How Pregnancy Changes the Brain

- Published28 Feb 2018

- Reviewed28 Feb 2018

- Author Alexis Wnuk

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

From the moment a developing embryo implants in the womb, a woman’s body begins to undergo a slew of changes. Some are immediately apparent to the mom-to-be — a growing belly, fatigue, mood swings, and morning sickness, among others. What may not be so obvious are the changes happening in her brain.

“There are a huge host of adaptations a woman's body has to go through to allow for that fetus to grow,” says Liisa Galea, a neuroscientist at the University of British Columbia. Galea and other researchers are beginning to understand that those adaptations include changes to the structure and function of the woman’s brain.

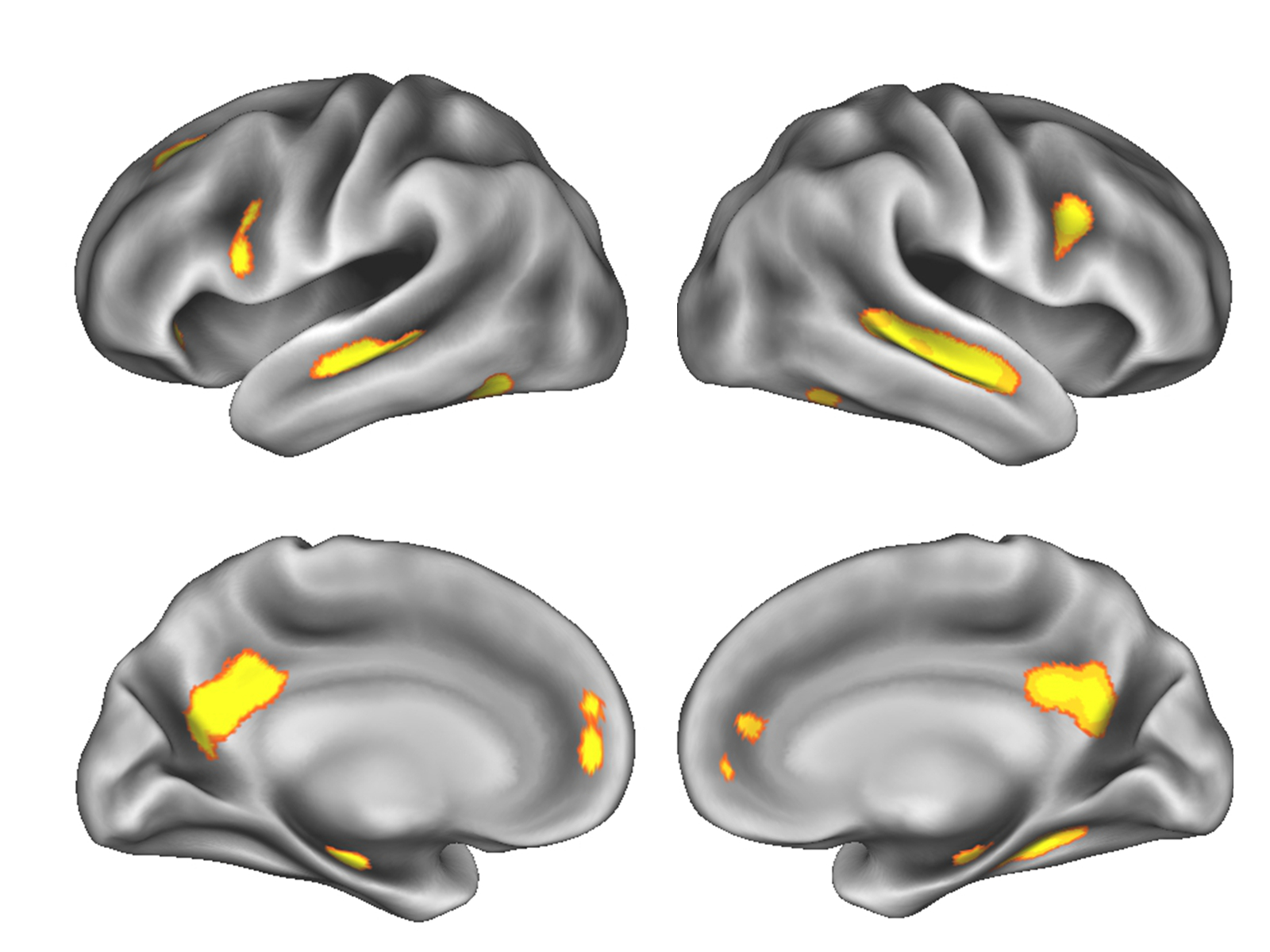

In 2016, a team of researchers from the Netherlands and Spain used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to study what happens inside the brain during pregnancy. Comparing MRI images taken before women became pregnant with images taken after they had given birth, the researchers found pregnancy shrinks the brain’s gray matter, the pinkish-gray tissue containing the cell bodies and synapses of nerve cells. What’s more, the volume loss persisted for at least two years after childbirth.

While losing gray matter might seem detrimental, the effect may be quite the opposite. “Everybody always thinks of volume loss as something negative, as a loss of function,” says Elseline Hoekzema, a neuroscientist at Leiden University in the Netherlands and lead author of the study. But volume loss can also represent a “fine-tuning of connections.” She compares the change to what happens in the teenage brain when a flood of hormones triggers widespread pruning of synapses, the connections between nerve cells. This makes for more efficient, streamlined brain circuits. Hoekzema notes, however, that they couldn’t say for sure whether synaptic pruning or some other mechanism — like loss of neurons or glial cells — was behind the gray matter shrinkage in pregnant women.

The areas of the brain that shrunk the most were those involved in social cognition, the ability to figure out what someone else is thinking and feeling. When a new mom was shown a picture of her baby, these areas of the brain lit up with activity. Enhanced social cognition might help a mother take care of her baby, enabling her to decode the child’s various coos and cries and figure out what she needs, Hoekzema says.

Improvements in social cognition might come at a cost. While studies looking at cognitive changes during pregnancy and the postpartum period have produced mixed results, many women report experiencing memory problems, a phenomenon termed “pregnancy brain.” Spatial memory, for example, might suffer late in pregnancy because it’s not critical for offspring survival during that time. Instead, the body redirects energy and resources to caring for the baby, Galea says.

Hormones like estrogen, progesterone, and others most likely drive the changes in the brain structure and function during pregnancy. Hormones can exert a powerful influence on brain cells, and no time in a person’s life produces more extreme hormone fluctuations than pregnancy. Yet, researchers have largely neglected how pregnancy and its hormone surges shape the brain — in the last century there have been only a few dozen studies exploring pregnancy’s impact on women’s brains.

“There’s just so little research on it,” Galea says. “It’s a significant experience in a woman’s life that we need to study more.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

What to Read Next

Also In Body Systems

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org