Glioma Brain Tumors

- Published16 Jun 2008

- Reviewed15 Oct 2012

- Author Debra Speert, PhD

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

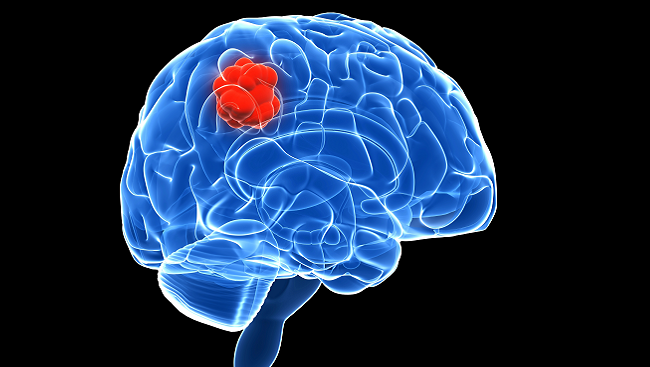

For years, researchers puzzled over an aggressive form of brain cancer. The lethal glioma tumors often outsmart traditional cancer treatments such as surgery, and quickly invade healthy brain tissue.

Brain tumors always have been one of the most devastating diseases because they are so difficult to treat, much less cure. But now scientists are on track toward finding what may be definitive treatments for the most virulent of these tumors.

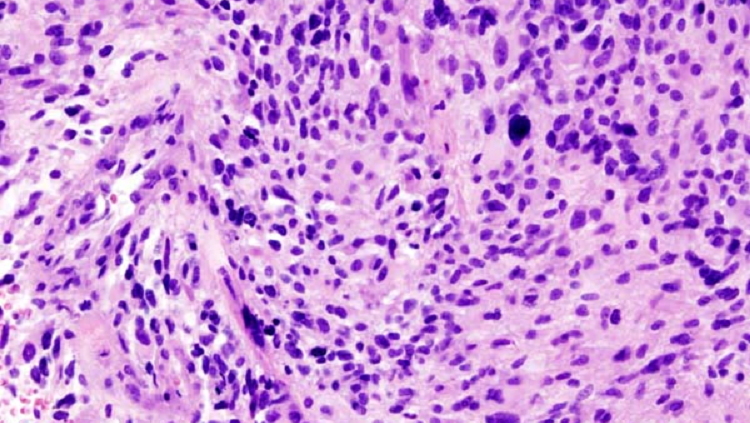

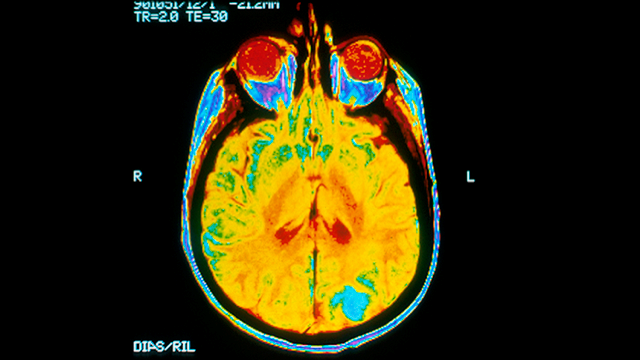

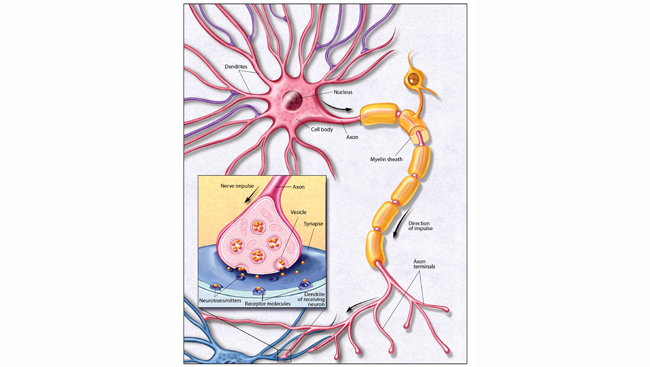

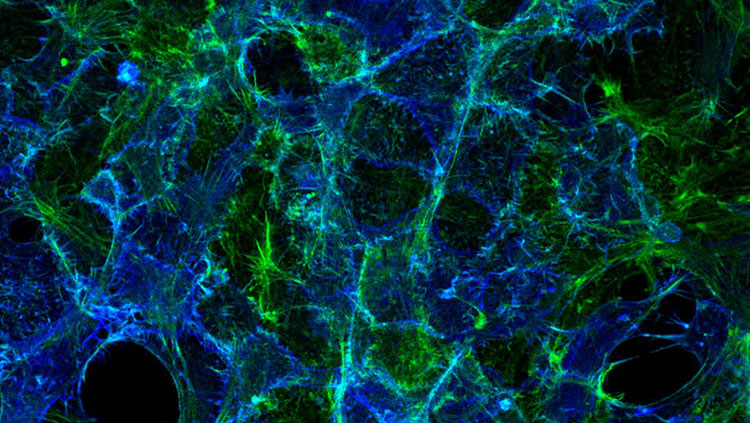

Most brain tumors develop from cancerous glial cells and are called gliomas. Unlike other cancers, glioma tumors grow in the confined space inside the head. In order to grow, most cancers push healthy cells aside, but due to space constraints, glioma tumors must destroy normal brain cells. To kill healthy nerve cells, glioma tumors release large quantities of the neurotransmitter glutamate. Excess glutamate is toxic to neurons and causes seizures in up to 80% of people with gliomas. Depending on the tumor's size and location, other symptoms include paralysis, behavior changes and dizziness.

A glioma tumor is particularly damaging because it tends to quickly sprout and spread within the brain. Each year, approximately 18,000 Americans find out that they have a glioma. Many die within 12 months.

Researchers have come closer to improving these odds by examining the biology of glioma tumors in animals and humans. Studies are uncovering the cancer's unique characteristics, including the mechanisms that help it survive and spread throughout the brain.

- The advances may help make the diagnosis less grim by leading to:

- Therapies that prevent gliomas from harming healthy brain cells.

- Methods that limit the spread of the cancer.

- Treatments that block the tumor's life-sustaining molecules.

Some scientists are devising therapies to limit the damage glioma tumors inflict on healthy brain cells. To release glutamate, glial cells must first import cystine, naturally formed from the fusion of two amino acids. The drug sulfasalazine, which is normally used to treat inflammation in the intestines, blocks cystine import and prevents glutamate release. Cystine is a precursor for glutathione, an antioxidant that may help glioma tumors survive chemotherapy. In animal studies, sulfasalazine reduced tumor size by over 80%. Clinical trials using sulfasalazine to treat gliomas in humans will begin soon.

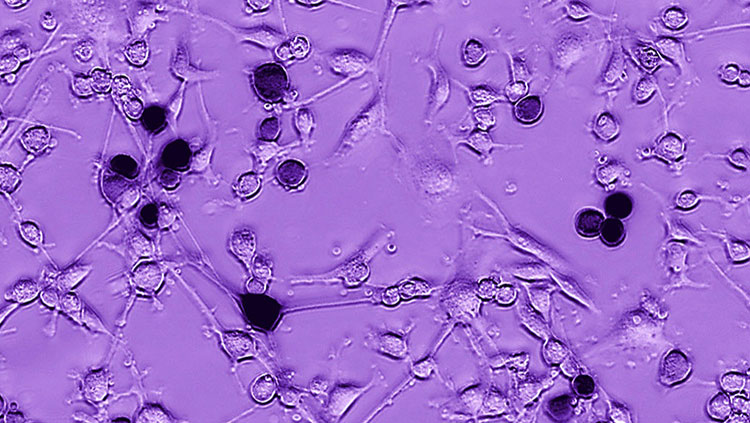

Other researchers are developing methods to inhibit glioma tumors from spreading throughout the brain. In order to expand, glioma cells break free by altering molecules that hold them in place (called extracellular matrix molecules), like the glioma-enriched protein BEHAB. To travel through the brain’s narrow spaces, glioma cells also undergo physical changes in size and shape, a process that involves ion channels like glioma chloride channels.

Targeting these molecules with a toxin could not only wipe out the cancer cells and spare the healthy cells, but also could impede the cancer cells’ expansion. Scientists discovered that chlorotoxin, a molecule from the venom of the giant yellow Israeli scorpion, specifically blocks glioma chloride channels, preventing glioma tumor expansion. And linking a poison to chlorotoxin kills glioma tumor cells without affecting healthy cells, according to tests on animal models and in cells in a petri dish. A synthetic version of chlorotoxin (TM-601) is currently in clinical trials in people.

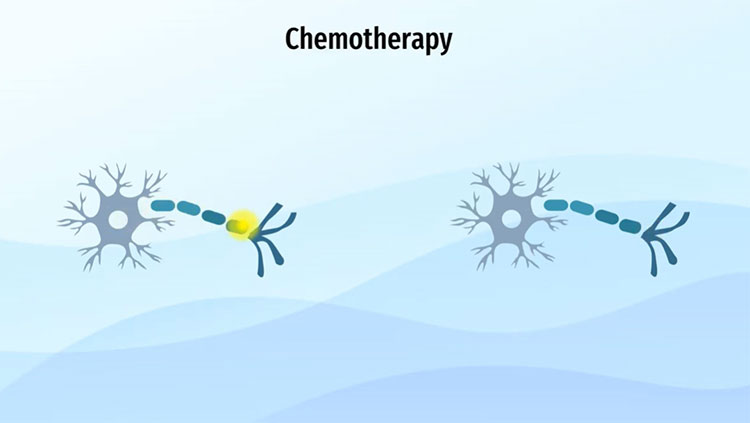

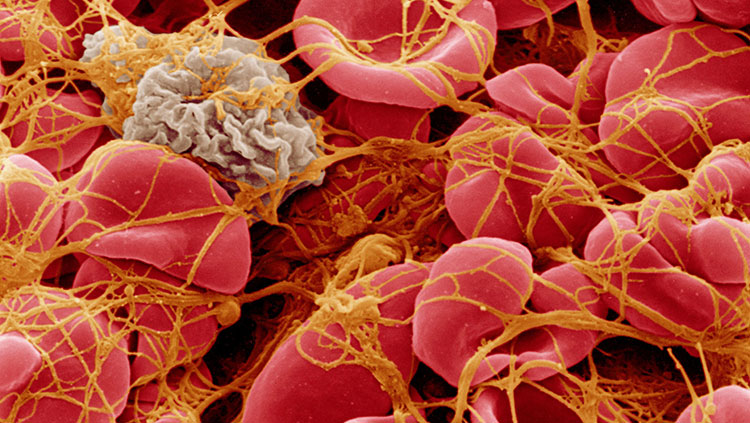

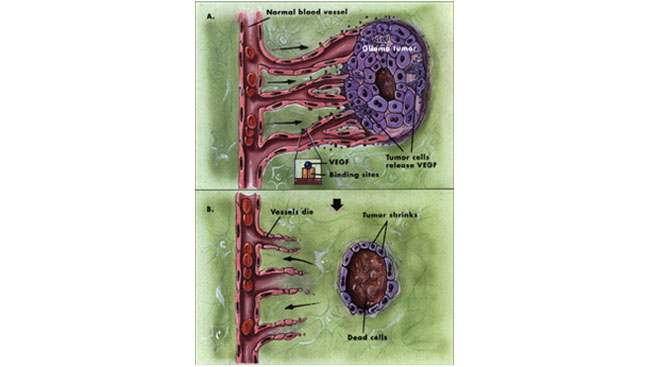

On another front, researchers are examining how blood vessels link up with glioma tumors to nourish them. Many scientists believe that disrupting the union will starve the tumors to death. The protein, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), is one target under investigation (see illustration). Researchers recently used a gene therapy technique to interfere with VEGF's activity at specific binding areas. Glioma growth was inhibited by 90 to 95 percent in animal models. An early study of patients with other types of cancer is evaluating a small molecule that also appears to block VEGF activity. Neuroscientists believe the molecule may be a simple way to starve glioma tumors and are testing it in animal models.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN