Roll Over, Sit, Lie Still in the MRI: How Brain Imaging Helps Us Understand Dogs

- Published21 Feb 2019

- Reviewed21 Feb 2019

- Author Linda Lombardi

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Gregory Berns spends a lot of time patiently coaxing dogs with treats to lie down, place their chins on a chin rest, and stay very, very still. It’s training for the day when he will ask them to hop into an MRI scanner.

For a human, having an MRI is akin to laying in a closed coffin next to a roaring jet engine. For dogs, with their ultrasensitive hearing, the experience can be terrifying.

“What we’re asking the dogs to do is very simple — it’s just, lie down. It’s a natural behavior,” says Berns, a neuroscientist at Emory University whose team has trained 100 dogs thus far. “The challenge is really about the environment we’re asking them to do it in, which is an MRI scanner.”

Berns and his team are painstakingly training these dogs to put a simple notion to the test. They are asking: How does the dog mind work? And, can we see emotion in a dog’s brain? In effect, what is it like to be a dog?

In asking these questions, it’s important to Berns that the dogs he studies are willing volunteers. And so, armed with plenty of snacks, the researchers use positive association to get them used to the position they will take. To acclimate them to the noise, they make positive association between playtime and the sound of the MRI. They also fit them with ear protection to dampen the more intense sounds.

“To get anything useful out of their brains, of course we want them awake,” he says. “And I think it’s unethical to sedate them and anesthetize them because that means by definition that they don’t want to be there.”

Scientists tend to be leery of attributing emotions to animals. People can use words to describe how they’re feeling but dogs and other animals simply cannot. Even so, scientists know that emotions arise from the brain, and studies of the human brain and emotions can provide a starting point to examine a dog’s brain.

“We use human experiments as a reference point for interpreting what happens in the dog’s brain,” Berns says.

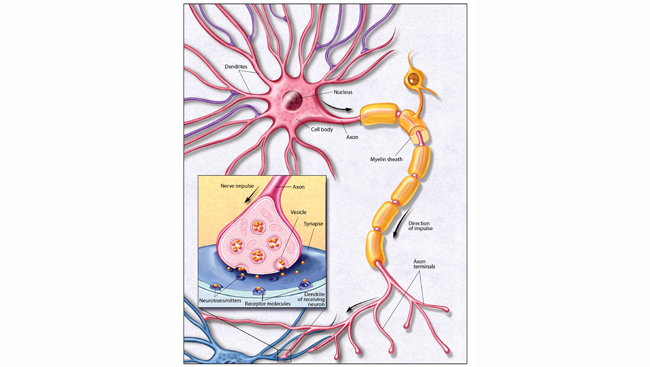

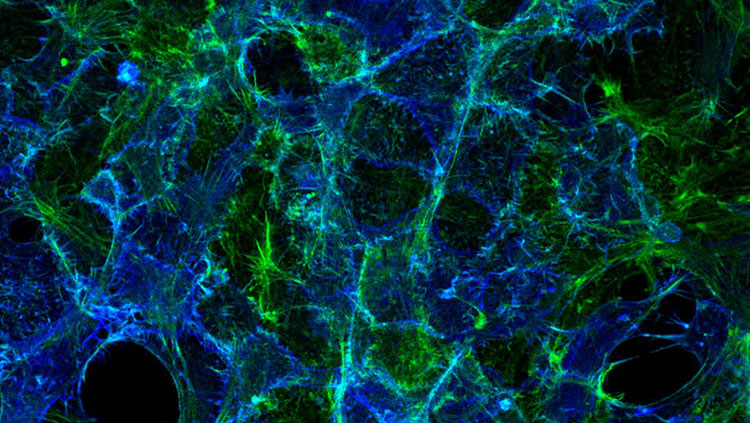

Berns’ lab employs a specific form of scanning called fMRI, which measures blood flow in the brain. Presumably, areas with an increase of blood flow are active. The team has used fMRI to predict whether a dog is a good candidate for service work. They also discovered a region in the temporal lobe of the dog brain dedicated to face processing similar to the region found in humans and other primates.

Compared to people, dogs possess a heightened sense of smell. Berns’ team wondered how dogs would respond to the scents of familiar people as opposed to a stranger, and a known dog compared to an unknown one. The researchers looked for activity in the caudate nucleus, which is part of the basal ganglia. In humans, the caudate nucleus, as a component of the reward system, lights up in anticipation of something desirable. Though researchers expected the dogs’ caudate nuclei to respond most strongly to the smell of the familiar dog, they found that the response was strongest when the dogs sniffed the scent of a familiar person.

Does this mean dogs like their owners, or is it just the result of associating them with dinner? Turns out, the dogs’ feelings for their owners aren’t just about the food. The researchers tested this by teaching dogs that seeing one object meant they’d get a treat, and seeing a different object meant that their owner would appear and praise them. In about three-quarters of the dogs, the caudate response was as strong or stronger to their owner speaking to them.

If dogs crave their owners’ praise and attention, is it possible that they could become jealous when another dog gets food or attention? Berns’ team looked to activity in the dogs’ amygdalas, which are associated with arousal, to see if dogs feel something like jealousy. The dog’s owner would either put a treat in a bucket or give it to a realistic-looking statue of a dog. Reactions differed depending on the dog’s temperament: as Berns puts it, they “clearly differentiated the fake dog getting food versus the bucket, and it was most salient to the dogs with aggressive tendencies.”

While fMRI is a powerful tool to understand the brain, exactly how you ask your question matters. Some researchers are skeptical of the jealousy experiment, which was modeled after a previous study that analyzed dogs’ behavior. Alexandra Horowitz, who leads the Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard College, says that studies using a fake dog are problematic since dogs quickly figure out the trick. “So, what these experimental designs are doing is asking what dogs do when their owners interact with a toy that they know isn’t a dog,” she says, and that doesn’t reveal anything about jealousy: “No one is jealous of the newspaper for being read by one’s friend.”

But that objection is equally true whether behavior or brain activity is being analyzed, and Berns believes that behavioral studies with dogs have weaknesses as well. It’s particularly tricky when studying emotions, since the same emotion can result in different behaviors, and the same behavior can be the result of different emotions. “But on a deeper level, behavior is just the tip of the iceberg — it’s just the outward manifestation of what’s going on in the dog’s head,” he says. “What I’m particularly interested in is what’s going on in the dog’s head.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Alexandra Horowicz. (n.d.). Retrieved February 21, 2019, from https://alexandrahorowitz.net/

Berns, G. S., Brooks, A. M., & Spivak, M. (2014). Scent of the familiar: An fMRI study of canine brain responses to familiar and unfamiliar human and dog odors. Behavioural Processes. Retrieved February 21, 2019, from DOI: 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.02.011

Cook, P., Prichard, A., Spivak, M., & Berns, G. S. (n.d.). Jealousy in dogs? Evidence from brain imaging. Animal Sentience, 22(1). Retrieved February 21, 2019, from https://animalstudiesrepository.org/animsent/vol3/iss22/1/

Cook, P. F., Prichard, A., Spivak, M., & Berns, G. S. (2016). Awake canine fMRI predicts dogs’ preference for praise vs food. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(12), 1853-1862. Retrieved February 21, 2019, from doi: 10.1093/scan/nsw102

Cook, P. F., & Berns, G. S. (2018). The degeneracy of behavior and the rise of neuroimaging to measure affective states in dogs. 3(22), 23rd ser. Retrieved February 21, 2019, from https://animalstudiesrepository.org/animsent/vol3/iss22/23/

Gregoryberns.com. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://gregoryberns.com/

Horowicz, A., Franks, B., & Sebo, J. (n.d.). Fill-in-the-blank-emotion in dogs? Evidence from brain imaging. Animal Sentience, 3(22). Retrieved February 21, 2019, from https://animalstudiesrepository.org/animsent/vol3/iss22/20