Animal Research Success: Prion Diseases

- Published9 Mar 2012

- Reviewed9 Mar 2012

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

In the mid-1980s, the infectious disease bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as “mad cow” disease, appeared in cattle in the United Kingdom. The disease affected their nervous system, making cows act strangely and eventually lose the ability to walk. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a related disease appeared in humans, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). These two outbreaks resulted in the death of more than four million cattle and affected 50 percent of Britain’s dairy farms. More than 200 people died as well.

Although genetic forms of CJD had appeared before, this outbreak was specifically linked to the consumption of contaminated beef products. But why did it take nearly 10 years before the disease showed up in humans? The reason lies in the length of the incubation period. In humans, symptoms may not show up for up to eight years after they are infected. This was the cause of the long gap between the outbreak in cattle and in humans. Over the years, animal studies have enhanced scientists’ understanding of these diseases, leading to strategies to prevent them.

Mad cow disease and CJD are similar to kuru, another human disease, and scrapie, which affects sheep. All four diseases do not have typical symptoms of fever and inflammation. Instead, they follow a more dangerous path. These diseases cause brain cells to die, leading to small holes in the brain. As a result, affected individuals have trouble coordinating muscle movements.

By injecting chimpanzees with extracts of kuru from people who had died from it, Carleton Gajdusek, MD, showed that the disease was caused by an infectious agent. For this discovery, he won the Nobel Prize in 1976.

Work with other animals led to more breakthroughs. Through experiments first conducted in mice, scientists discovered that these diseases could be transmitted before the animal showed any sign of the infection, and that genetics played a role in each animal's susceptibility to the diseases. Scientists then learned that they could perform similar experiments in a shorter period of time using fewer hamsters – the larger animals tended to develop the disease faster – so they switched animal models.

Stanley Prusiner, MD, winner of the 1997 Nobel Prize, realized that all four diseases were caused by the same agent – a protein that he termed prion, for protein infection. This was the first time an infectious disease was shown to be transmitted by something other than a virus or bacteria. All of these diseases, as well as others not discussed here, are now referred to as prion diseases.

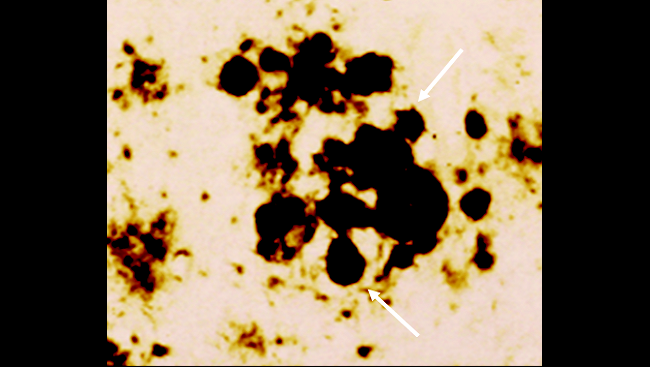

The prion protein is found in all animals in a three-dimensional shape, but when diseased, its shape changes. The diseased prion then induces other proteins of the same type to change shape. These misshapen proteins then spread throughout the brain. The prions clump together and form plaques that damage neurons.

Currently, there is no cure for prion diseases. However, researchers’ increased understanding of these diseases has had positive benefits for both humans and animals. Changes in cattle feeding methods, as well as breeding sheep more resistant to the disease, have dramatically decreased farm epidemics, which has led to fewer cases in humans.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Archives

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org