while they exhale. What these various forms of laughter share is that they are an efficient and expansive way to bond and develop trust with members of our own species. But, laughter does more than that.

“Laughter is actually making us feel better,” Scott said. “It’s not just to show people that we like them.”

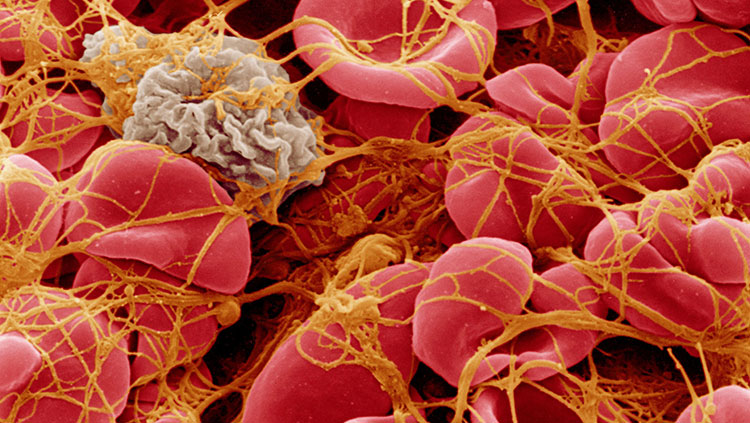

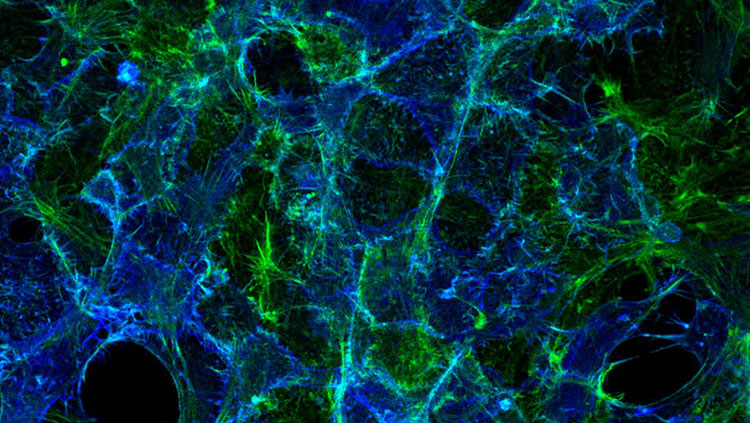

That’s because laughter appears to cause the brain to release naturally-produced, or endogenous, opioids. Researchers from Oxford University in England and Finland’s University of Turku and Aalto University determined this by scanning the brains of a dozen volunteers — not generally a laugh inducing environment.

“Laughter is one of those behaviors that disappears when you look at it in laboratory situations,” Provine said.

To combat this challenge, the English and Finnish researchers put participants in a PET scan only after they had spent time laughing with their friends. Compared to subjects who had sat alone in a room, the laughers had more opioids in the brain areas that promote the pleasurable feelings of togetherness important for social bonding.

People in the study who possessed more opioid receptors in their brains tended laughed more than the other participants. The data points to the opioid system potentially underlying the differences in sociability between people.

While we are far away from understanding everything about how laughter is produced, how it affects us, and the exact neurochemical mechanism, one thing is clear: Laughter is a powerful and deeply-rooted part of human behavior and communication.

“Laughter is universally recognized among humans, it’s a social vocalization that’s common to all humans,” Scott said.

And its universality underpins its importance as a field of scientific inquiry.

“Laughter earns its keep as a scientific problem. ‘Ha-Ha’ provides a simple systems approach to vastly more complex behaviors of speech and language,” said Provine. “Contagious laughter provides a low-tech entrée to the ‘mirror’ phenomena, and contrasts between human and chimpanzee laughter may even reveal why we can talk, and chimps can’t.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Caruana, F. (2017). Laughter as a Neurochemical Mechanism Aimed at Reinforcing Social Bonds: Integrating Evidence from Opioidergic Activity and Brain Stimulation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 37(36), 8581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1589-17.2017

Manninen, S., Tuominen, L., Dunbar, R. I., Karjalainen, T., Hirvonen, J., Arponen, E., … Nummenmaa, L. (2017). Social Laughter Triggers Endogenous Opioid Release in Humans. The Journal of Neuroscience, 37(25), 6125. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0688-16.2017

Provine, R. R. (2016). Laughter as a scientific problem: An adventure in sidewalk neuroscience. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 524(8), 1532–1539. doi: 10.1002/cne.23845

Scott, S. K., Lavan, N., Chen, S., & McGettigan, C. (2014). The social life of laughter. Trends in cognitive sciences, 18(12), 618–620. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2014.09.002