The Postpartum Is a 'Perfect Storm' for Depression

- Published6 Jul 2018

- Reviewed6 Jul 2018

- Author Alexis Wnuk

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Everything changes the instant a baby arrives. That’s especially true for a new mom. While both mom and dad will see day and night upended by a seemingly endless cycle of crying, nursing, burping, and changing, mom is undergoing dramatic physical changes as well.

The moment the placenta is expelled, levels of hormones like estrogens and progesterone come crashing down, returning to pre-pregnancy levels within a week. Those hormonal changes, coupled with the stress of caring for an infant, might make the postpartum period a “perfect storm” for mental health problems like depression, says Liisa Galea, a neuroscientist who studies how hormones affect the brain.

What’s more, the depression that develops during this period of heightened vulnerability may be very different from depression occurring at other points in a woman’s life.

As many as three in four women feel depressed or anxious in the first few days after delivery. These “baby blues” typically resolve within two weeks. Postpartum depression is different. Symptoms, which include profound sadness, crying, fatigue, and changes in appetite, can emerge at any time within the first year after delivery and persist for at least two weeks. And when they do, postpartum depression can impair the normal bonding between mother and infant, and may even lead to cognitive and emotional problems in offspring later in life.

In 2001, Galea and her colleagues at the University of British Columbia developed the first model of postpartum depression in rats. The team simulated pregnancy by delivering a cocktail of pregnancy hormones to female rats for 24 consecutive days, the length of gestation in rats. On the 25th day, the researchers stopped giving pregnancy hormones to some of the animals. Those animals, when placed in a tank of water with no escape, gave up trying to escape faster than rats continuing the hormones. This test uses the willingness to give up as an indication of depressive symptoms.

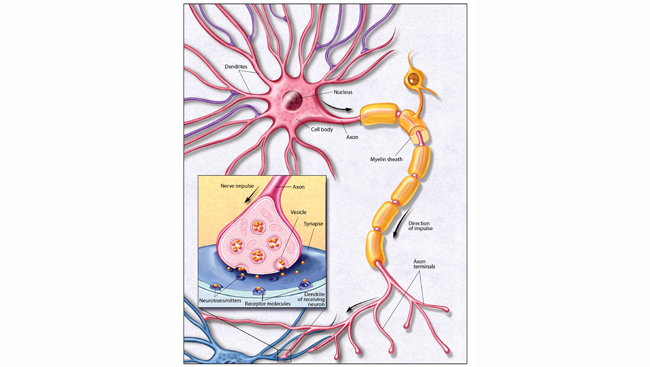

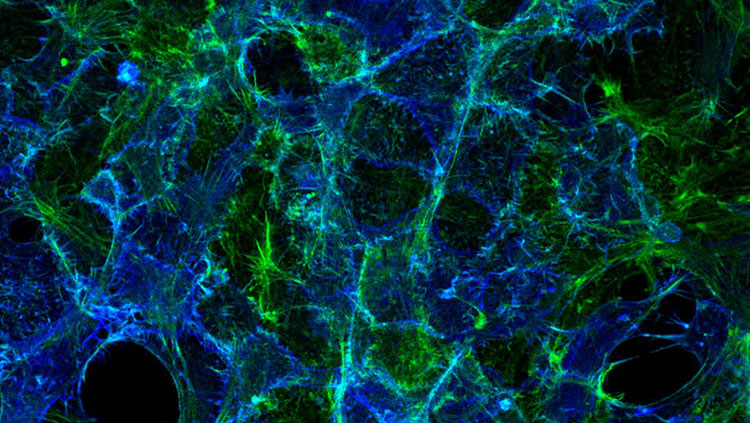

There is more at play in postpartum depression than just plunging hormones — pregnancy also physically alters the brain. During pregnancy, the brain’s gray matter — the pinkish gray tissue dense with neuron cell bodies — shrinks and doesn’t return to its pre-pregnancy size until months later. One of the regions that shrink is the hippocampus, the seat of learning and memory, an area that is smaller in people with major depression compared to healthy adults. In the postpartum period, the hippocampus also loses some of its plasticity — its ability to adapt and reroute connections between nerve cells, according to research conducted by Galea.

Depression disrupts the typical patterns of brain activity. Postpartum depression does too, but, in different ways. Jodi Pawluski, a neuroscientist at the University of Rennes 1 in France, reviewed studies examining these differences in brain activity. One of the key findings concerned the amygdala, the brain’s emotional center. In women with major depression, the amygdala was hyper-responsive to emotional words and pictures. Women with postpartum depression had underactive amygdalae.

There’s even evidence suggesting postpartum depression — or perinatal depression, a more inclusive term for depression occurring any time during pregnancy and the early postpartum — is a spectrum of disorders. In a study published in 2017, researchers analyzed the symptoms of more than 600 women with perinatal depression and identified five distinct subtypes of the disorder.

Studying these kinds of distinctions can help us understand the disorder and the best possible ways to treat it, says Galea.

Pawluski shares this sentiment. She says people often ask her how postpartum depression or antidepressant medications affect the offspring. “Sometimes I think we spend a lot of time asking, ‘What about the offspring, what about the kids?’, and we're not spending enough time asking, ‘What about the mom?’”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN