Sleep, Uninterrupted

- Published25 Jul 2018

- Reviewed25 Jul 2018

- Author Rachel Kaufman

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

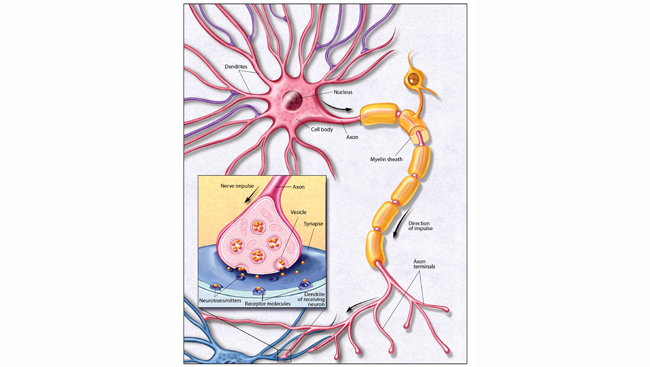

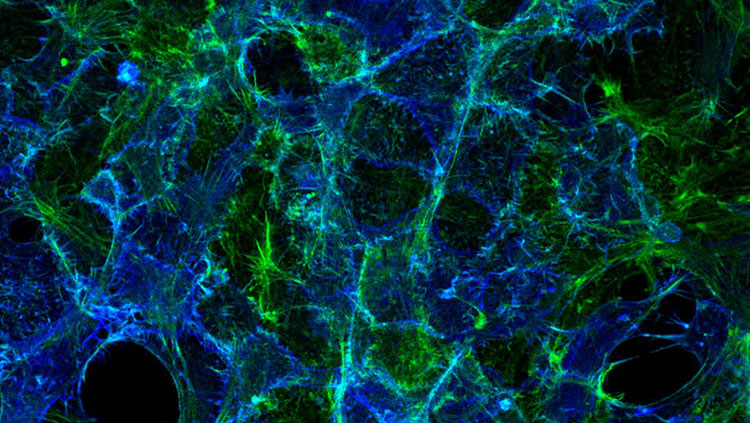

Whether you are a morning person or a night owl, your body maintains a daily rhythm. Hormones, blood pressure, coordination, alertness and other biological functions increase and decrease over the day in a repeatable pattern. And, like almost every plant and animal on earth, it operates over a nearly 24-hour period. In people, disruption to this “circadian rhythm” may contribute to chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease. And, as sleep-deprived parents and shift workers around the world can attest, disrupted circadian rhythms can alter mood.

The question is how? Psychiatrist and neurobiologist David Welsh, from the University of California, San Diego, is working on figuring that out.

Welsh and his team wanted to know if the brains of depressed and demoralized mice still maintained normal circadian rhythms. Test mice received random, unpredictable shocks in a procedure that can trigger a state of “learned helplessness.” Animals stricken with learned helplessness fail to attempt to escape the shocks because they had been unable to do so previously. The team then examined the brains of the mice, finding a striking difference between mice that displayed symptoms of learned helplessness. “If the mice are helpless, the brain is less likely to be rhythmic,” Welsh said.

Welsh’s work indicates that depression may disrupt circadian clocks in mice. But, his team wanted to know if disrupting a circadian clock could cause depression.

To do this, they studied mice that couldn’t produce a protein thought to be crucial for normal circadian rhythm. Those mice “looked more depressed right out of the gate,” Welsh said. The mice also gained weight, just like many depressed humans do.

Welsh’s research may help us understand and ultimately treat or prevent mood disorders in humans. Humans who have a “weaker” internal clock may be more susceptible to circadian disruptions, Welsh said. If you then add the additional challenges of jet lag, shift work or other factors that affect sleep patterns, you’ve got a recipe for problems.

It’s understandable that traumatic experience could have wide-ranging biological effects on an animal, and how poorly functioning circadian rhythms may lead to mental and physical disease for the individual suffering from such a problem. However, Yasmine Cisse from The Ohio State University discovered something more troubling: A person with skewed circadian rhythms can pass health problems on to his or her children. Cisse studied Siberian hamsters, exposing them to dim light at night. Hamsters are nocturnal, so the dim light does not affect their sleep, but it does disrupt their circadian rhythms. After eight weeks of light exposure, she paired up the hamsters to mate. In some pairs, both parents had been exposed, to the dim light, in others, only one parent had been exposed and in a third group, neither parent had light exposure. These hamsters mated, and their baby hamsters grew to adulthood.

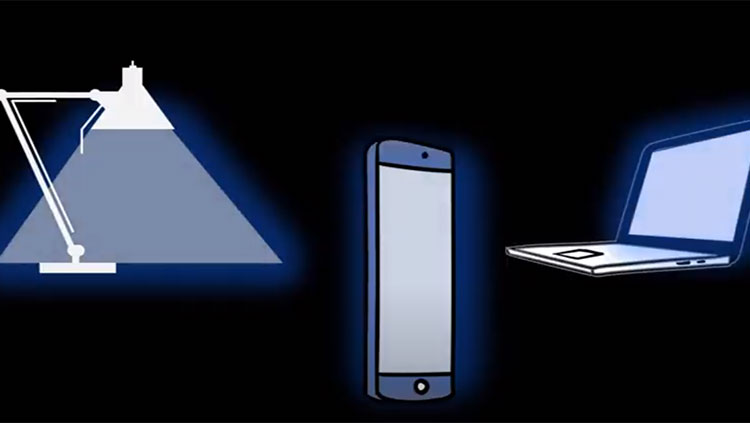

The results were striking. Offspring of mothers that had been exposed to dim light at night displayed more depression-like symptoms. And, offspring with either one or both parents exposed to the light had weakened immune systems. The light was fairly dim: “We liken it to the amount of light you would get from a nightlight about a meter away from your face,” Cisse said. But even this small amount of light seems to have significant consequences for the hamsters and their offspring.

The findings could spell trouble for people who spend lots of time looking at bright screens at night. “People have a way of thinking that [circadian disruptions] only affect them, and hopefully this will sort of put things in perspective. It’s not just affecting their health, but it could have future implications for their children,” said Cisse. “There’s no way we’re going to turn off our phones at sunset, but the big takeaway is to maintain proper circadian hygiene. When you do turn everything off, let it be off.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN