Motherhood and the Brain

- Published30 Jan 2018

- Reviewed30 Jan 2018

- Author Rachel Kaufman

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Although more than 200 million women become pregnant each year, little is known about how pregnancy and motherhood affect women’s brains. Yet, these experiences entail “unparalleled hormone surges” that affect the entire body, including the brain, says Elseline Hoekzema, a researcher at Leiden Institute for Brain and Cognition.

Hoekzema and her research team studied physical changes in (human) moms’ brain structure by scanning the brains of about 80 men and women, more than half of whom hoped to have their first child. After the women gave birth, the team scanned everyone's brains a second time, and a third time after their children’s second birthday.

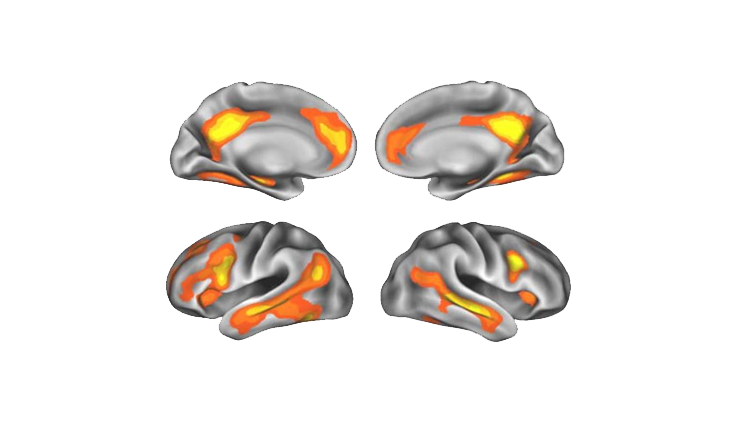

She presented their findings at the Neuroscience 2017 meetings: Moms’ brains changed so uniquely that a computer algorithm easily sorted which brain scans belonged to women who had gone through pregnancy and which did not. Notably, the gray matter around areas of the brain associated with “theory of mind” (ability to consider others’ mental states) had shrunk in the brains of women during pregnancy, and remained shrunken two years later.

Teenagers undergo a similar process. During puberty, teenagers are awash in hormones, much like pregnant women, and their brains are shrinking – also like pregnant women. Yet, in teens, this change is known to be “a very essential process of fine-tuning, which leads to more efficient neural networks," says Hoekzema. A similar thing may happen in new mothers: As their brains change, neural pathways underlying social intelligence may become more efficient. “This may help a woman prepare for being a mother,” Hoekzema suggests.

Researchers also use animal studies to learn about motherhood.

Two studies from the Froemke Lab at NYU School of Medicine, presented at Neuroscience 2017, examined how mouse brains respond to baby calls. Baby mice separated from their mothers emit ultrasonic calls. Mother mice hearing these calls retrieve their pups and bring them back to the nest. However, mice that have not given birth ignore the calls (researchers know that non-mom mice hear the calls, because an unrelated experiment tested their hearing).

Postdoctoral researcher Silvana Valtcheva played recorded baby mouse calls to mother mice and to mice that were not moms, while measuring their brain responses. In brains of mother mice, neurons lit up in a region called the paraventricular nucleus, but nothing happened there in brains of non-moms. The paraventricular nucleus is important as a place that makes oxytocin, a hormone involved in (among other things) mother-child bonding. These findings might help us understand how human moms bond with their babies.

Interestingly, mice don't have to be moms to have “maternal-looking” brains and behavior. Mice that spend time with a mom and her litter are known to start acting like "babysitters": They fetch crying baby mice, like mother mice do. According to Jennifer Schiavo, a PhD candidate in the Froemke lab, these babysitters’ brains change, too!

For her study, Schiavo generated a series of fake baby mice cries that resembled, but differed slightly from, the cries of real baby mice. Fake cries were faster or slower, or had a different pitch than authentic baby mouse cries, simulating the fact that no baby sounds exactly like another baby. Researchers played those cries, along with real cries, to three categories of test mice: mom mice, "babysitter" mice and mice that never gave birth or spent time near babies.

In mother mouse brains, neurons in the auditory cortex – the brain region that translates signals from our ears into what we hear – reacted to a variety of baby mouse calls, the fake "close enough" ones and the real ones. Mice that had never given birth or spent time around babies reacted only to real cries. But if mice from this latter category were housed with a mom and her pups, their brains started responding to baby mouse cries in a way almost identical to mother mice. About 24 hours later, these mice began acting like “babysitters.”

Schiavo compares this process to learning English. "If I say 'hello' slowly or quickly, you still understand me." Someone who doesn't speak English might have trouble understanding a fast hello, or hello spoken with an accent, but as they study more their brain adapts. Similarly, these mice are learning that babies can sound different from one another, and their brains change to accommodate that fact. The research, Schiavo says, is an example of "experience-based plasticity," how experiences change the brain, and may also elucidate how brains change when people become parents.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Also In Diet & Lifestyle

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org